There may or may not be robots that are truly “good” someday, but there will probably be bad robots, if there aren’t already. If not bad robots, then bad robot situations. You can catch a taste of the feeling of what might go wrong in the robot pricing wars that elevate the cost of certain used books on Amazon into millions of dollars.

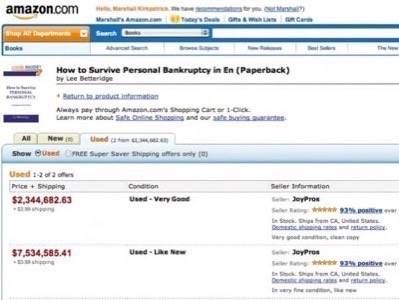

For example, you can’t buy a used copy of Lee Betteridge’s book “How to Survive Personal Bankruptcy” on Amazon today for less than $2.3 million. (Unless you buy it on Kindle! It’s only $7 there.) It’s not just that ironic title, either. Last Spring, a scientific text titled “The Making of a Fly” (about fruit-flies) was found selling for $23m on Amazon. This is amusing, but there’s something deeper and potentially disturbing going on under the surface. It’s an issue of the relationship between human beings and robots.

If there’s ever a time when it’s ok to gaze at the meta navel, I think it’s when considering the unfolding relationship between humanity and the technology we build to serve ourselves.

I was testing the new version of the semantically intelligent social stream reading application Bottlenose this week (RWW’s review) and I really like the content recommendations it offers. (And the custom filtering is incredible!) There’s a stream of individual messages that are suggested for you by Bottlenose that look quite good. One of mine today was a Tweet about a used book on Amazon caught in a bidding war between bots and now priced at millions of dollars.

Above: If you want “Like New” – you’re going to have to pay dearly for it!

The tweet was a link directly to the auction, not to a news article about it. I searched for mentions of Amazon and bots in recent tweets and found a related article, but it looked like no one had written about this phenomenon yet.

So I asked my virtual assistants at Fancyhands if anyone else had written about this before, because I needed to go meet my wife for dinner and didn’t want to take the time to search around myself. Before I left, I fired off emails to a number of people who work in Artificial Intelligence, asking for their comment on the phenomenon.

It turns out that UC Berkley evolutionary biologist Michael Eisen found out about this and wrote a very compelling analysis about why he thinks this is happening, last Spring. CNN’s John D. Sutter found Eisen’s blog post and kicked-off a chain reaction of media coverage. That’s what the person on the other end of the virtual assistant task allocation algorithm at Fancyhands found out and emailed me about, anyway.

Eisen’s belief is that the book sellers operating on Amazon are running low-quality pricing algorithms that are getting caught in an escalating loop. Effectively, one bookseller is running an algorithm that says, “if we’ve got a book and someone else is selling it on Amazon too, change the price to be just under whatever they are charging.” Then the other bookseller is running an algorithm that says “if someone else is selling a book on Amazon, let’s say we’re selling it too, just at a slightly higher price. Then if someone buys it from us, we’ll go buy it from the original seller, resell it to our customer and pocket the profit.”

In the case today of the stay out of bankrupcy book, somehow it’s the same seller making two offers of the same book. One offer seeks to leave a minimum of money on the table but always undercut the other offer, the other offer seeks to arbitrage price discrepencies by offering a book the offer-maker doesn’t posses. It’s a crazy situation.

I asked Neal Richter, an expert on machine learning and the Chief Scientist at the Rubicon Project, a leading real time online ad buying technology provider, how he thought this could happen and what it meant.

“The APIs available for adding and removing inventory from a site like Amazon, plus the transparent pricing, means that anyone with minimal skill can trade on any price discrepancies between marketplaces,” Richter said by email.

“It looks like the flaw in Mr. Eisen’s example was due to the software writers not imposing any limits on their pricing.

“Amazon and other retailers need to have a tax or API fee on some kinds of function calls. If they were to charge $0.05 for every change to a unit of inventory it would setup incentives to better QA the software.

“The expansion of API usage in marketplaces means:

Version 1) Any PhD with an idea can create a startup to add value to a marketplace.

Version 2) Any idiot with an questionable algorithm can screw things up for everyone.

“Failure to account for boundary conditions will screw up a good model in a hurry.”

That’s an interesting solution, and it may be the best way to solve this particular manifestiation of the problem of bots gone wild, but it’s not the only option, either.

Artificial Intelligence technology provider Next IT powers chatterbot services for customers like Alaska Airlines and the US Army. Next IT CTO Charles Wooters says that the fundamental strategy his company employs when it puts artificial intelligence together with big data (millions of real-time customer service queries) is to focus the machines on making it easier for humans to catch errors.

“We can compare what our statistical systems think should have happened with what actually happened, then find high frequency errors,” he explained. “Those benchmark systems aren’t always smarter, but we apply the rule based benchmarks vs the statistical realities – then we always have humans in the loop. We help humans get to the answers that are wrong, quickly. We intelligently sort queues so humans can quickly go through and fix errors.”

That’s how Next IT describes its relationship with Big Data and I think it’s pretty interesting.

Several people I talked to said that what we can see in the Amazon bot pricing battles isn’t really a problem, until this kind of dynamic plays out in real-world financial markets. Presumably something similar could throw a real Stuxnet-style wrench in industrial systems, too.

We do live in a world where a bot can recommend that I read what a person said about bots gone out of control selling an author’s book, where I can find all the best writing about the phenomenon with the help of a virtual assistant on the other end of a queueing mechanism and where other bot-masters can tisk-tisk such a lack of self-control and offer better examples of bots focused on helping humans discover botly errors.

That’s where we’re at – let’s hope nothing goes too wrong!

Crazy robot attack image by Sean McMenemy