I’m not an information anarchist. I don’t start from the premise that all information must be free. Or even that the availability of content necessitates it being open to all on equal terms. I collect a paycheck and believe others should, too, even if it means foolishly treating digital content as if it were analog property, the way Hollywood continues to do.

But there’s a fundamental problem with today’s digital media policies, and it hit me last night while watching the BBC’s new season of Sherlock.

Yes, I, an American, was watching Sherlock, which premiered last night in the U.K. but doesn’t air in the U.S. on PBS until January 14. The how is not important: anyone with a free U.K. proxy server can watch U.K. content once it airs across the pond. Today I’m focusing on the why: for a show that banks so heavily on surprise, I didn’t want two weeks of my U.K. friends spoiling the show by talking about it.

Put in policy terms, in a world where digital communication moves faster than digital content, we have a serious mismatch, and a significant problem.

Not A Question Of Free

This isn’t a question of whether the BBC has a right to release its content on its terms. It does. U.K. citizens pay for Sherlock and other excellent content to be created through license fees.

When I lived in the U.K., my wife and I lived in terror of the TV detector vans, which allegedly roam the U.K. seeking out people that watch TV without paying. We were guilty, albeit not intentionally. The house we were renting had left a TV for our use, and we innocently turned it on to watch The Muppets, One Man and His Dog(don’t ask me why) and Champions League football. We hadn’t heard about the detector vans until a month or two into our stay and then we were warned that even if we put the TV out in the shed and didn’t use it, the vans would still find us and make us pay.

Big Brother, anyone?

Anyway, the point is that people in the U.K. do pay for Sherlock, albeit not in any targeted sense of someone buying a ticket to see that show or even that channel. When Sherlock airs in the U.S., it will show on PBS, paid for by the government, corporate donations and other donations. While advertising has been introduced in the past two years, PBS is still mostly a public good and doesn’t require that anyone pay for cable or satellite TV.

So even though my British friends pay through a TV tax, I can watch Sherlock completely for free. Yet this still doesn’t make Sherlock “free” for the taking. Whether a matter of legal obligation (one of the BBC’s requirements may be that its content must always have a period of exclusivity in the U.K.) or otherwise, it’s the BBC’s content and it can choose how to distribute it.

It’s A Matter Of Conversation

But the BBC cannot stop how we choose to talk about its programming and therein lies the problem.

We no longer live in a world where it takes months or weeks to travel across national borders, or where communication takes place between two people on either end of an analog phone line. With the explosion of social media, conversations happen across borders in real-time between crowds of people.

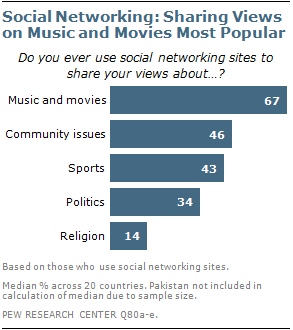

And what do they talk about? Largely movies and music, according to a 2012 Pew Research Center survey (see chart to the right).

Which means, of course, that for the next two weeks every Sherlock fan outside the U.K. must be on red alert for spoilers whenever they get on Twitter, Facebook or other social media. Or it means they need to get a U.K. proxy server and watch Sherlock now.

Two weeks is not big deal, right? “First world problem,” you say. And you’re right. With Downton Abbey, the time delay is six months, but still no one is going to lose sleep over such an issue.

Follow The Money

And yet it should matter greatly to the media companies. Spoiled content turns into unwatched content which turns into less money. Synchronizing content watching with content communication thus becomes a very big deal for both viewers and creators.

Personally, I don’t want information to be free. Not entertainment content, anyway. I want to pay for it. But I don’t want to pay for something that has been spoiled by hearing about it months before I’m able to see it. And for the content creators, they shouldn’t want me to wait, either. It’s not in their financial interest to do so.

Lede image courtesy of the BBC.