Editor’s Note: This was originally published by our partners at Kill Screen.

There’s no question that Ikea is one of the most successful retailers of all time. If you live even remotely close to one of its more than 300 stores, you probably own a Billy or Lack or a Bumerang.

As such, Ikea is a modern marvel of capitalism. The Leiden-based company consumes 1% of the world’s wood supply, has somehow manage to drop prices 2-3% each year, and has made its founder Ingvar Kamprad one of the wealthiest people on the planet. Thus, Ikea is a common template for business schools looking at “the Ikea Way” and its mighty triumvirate of quality, price and speed.

Ikea’s reach extends beyond simple economic heft. In Lauren Collins’ epic 2011 New Yorker profile of the company, she casts the Ikea vision as something that extends beyond pure commerce. “The invisible designer of domestic life, it not only reflects but also molds, in its ubiquity, our routines and our attitudes.” Our Ikea, ourselves, as it were.

For more stories about videogames and culture, follow@killscreen on Twitter.

But to become that successful requires a unique understanding of the consumer mindset and there are certainly many explanations for why this might be. I wanted to introduce something else. Intentionally or not, Ikea embodies some of the best values of good games. I’m not saying that Ikea is a game, per se, but it exhibits many game-like characteristics.

So how?

Designing A Good Maze

Stores like Target or Tesco are just designed with big aisles and malls are just pods of showrooms stuffed together. But Ikea, oh Ikea, has taken a page from any good game designer’s playbook. They make excellent mazes.

As game designer Earnst Adams said of Colossal Cave Adventure in 1998: “A maze should be attractive, clever, and above all, fun to solve. If a maze isn’t interesting or a pleasure to be in, then it’s a bad feature.”

See also: Call Of Duty Doesn’t Understand Grief—But Who Does?

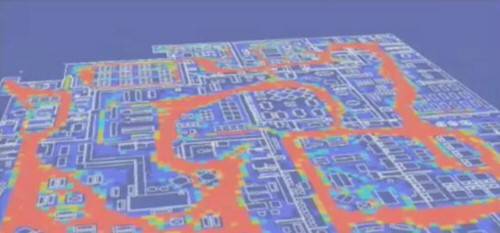

The thing is, it’s easy to make a really hard maze. Just don’t add an exit. But Ikea has made a maze that is designed to keep you in the store long enough to grab a Bumerang, but not long enough to murder your family. In fact, Alan Penn at the University College of London studied the layout of Ikea stores and found that common paths through Ikea resemble a tangled web of seeming chaos but connected but a simple through-route.

He wrote: “Ikea is highly disorienting and yet there is only one route to follow.” This disorientation increases the odds that you’ll grab a Sinnlig on your way out—and, as it turns out, 60% of purchases at Ikea are made unintentionally.

Big games like Skyrim and GTA do something similar. There’s always some person to talk to or side quest to distract you. And though there are many paths in Los Santos, ultimately, Rockstar has you enticed by their universe so you never turn it off. Ikea even has a name for that journey—“the long natural way”—and it’s designed to encourage the customer to see the store in its entirety.

For example, the main aisle of Ikea is supposed to curve every 50 feet or so, to keep the customer interested. A path that is straight for any longer than that is called an Autobahn: big and boring. And if you look at the level design of a contemporary first-person shooter, you’ll find the same thing.

The path is constantly curving to keep you enticed by what lies around the bend. This path through Ikea creates what’s called “organized walking.” And, like any good tutorial, there are no attendants in the showroom, so you have to figure it out yourself.

But the lack of attendants only serves as a ruse; part of the nature of maze design is giving players an illusion of control. “In a maze, the player has absolute control over their position, not considering the constraints imposed by walls,” Cloudberry Kingdom designer Jordan Fisher wrote. But that control at Ikea is only in name only. Yes, you can control your route through the showroom in a sense, but not really.

Architect Bjarke Ingels cut to the heart of the nature of mazes upon reflecting on The BIG Maze which premiered this summer at the National Building Museum in Washington, DC. Mazes inflate the feeling of complexity and belie their simplicity.

“You might only have 10 dead ends or something in the whole maze but you create the illusion of a world that is much bigger than what it actually is,” Ingels says. So, there’s something about getting the maximum bang for your buck that you in a lot within architecture. To distill it down to the absolute necessary but still creating a world of opportunities.”

That’s why the shortcuts through the showroom are so rewarding. That’s the only time where you may actually have control through this deceptively warm and familiar universe.

Build A Story World Through Details

There are other places that use unique retail design to get you to buy stuff. But another big thing Ikea does differently from its competitors is create a story world through language.

Because Ikea’s founder is dyslexic, the company built a whole taxonomy for products to help him remember. Furniture is Swedish place names, chairs are men’s names, and children’s items are mammals and birds. (Lars Petrus’ Ikea dictionary reads like a key to reading Ulysses in this respect.)

See also: Four Things I Learned While Writing A Book About Super Mario Bros. 2

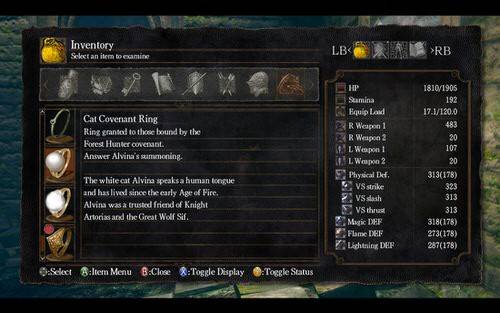

The act of naming an object is an incredibly powerful key to immersion that games use all the time. Think about the names of the drones in BioShock or inventory descriptions in Dark Souls. Each of these games uses unique in-game language to build a convincing story world and keep you there.

For Ikea, they want you to identify with a place, in this case the Swedish concept of “folkhemmet,” a social democratic term coined by the Social Democratic Party leader Per Albin Hansson in 1928, that means “the people’s home.” And this identity is bolstered through numerous elements that want to capture a full-bodied Swedish identity, despite the global presence of the store. The colors are the Swedish national flag; the store sells traditional Swedish foods; the children’s play room is called Smaland as a nod to the founder’s hometown and so on.

As Ursula Lindqvist, an associate professor of Scandinavian studies at Adolphus Gustavus, writes, “The Ikea store is a space of acculturation, a living archive in which values and traits identified as distinctively Swedish are communicated to consumers worldwide through its Nordic-identified product lines, organized walking routes, and nationalistic narrative.”

But the language plays the largest part Ikea builds their retail universe, the same way that Borderlands doesn’t just call a pistol a pistol. It’s a Lacerator or The Dove or the Chiquito Amigo or Athena’s Wisdom. Ikea doesn’t just sell you a coffee table; it sells you a Lack or a Lillbron or a Lovbaken.

As writers Rob Walker and Joshua Glenn said of their Significant Objects project, “It turns out that once you start increasing the emotional energy of inanimate objects, an unpredictable chain reaction is set off.”

Allow Shoppers To Create Their Own Meaning

Ikea engages in what’s called “value co-production.” That means that meaning is co-created with the customers, rather than being embedded in product itself. The biggest way that’s expressed is that you have to build your own stuff. There are economic reasons for this, of course. It’s cheaper to ship deconstructed items. (Ikea’s motto is apparently “We hate air.”)

But the value is that you have to do it yourself, which makes it more meaningful. Researchers found this is at the heart of “the Ikea effect” which suggests that people will value mass-produced items as much as artisan wares … if only they build them piece by frustrating piece. In their 2012 paper, “The Ikea Effect: When Labor Leads to Love,” Michael Norton and his team explain that the reason people love Ikea is a form of “effort justification.” You’ve put so much time into building Lack shelves that it has to be valuable.

See also: Hatsune Miku Is Here To Destroy Everything You Love (And Hate) About Pop Stardom

And it’s exactly the same behavior we find that motivates us to struggle with sadistic shmups like Ikuraga. On the one hand, much like building Kallax shelving units by yourself, it’s almost impossible. On the other hand, we manage to do it. Game makers have a name for that glance too. It’s called flow: “The mental state of operation in which a person performing an activity is fully immersed in a task.” And it occurs in that spot between challenge and skill.

And that’s what Ikea does so well. They balance the economic desire to save money against the odds that you completely throw in the towel and cry in the shower in frustration.

Develop Universal Experiences

This is something we take for granted in games, but think about if you couldn’t play Tetris if you didn’t speak Russian or Super Mario Galaxy if you didn’t speak Japanese. Games are their own language and can be played by anyone, regardless of the nationality, location or background.

Ikea has a similar idea about decorating your home. They call it “democratic design.” As founder Ingvar Kamprad wrote, “Why do the most famous designers always fail to reach the majority of people with their ideas?” So Ikea tries to takes its designs to everyone in the world and designs products that ostensibly could fit in any living room from Shanghai to Berlin or Los Angeles.

This has obviously been a source of critique. Bill Moggridge, the director of the Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum, in New York, calls Ikea’s aesthetic “global functional minimalism.” He says “it’s modernist, and it’s very neutral in order to avoid local preferences.”

Ikea flattens the experience of every home by selling the same furniture which, of course, benefits the company but also benefits the mission of the paradoxical non-profit that technically owns Ikea and is somehow dedicated to furthering the advancement of architecture and interior design.

See also: You Could Make A Great Horror Movie Just By Compiling Cutscenes From Silent Hill 2

Regardless, that impulse for world domination has a pleasant by-product in that creates a common design language for people around the world. It’s the same type of experience that Jenova Chen wanted to make in Journey. Chen argued to me that the language we use is a facade and that games like Journey can be played by anyone. One could argue is the same desire to explains the lack of words on Ikea’s instructions.

This is no slight against Chen, of course, and the impulse to communicate across borders and without the need of words is the same impulse that animates powerful game experiences. And that’s the same for chess and Netrunner and basketball. When designed well, games are exemplars of democratic design the world over.

More From Kill Screen

- The Violent, Lonely Minds Of Grand Theft Auto 5

- Nintendo Has Ripped Open A Transdimensional Wormhole And Nothing Is Safe

- Dragon Age: Inquisition Is All Business

For more stories about videogames and culture, follow@killscreen on Twitter.

Lead image by Gerard Stolk. Day150_time freezes by Ana C. Ikea, Snapshot Taipei, Taiwan by Luke Ma.