You’ve seen it before. Someone raises a bazillion dollars and Twitter lights up with congratulations, as if the ability to raise money is synonymous with success. While it’s true that sometimes venture money does signal something positive is happening at a company, the best indicator of long-term success is a large and growing ecosystem.

In other words, look to developers, the tech industry’s “kingmakers,” to borrow Redmonk’s term.

Something Ventured, Little Gained

Why not venture capitalists? After all, they’re the ones funding tomorrow’s next big Microsoft or Google, right?

Well, no. First of all, none of today’s industry titans started with venture capital. From Facebook to Google to Microsoft to Oracle, each of the industry’s leading technology vendors started with great technology that developers or users loved.

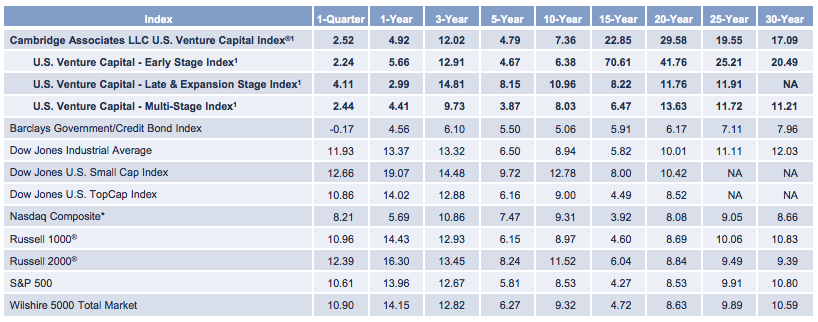

Besides, it’s not as if VCs have much of a track record (Webvan, anyone? Or Color?). While we tend to think of venture capital as a high-risk, high-return gamble on the future of technology, the reality is that venture firms have averaged a measly 7.4% return over the last 10 years, according to Cambridge Associates, which means that VCs delivered worse returns than every major U.S. stock index.

In other words, your money was worth more in an index tracking the S&P 500 this past decade than with a venture firm:

Not every VC, of course. As Businessweek notes, some firms like Greylock have delivered outsized returns for their investors. Even so, as O’Reilly Alpha Tech Ventures co-founder and managing director Bryce Roberts thinks the industry must change to survive:

Not surprisingly, OATV’s investment thesis is to follow the alpha geeks; to see the future by looking at what matters most to the über geeks of today. OATV helped to spark the trend toward smaller funds tailored toward early-stage deals, many of which try to predict where ecosystems will emerge.

The irony, however, is that smart money is rarely as good as smart developers at predicting the future. JBoss, SpringSource and other companies already had vibrant communities before VCs got involved to try to monetize them.

Slavishly Following VCs On Twitter

When not dispensing cash (which is most of the time), VCs are also prone to dispense wisdom via Twitter. There are a few, like GRP Partners’ Mark Suster (@msuster) and Union Square Ventures’ Fred Wilson (@fredwilson), who regularly teach me a great deal about the technology business. Others, like O’Reilly Alpha Tech Venture’s Bryce Roberts (@bryce) and Greylock’s John Lilly (@johnolilly), offer insight into life in general.

But then there are legendary investors like Kleiner Perkins’ John Doerr whose Twitter feed reads like an infomercial for his portfolio companies. Not very interesting or enlightening.

Like venture returns, I suspect the ROI on following the average VC is quite low. While the average Twitter user has just 208 followers, the average VC commands 3,500 followers, according to Zeno Group data. People likely follow the VCs hoping to get a nugget of insight or to make a connection that will generate a nugget of Series A financing.

In my experience, neither is likely.

Average Joes, Average Josephines

Which is not to disparage VCs. Rather, it’s simply to recognize that they, like everyone else, can be average without much to say. And they can be exceptionally brilliant, generous people, just like we find outside the VC world.

But the larger point is that developers, not VCs, are the best indicator of a technology’s success. As Gustavo Niemeyer argues, “Network effects and dependency relationships [are] what make developers a better indicator [of success] than VCs,” because a successful developer ecosystem reinforces and feeds itself. VCs can dump money into a company, but money ultimately is no guarantor of success.

In sum, VCs aren’t members of the Justice League, donning capes and skintight suits (thankfully) as they battle poor returns and gift cash to a benighted underclass. Importantly, they’re also not nearly as good as developers at defining the future of computing.

So if you want to see the future, look to what developers are doing today. Which open-source projects are they embracing? In which partner programs are they enrolling? These are the real indicators of long-term technology success. Not venture money.

Image courtesy of Shutterstock.