Nvidia has just about pulled off the trick of rendering computer-generated human faces — in real time — that won’t make viewers squirm. At least so long as they don’t grimace. Or try to talk.

The graphics chip maker Nvidia said on Tuesday that it had teamed up with the University of Southern California to develop two sets of simulation technologies designed to improve rendering and simulations in video games, one for oceans (Wave Works) and one for faces (Face Works).

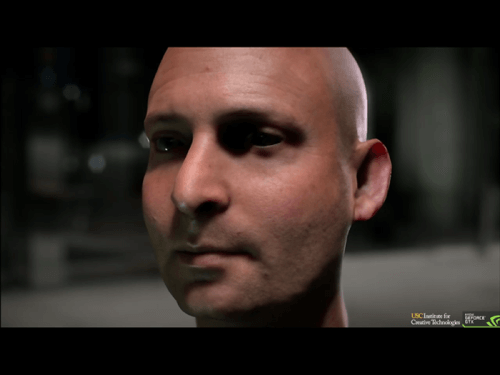

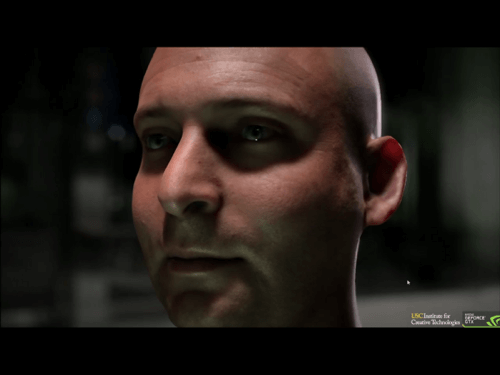

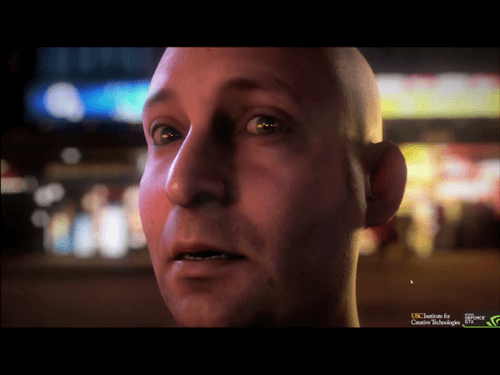

The faces technology is the big deal here. At certain moments during a demonstration at its GPU Technology Conference, Nvidia’s virtual “Ira” transcended the so-called “uncanny valley” and made me think that the virtual head on stage was an actual, living person.

It’s been a long time coming.

Graphics Chips: Not Just For Graphics Any More

Years ago, Nvidia, Rendition, 3Dlabs and others helped transform the PC with the introduction of 3D graphics, from which evolved PC gaming, CAD animation, video production and a number of other creative enterprises. Nvidia’s chief executive Jen-Hsun Huang has been an evangelist of sorts, helping to push Nvidia into the enterprise space with integrated machines that use its graphics processing units (GPUs), as well as into smartphones and tablets with new versions of its Tegra chips.

“Over the last 20 years, this medium has transformed the PC from a computer for information and productivity to one of creativity, expression and discovery,” Huang said in his opening keynote. “The beauty and the power of interactivity this medium allows us to connect with ideas in a way that no other medium can. And the GPU is the engine of this medium.”

The fundamental building block of the GPU is the polygon, also known as “triangles” – groundbreaking games like Alone in the Dark created 3D characters out of polygons that players could easily distinquish. Today, however, faster processors have allowed those 3D polygons to become so small that they can’t seen by the naked eye. Those 3D surfaces can be colored, textured and even “bump-mapped” to break up the regularity of the image, improving realism.

At the same time, GPUs have become physics engines, modelling everything from how light passes through and reflects off of objects – ray tracing – to applying real “physics” to objects as they fall and bounce. Tracking particles as they move, such as smoke or water, is also part of the equation. That’s the kind of computational power that supercomputers tap into – and in February, Nvidia launched its Titan card, using the same GPU technology as the world’s fastest supercomputer, ORNL’s Titan, uses.

Face Works, Ira And The “Uncanny Valley”

For a time, both Nvidia and its chief rival, ATI Technologies (now part of AMD) used, well, virtual dolls, to demonstrate the realism of their graphics technology and appeal to hormone-fueled gamers. AMD’s Ruby is a thing of the past, but Nvidia’s fairy-like Dawn appeared in Huang’s keynote. The showcase for 2002’s GeForce FX line, Dawn was created to embody “cinematic computing” and turned heads with impressive attention to detail, realistic hair and dynamic lighting effects. But Face Works and Ira are the future.

Nvidia’s Face Works was developed in conjunction with USC’s Institute for Creative Technologies, which helped develop LightStage, a high-speed illumination system designed for human-scale subjects consisting of 6,500 white LED sources. Essentially, Huang said, a person marches into a giant sphere, where the subject is photographed from 253 different directions. Each image is matted onto a black background, and compiled into a 3D object. Face Works allows each object to be modified, or “stretched,” to simulate speech and movement.

It’s not easy. “Simulating an ocean is hard; simulating a face is harder,” Huang said.

Humans are trained to instinctively spot things that are a little off, and that reaction, dubbed “the uncanny valley,” ironically kicks in the more realistic a simulation gets. Basically, some people get creeped out by CGI that looks a little too realistic, but not quite realistic enough to be fully convincing.

Ira demonstrates the problem. As these images show, Ira looks quite normal – fully human, actually, under certain lighting conditions. What Face Works does is model light as it enters the skin, reflects, and diffuses through the skin’s surface. Slight disfigurements – a freckle, skin pores – add to the realism.

But the illusion often breaks when the 3D model moves, as you can see in the keynote video below (the ocean modeling begins at about 9 minutes in, Ira and Dawn appear about 16 minutes in). Essentially, Ira looks eerily realistic when motionless, but when he grimaces (and, above all, talks) we begin to pick up on how his facial expressions aren’t quite lifelike.

Still, recent games like L.A. Noire became famous for their realistic depictions of human faces, and “reading” expressions became a gameplay mechanic. Years ago, getting those right at all was an amazing accomplishment. We’re now at the point where companies like Nvidia get it right most of the time. “All of the time,” it seems, will soon be within our grasp.

Wave Works: Splash!

Nvidia’s ocean simulation, meanwhile, uses Wave Works to tap into Titan for what the company called the most realistic ocean simulation ever. Most water simulations paint the ocean as a flat surface, with random ripples distorting it. Objects that “float” on top, like a ship, might not actually move in response to the ocean’s undulations.

Wave Works, however, uses 20,000 “virtual sensors” on a ship model to model water pressure, and to respond to the proximity of the water on the ship. And Water Works even models spray, tracking 100,000 “spray particles” as they move through the air. The Nvidia software can model an entire Beaufort scale of wind speed, dialing up everything from a sunny day to a near-hurricane, Huang said. And as the ship moves, it crashes through the waves, being tossed up and down. This simulation, at least, was completely convincing.