Smart electrical grids that deliver energy consumption data from the home to a utility company, through software for analysis and back to consumers at home again, are believed to be a new frontier in environmental responsibility, effective public planning and tech innovation.

Green tech writer, Katie Fehrenbacher, has written an important article arguing that utility companies don’t get it, are afraid of the costs, and are thus unlikely to offer the kind of “real time” data delivery that could serve as a foundation for eye-opening innovation like we’ve seen from the networked world of the Internet.

This Spring at the 5th anniversary of the Web 2.0 Conference, paradigm forefather Tim O’Reilly identified smart utility grids as one of five technologies that could point into the future, past what’s called Web 2.0. As a reporter working in the green tech field every day, Fehrenbacher’s pessimistic forecast for innovation in smart girds is an important read. Can utility companies get it together to help build a future that’s fundamentally innovative?

Fehrenbacher’s article last week, titled Why the Smart Grid Won’t Have the Innovations of the Internet Any Time Soon, began like this:

Many people (myself included) have painted a picture of how the consumer piece of the smart grid could develop into a real-time, two-way communication network that looks a lot like the Internet. In that world, consumers would be able to see variable pricing change in real time, while smart meters and energy management devices read and visualize energy consumption data every second, leading to changes in consumer behavior. The ultimate vision of that landscape is that real-time energy data unleashes innovations and applications that we haven’t yet thought of, which will deliver substantial behavior changes.

Well, that’s the outcome for which entrepreneurs and innovators are hoping. The reality is that the consumer piece of the smart grid will look very different for many years to come.

Fehrenbacher goes on to detail the state of the art in smart grids, reporting that private tech firms, including Google, are frustrated with utility company delays of up to 24 hours in eventual return of consumption data to consumers. She draws a comparison with real time GIS location data, which telecom companies initially objected was too expensive to deliver and not really needed by consumers. When the killer app of turn-by-turn driving directions was invented, that debate was put to rest and the real time geolocation data infrastructure was born.

Some of the applications built on real time utility data will serve consumers, others will analyze data in aggregate and serve policy and other decision makers. Tim O’Reilly has invested in a company called AMEE, for example, that has discovered that the energy fluctuations of home appliances are so unique that they can tell what make and model of refrigerator you have by the way it acts when the motor turns on. Then it can suggest a more energy efficient appliance.

Remember how Net Neutrality proponents argue that if internet companies don’t give cheap, equal bandwidth access to small innovators, then the team of people in a garage working on the next YouTube won’t be able to afford to get it out the door? In this case the innovators coming up with the next killer app built on real time utility data won’t be able to bring a service to market because utilities are simply unwilling to invest in making the real time data available to build on. (Fehrenbacher also points out that when it comes to data for analysis beyond consumer use, there are also some security concerns to consider. Not all data should be made available, she says.)

What’s the killer app for smart utility grids? Fehrenbacher says she doesn’t know and that’s the point – we can’t even imagine what kinds of cool and useful applications will be developed on that platform once it’s available. The lack of a killer app leads to less support for the building of the platform, though, a catch-22 we can relate to from discussions of our calls to open up aggregate activity data from social networks for analysis.

We’ve written about three possible models of value for the real time web and we suspect some of the same principles could apply in delivery of real time utility data: ambient awareness, automated actions and monitoring for emerging trends. Those concepts almost make more sense in power than they do on the web.

We followed up with Fehrenbacher and asked her how the real time GIS killer apps got built if there wasn’t an enabling platform, driven by demand for killer apps, yet. This is what she said.

“It was mandated that phone companies have to have location in phones to find 911 callers. So some companies did it by GPS and some did it by triangulation and some services had real time and some didn’t. And then the phone companies wanted to recoup the investment they had to make for 911 location. The companies that had real time location found that they could better recoup the investment with the killer app of real time driving. The other phone companies that didn’t have that, I think eventually added that on, but were late and didn’t recoup investment as fast…It’s [similar] with smart grids, because [those companies and utilities] have to make these investments too, by both upcoming regulation and current regulation, so why not build it out fully so they can create something where they can get more value? But they’re not thinking about it as a platform – they’re thinking about it as controlling the current electric system.”

For more discussion of how smart grids may or may not soon become a platform enabling web-like innovation, see Fehrenbacher’s full post at Earth2Tech.

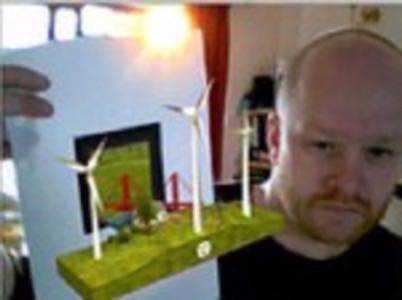

Illustration at top of page: Smart Grid technology in my living room, from GE’s Smart Grid Augmented Reality campaign.