When it comes to video games, the death knell is rung loudly and frequently. In an industry so intrinsically tied to technological innovation, we won’t stop hearing any time soon about what former trend or gaming mainstay has its head on the chopping block. The most recent forecast from worried gaming circles: original, story-driven, triple-A games are too bloated and risky to survive in a cheaper, stripped-down and more mobile world. Unfortunately, there’s a lot of evidence backing this claim up.

Case in point: BioShock Infinite, which hit shelves on March 26 to universal acclaim. An artistic endeavor that cost anywhere between $100 to $200 million (developer Irrational Games won’t confirm) to make and market on top of almost five years of development to fine tune it to near perfection, it’s the second original installment in the BioShock series.

But it’s not a sequel. A game unto itself, it continues the trend of creator and writer Ken Levine’s visions of thought-provoking period pieces. This one happens to mash a 1912 setting with pop-culture aesthetics, sensitive American history (like racism and eugenics) and moral philosophy into what is being called easily one of the greatest games ever made. In other words, while the first BioShock was a coming-of-age moment for video games as an art form back in 2007, Infinite can be viewed as the epitome of the modern, blockbuster “art game,” a term usually reserved for offbeat indie titles but one that aptly fits the murky, morality-infused waters that only BioShock treads.

Despite all the accolades, BioShock Infinite might be the last of its kind. A number of factors are contributing to this outcome, but principally the struggle is between the money that can be made versus the amount of time, effort and studio dollars invested. Early sales reports from the United Kingdom say that despite the fever pitch engulfing the gaming community, BioShock Infinite still didn’t outsell the new Tomb Raider at launch.

The gaming landscape is allowing independent developers to gain recognition easier and faster than ever before, mobile and Facebook games are generating more and more revenue, and a $99 console has Kickstarted its way into the hands of consumers. So there might not be a place for an artistically grand game with a $100 million plus budget, a $60 consumer price tag and a narrower target audience. Well, at least one that doesn’t have a number tagged on the end of its name.

In The Next Console Generation, Sequels Will Sell

Of course, a handful of big-budget, triple-A games are slated for the end of the current generation of consoles this year. And 2014 and 2015 hold the promise of a slew of new games for the PlayStation 4 and Xbox ‘Durango,’ as its called at the moment.

But a lot of these titles – and a healthy chunk of what Sony debuted at its PS4 event in February – were sequels within established franchises that are only confirmed and shown off because publishers know they will sell.

After all, your annual Call of Duty or Assassin’s Creed take an international team of developers only a year to churn out and still make hundreds of millions of dollars in sales (Call of Duty: Black Ops 2 made $500 million in its first day, making it the largest entertainment launch ever).

These games still cost tens of millions of dollars to make, but are offering increasingly less innovation with each iteration so the developers can put them on shelves every fall and keep turning those profits. However, to call BioShock a franchise – and Infinite a sequel – is to ignore its studio Irrational Games’ mission, which is delivering unique, orginal, epic stories that constantly push the medium. Given the rave reviews, the game pulls that off well.

So it’s not quite the case that BioShock Infinite will be the last “art game” as it is likely that it could be the last big-budget one. As the money begins to move away from console games in general, what’s left for triple-A titles will naturally funnel to profitable franchises and not to unique, original gambles like BioShock.

BioShock was such a gamble in fact that Levine, just to get the series off the ground last decade, had to pitch the original for three years before getting a publisher, Take-Two Interactive, to put some money behind it. That kind of attitude will become less and less common as the financial jaws begin to close in on console game publishing.

Follow The Money: Facebook And Mobile

Hardcore gamers scoff at the shallowness of Angry Birds, the manipulative tactics of Facebook games, and the move towards a mobile-dominated industry offering smaller satisfactions. But the sad truth is that that’s where the money is.

Console sales are tanking. NPD Group reported last month that console sales fell 36% in February from the same time last year (though you could attribute some of that to consumers holding out for Sony and Microsoft’s next generation), and Nintendo’s Wii U has been hurting of late. As for game sales, those fell 25%.

(See also: Game Consoles Are Already Dead, And Developers Know It)

Compare that to how Facebook game developers have been doing and you can start to see the shift. Makers of Facebook games like Candy Crush generated a total of $2.8 billion in 2012 alone. These are free games developed with the sole purpose of making you spend more time on Facebook and driving you, through addiction, to pony up more money than any traditional console game could ever milk out of you.

As for mobile games, they generated $2.1 billion last year and will keep growing alongside digitally sold titles and downloadable content. These are the new money makers, typically using a free model that sucks players dry like for instance Real Racing 3, described as “F1 meets Farmville” because of its microtransaction system that forces you to pay every 30 minutes to keep playing.

The final frontier to collapse into the gaming chasm is the indie community, which has undergone a bit of a transformation ever since the big hardware companies gained the ability to sell independently developed titles over their online marketplaces at prices as cheap as $5 and $10.

The robust new market for quirky, well-designed games from small teams raises an interesting question: if indie games can provide a thought-provoking, philosophical and emotional interactive experience, what are we to lose in chopping off the triple-A limb if not simply scale and scope?

The Indie Game Revolution

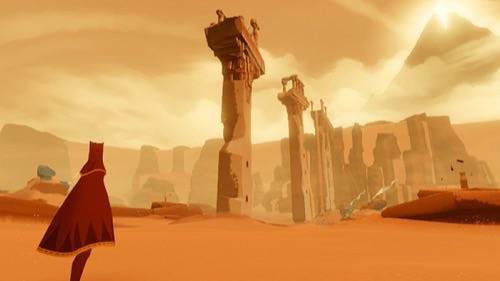

At this year’s Game Developer’s Conference that took place in San Francisco last week, downloadable game Journey became the first independent title to win the Game of the Year award. That would be on top of the game’s other multiple game of the year awards and its Best Soundtrack Grammy nomination, a first for the medium.

Journey has been hailed as one of the greatest, most emotional storytelling experiences in modern gaming, and yet it clocks in at about three hours of playtime and only costs $15 to download to your PS3. The concept is simple: play as an unnamed, cloaked figure that must travel to the peak of mountain. Yet it has a unique mechanism, as most indie games do, that allows you to join up with an anonymous player from anywhere in the world who can serendipitously enter your game at any time.

This kind of thought-provoking take on gaming concepts is part of the canon of “art games,” a genre getting more and more recognition from mainstream markets. These titles are also fulfilling a need for deep, meaningful games in a world where the next BioShock Infinite is looking less and less likely. They’re just doing it on a smaller scale and for less money.

“Like it or not, we’re not the Clash anymore. We’re Green Day,” said Andy Schatz, an indie game designer, in an interview with The New York Times’ Chris Sullentrop. A clever analogy and one that accurately describes the indie game market as it’s evolved from fighting the traditional system to being embraced by it.

This trend bodes well for the future of what was once a peripheral community that could barely get its creations on the market, but is also yet another reason why the industry may not sustain projects as bold and expensive as BioShock in the future.

The Ground Is Shifting

To deny there are artistic, big-budget games on the horizon would be to ignore the work of a handful of forward-thinking studios. Naughty Dog is producing The Last of Us, a post-apocalyptic game that puts you in the role of protecting a young girl amid vicious survival combat, and French studio Quantic Dream is making Beyond Two Souls, the first ever title to use full motion capture to transform an actress (Ellen Page, in this case) into a video game character while keeping real-world likeness completely intact.

These games are doing what BioShock Infinite did: building off a previous success (Naughty Dog with its Uncharted series and Quantic Dream with Heavy Rain) and trying something new and envelope pushing. But in many ways they are also maneuvering the line between a bold step forward for the medium and something that still resembles a marketable blockbuster-style psychological thriller.

BioShock’s appeal comes primarily from the way it feels like a complete realization of artistic vision, one painstakingly crafted over many years fraught with uncertainty, revision and a number of high-profile employee departures. It’s a mix of ideas screaming to be translated into film, but likely will never get there because of how impossible it would be.

“For all I know, I’ll never get to work on another big $60 title – or the equivalent of that. Maybe there will be no economy for that. Who knows?” Levine says to nonfiction author and game critic Tom Bissell in a Grantland interview. “…I’m pretty confident that talented people will be able to work on quality products. I just don’t know exactly how.” Admitting it’s the ‘how’ that’s up in the air is the first step. Figuring out what to do next is the important part.

For those who have their hands on BioShock Infinite, and to the many who may likely pick it up in the near future, savor the game’s moments and all that went into creating its floating city environment and the one-of-a-kind feel it evokes. It could be the last sign of a dying breed.

Image courtesy of Irrational Games; second image courtesy of Google Play; third image courtesy of thatgamecompany.