Despite the number of popular dystopian novels written over the years, Americans have continually been optimistic when it comes to the future of technology. At least, the distant future of technology. We’re far less sanguine about the technology that threatens to upend our lives today or tomorrow, as a new Pew Research survey suggests.

In 1988, the Los Angeles Times took a break from crushing traffic (no, not really) to anticipate they’d have robotic maids and holographic conference calls in just 25 years. That prediction didn’t come to fruition, but it hasn’t stopped people from dreaming of a distant future where humans can teleport from one place to another, or control the weather, even as we anguish over near-term technological realities of “Glassholes,” inbox overload and more.

Following this trend, Americans are currently bullish on lab-grown organs, computer-generated art and other plausible advances in technology, with 59% expecting that technology will make our lives better.

Why is it that technological advances always look best at a distance?

The Rich And Educated Love Technology’s Future

Especially, that is, if you’re rich, educated and male. Right or wrong, based on Pew’s survey, if you are rich, educated and male, you are more likely to be bullish about technology.

Just 52% of those making under $30,000 feel that technological innovations will make their lives better, while 67% of those making over $75,000 expect those same innovations to improve their lives. In other words, those that make more money tend to feel more optimistic about the future of technology.

For those that have high school degrees and maybe a little college education, 56% of those people see technology improving their lot. That number rises to 66% among those holding a college degree. Perhaps given superior access to technology makes the relatively affluent and educated more bullish on its potential.

Interestingly, while one’s faith in technology tends to correlate with one’s income, it doesn’t correlate with age. Those 65 or older feel roughly the same buoyant feelings about technology’s potential as those under 24, or in between. But if we just look at males with college degrees, suddenly we’re looking at a population in which 79% feel that technological advances will make their lives “mostly better.”

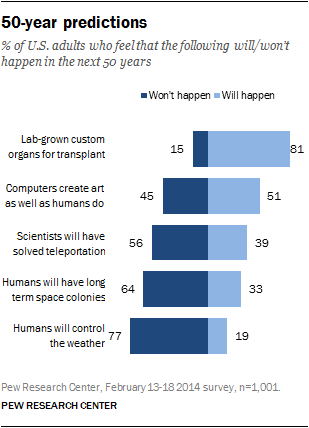

And what does that future look like? Well, given the recent advances in biological engineering, it’s not surprising that we see lab-grown organs as a distinct possibility, even if we can’t quite see a future of “Beam me up, Scotty!” Bizarrely, we seem to be evenly split on whether computers will generate art (novels, paintings, etc.) that rivals what humans produce, with 51% believing this will happen in the next 50 years, while 45% think it will not.

Though apparently Americans already read the sort of drivel that a computer could write. Twilight, anyone?

Not So Bullish On Near-Term Technological Advances

While we seem to be happy about the distant future of technology, we’re ironically much less so about near-term, highly plausible advances. We imagine a future with all the benefits of technology, and none of its downsides.

As Aaron Smith, a senior researcher at Pew and the author of the report, notes:

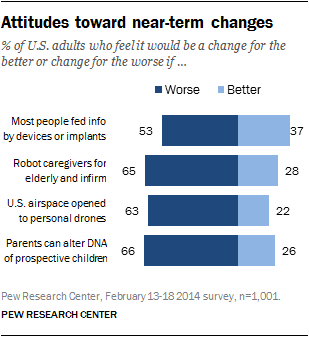

[We] are especially concerned about developments that have the potential to upend long-standing social norms around things like personal privacy, surveillance, and the nature of social relationships.

To wit, roughly half of Americans think it would be a bad thing if “most people wear implants or other devices that constantly show them information about the world around them,” reflecting a distaste for a future filled with Google Glass. On other probable advances, Americans are even less enthusiastic:

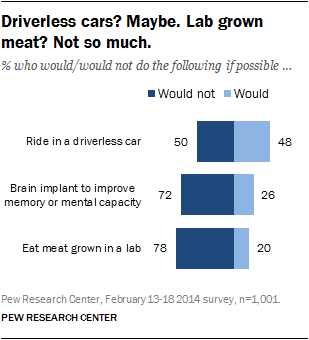

And while Americans may like the idea of a certain technology, the survey suggests they’d prefer someone else try it out first:

In other words, we love technology, but we’re not completely sure if the forthcoming advances are what we actually want.

What is it that we’re looking forward to most? When asked what advancements people would really like to see, the most popular answers included travel improvements like flying cars and bikes, or even personal spacecraft; time travel and health improvements that extend human longevity or cure major diseases.

Given that Google appears most likely to give us self-driving and, perhaps, flying cars—paid for, in part, with our personal data—a conflict is brewing between what we want and what we’ll get.

Why Are We So Bad At Predicting The Future?

That said, we’re pretty poor at predicting the future, anyway. So as much as we want time travel, we’re probably not goign to get it. Not how we expect, anyway. How bad are we at predicting, exactly? Well, Freakonomics co-author Stephen Dubner argues “even experts are only nominally better than a coin flip.” (For those paying attention at home, that’s not very good.)

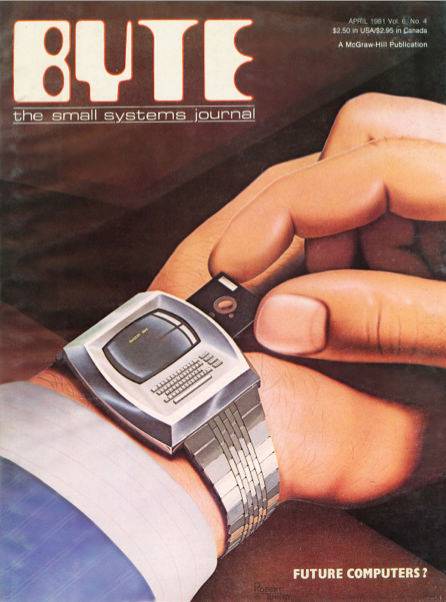

Harry McCracken nails the reason in commenting on this 1981 cover of Byte magazine:

We tend to think that new products will be a lot like the ones we know. We shoehorn existing concepts where they don’t belong. Oftentimes, we don’t dream big enough.

McCracken then goes on to point out the flaws in our current thinking about smartwatches:

Much of the thinking about smartwatches involves devices that look suspiciously like shrunken smartphones. That’s what we know. But I won’t be the least bit surprised if the first transcendently important wearable device of our era–the iPhone of its category–turns out to have only slightly more in common with a 2014 smartphone than it does with a 1981 computer.

In other words, we fail to predict the future because we’re completely constrained by our past.

A Future That Looks Like Her?

Whatever our near-term imaginings, like keyboard-less desktops à la Her, the future will likely not be what we expect. In 1988, the Los Angeles Times predicted a future of robotic dogs and supersonic jets as the norm. While some predictions have been close, most were simply wishful thinking based on the immediate problems of the day.

The one thing that likely will remain true, however, is our enduring ability to see technology fixing all our future problems … despite doing a somewhat dismal job of managing this in the present.

Image courtesy of Shutterstock