Editor’s Note: This was originally published by our partners at Kill Screen as part of Kill Screen’s Year In Ideas series.

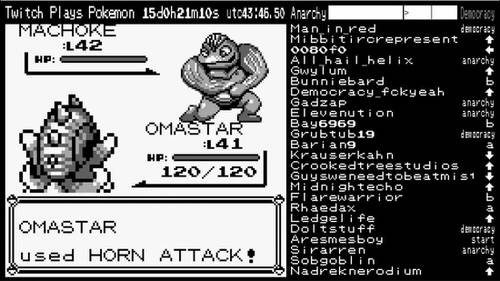

Twitch Plays Pokemon is one of those ideas that should never have really caught on the way it did. Type a command into an endlessly scrolling barrage of Twitch.tv comments, look over at the tiny GameBoy emulator at the left of the screen, and if you’re lucky, you might just see the avatar do what you asked. This was never how things really went down, though.

With thousands of TPPers at their computers fighting to have their commands heard, most inputs would never actually register with the computer. This was the video game equivalent of closing your eyes, making a wish and then throwing your penny into a volcano.

For more stories about video games and culture, follow@killscreen on Twitter.

Still, the offbeat social experiment caught on like gangbusters. The original run lasted two weeks, attracted millions of viewers, and, by its end, had become a bona fide cultural phenomenon.

The problem with Twitch Plays Pokemon is that it was pretty much a one-time deal. The stream is still ongoing, constantly cranking through new Pokemons on a 24/7 basis, but the channel will never again live up to that first run, and there’s no reason why it should. Twitch Plays Pokemon may have been the most impressive crack at “crowd-play” to date (its 2013 predecessor Salty Bet was more of a savage curiosity), the interactive element felt about as exciting as stuffing a million people into a Ford Pinto and making them drive from LA to San Francisco.

It was nice that the Internet had found a way to pat itself on the back, but nobody wanted to spend another day fumbling through Start menus and walking around in circles.

Still, necessity is the mother of invention, and even something as convoluted as Twitch Plays Pokemon can become interesting when it confronts the Internet with a big enough challenge. This was a prime opportunity for creative ingenuity, and after a while the act of observation completely eclipsed the act of play. Viewers became scribes, interpreting the abstract messages of a volatile dot matrix oracle.

For Twitch Plays Pokemon, there was no better place to make direct contact with the chaos than the naming menu, which allows players to nickname the creatures they’ve caught. The Twitch chat scribes would wait anxiously while the cursor flicked through letters like a roulette wheel, only to emerge with some unintelligible moniker along the lines of “ABBBBBBK(” or “JLVWNNOOOO.”

Watching the Twitch chat accelerate in the aftermath of a nicknaming was not unlike gazing into a supernova. When the Twitch roulette eventually landed on the nickname of “AA-j” for its new Zapdos, the cultural arbiters of TPP went to work, searching desperately for meaning in this random message. A few interpretations of the name “AA-j” stuck, but some of them—like “Battery Bird”—felt freakishly apt for an electric-type Pokemon whose name started with double A’s.

This was magic, as if the Internet had convened to paintball a Pollock and inexplicably came back with a Bruegel. What had started as an ambitious exercise in futility became an impromptu oral tradition complete with sad goodbyes, avian messiahs, and one almighty Helix Fossil to reign over them all.

Tiny Cogs In A Fascinating Machine

The world post-TPP became a mosh pit of half-baked attempts to rekindle the magic of that first run. Between Overwolf’s CrowdPlay app, Dead Nation’s Twitch-integrated spectator voting system, and marginally successful TPP spin-offs like Fish Play Street Fighter, it looked for a minute like these oddities could actually catch on as-is.

What all these attempts failed to do—and which Twitch Plays Pokemon could only pull off once—was to embrace the constrictive input system as a grand metaphysical force. Through some form of digital blood-alchemy, viewers found a way to humanize a mode of interaction which, by its nature, had obliterated the impact of individual participants.

One of the earliest forms of crowd art was a surrealist technique called cadavre exquis—“Exquisite Corpse.” An artist would draw out a body part and then conceal the majority of whatever she’d just drawn. From there, she’d pass it on to another artist, who would expand on the original by attaching new body parts of their own. The result was an Exquisite Corpse: A grotesque and deformed mess of flesh and phalanges, with legs jutting out from necks and toenails growing in nostrils.

Any Exquisite Corpse with more than two artists took on the guise of anonymity. While a contributor’s distinct style might betray the occasional limb, most idiosyncrasies would blend into the whole of the cadaver. In this sense, the Exquisite Corpse was a meditation on the unsettling byproducts of artistic and collaborative dissonance.

Twitch Plays Pokemon worked its magic in a similar way. Instead of contributing to some grand vision, participants became tiny cogs in a fascinating machine. By embracing this conceit, TPP became a bizarro reflection on the chaos of the Internet in 2014.

This undermining of the collaborative mechanism flies in the face of most crowd art, which has traditionally sought to incorporate scattered talents into a greater whole. For the performance of his original composition “Lux Aurumque,” Eric Whitacre gathered up a 2,000-person virtual choir, whose members each recorded their vocal parts on webcam.

With the audio and video edited together (a process that must have taken days to perfect) the final product is a haunting work whose tenor takes on an ethereal, almost synthetic quality. As the vocal median approaches an uncanny perfection, the only thing to keep the song grounded is a slight discrepancy in cutoffs, with hundreds of discernible plosives ending each phrase.

Along with projects like Janet Echelman and Aaron Koblin’s interactive sky tapestry Unnumbered Sparks and the irreverent Star Wars Uncut, Whitacre’s virtual choir represents a more human-centric brand of crowd spectacle. If you were to take these works and hone in on one specific part, you’d be able to pick out distinct stylistic voices from within the work itself. Instead of constructing a monolithic culture to surround it, the work creates its own internal style from individual expressions.

Don’t Trust Neanderthals Behind The Controllers

Contrary to what Twitch Plays Pokemon might suggest, it’s the people-centric experiences that will help crowd-play make the biggest splash. Robot Loves Kitty’s weird and ambitious project Upsilon Circuit takes some cues from TPP by allowing spectators to vote on player upgrades, but differs in just about every other regard. As a game show-meets-RPG, a couple participants actually sit behind a controller and play the game, with viewers guiding their path to either assist or sabotage their efforts.

See also: Call Of Duty Doesn’t Understand Grief—But Who Does?

This approach is way more Whitacre than Exquisite Corpse, but brings a ton of problems that Twitch Plays Pokemon never had to worry about. By disempowering individual players, TPP had flipped the script on would-be trolls, making them an essential part of the creative process. Often, the most chaotic inputs would produce the stream’s most memorable and heart-wrenching moments.

But for Upsilon Circuit, which attempts to give every player a tangible sense of control, trolls have more to work with. Instead of letting the chaos unfurl naturally, they end up relying on player cooperation. If Upsilon Circuit is ever going to work out like a game show, it’ll have to find some incentive to keep contestants coming back until they lose.

For the freeware project please be nice 🙁, Aran Koning extrapolated this idea to its natural extreme, putting his tiny development team at the complete mercy of players. As the game’s central mechanic, the first person to beat a new version of please be nice 🙁 gets to recommend a new feature. As part of the deal, Koning and Co. have to develop that feature, bless their hearts.

As of now, please be nice 🙁 is a broken, meme-riddled, lumbering mess of mechanical non-sequiturs, but maybe that’s the point. Maybe please be nice 🙁 is a cautionary tale that we shouldn’t trust the power-hungry neanderthals behind the controllers. At the very least, after more than 100 iterations, the individual footprints that stomped this poor game into the ground have also made it instantly recognizable. There’s nothing else quite like please be nice 🙁 , and some respite in knowing that there probably never will be.

For now, the ideal path for crowd-play seems to take the middle road: Don’t give players too much power, but don’t diminish their impact, either. As of now, progress on this front is a bit of a slow burn. Way ahead of the pack is EVE Online, whose in-game world is almost completely controlled by players, but can only uphold its flexibility by way of a prohibitive learning curve. The rest have tended to lag far behind, using crowd influence—and not crowd-play—to give their worlds a bit of human depth.

By displaying the current progress of other players on the map, Inkle’s interactive adventure game 80 Days enforced the challenge of global circumnavigation as a high-stakes competition. Elsewhere, Hello Games’ upcoming No Man’s Sky lets players explore the universe, tacking their names permanently onto the planets they discover. These are a far cry from crowd-play proper, but with online infrastructures to build and trolls to worry about, the genre will have to crawl before it can sprint.

See also: Four Things I Learned While Writing A Book About Super Mario Bros. 2

Twitch Plays Pokemon’s stroke of genius was to sidestep these technical limitations through its comically arcane input system. By harnessing the Internet’s collective imagination, the stream showcased all the weird, glorious potential of crowd-play even as it proceeded to to make a mockery of the idea itself.

With an Internet-sized dose of creative ingenuity, the stream became both a defining cultural moment of 2014 and an experimental look into the future of the video game medium. It’ll be a long and gradual climb before we establish a crowd-play platform as compelling asTwitch Plays Pokemon; the real challenge will be to make it stick.

More From Kill Screen

- Kill Screen’s Year In Ideas

- We Played Lindsay Lohan’s VideoGame So You Wouldn’t Have To

- We Are Slaves To Destiny

For more stories about video games and culture, follow@killscreen on Twitter.

Lead image by Jordan Rosenberg