What makes some technology so compelling and transformational that it thrives in a school setting and others languish? We’ve all heard stories of computers gathering dust in storage rooms while students and teachers everywhere have taken to photocopiers, calculators and, of course, cell phones.

One of my most surprising moments upon entering a very basic primary school in rural Ayenhyah, Ghana – a room with no electricity or running water – was being told that the school had a no cell-phone policy. Students have such a hunger for communication that they get their hands on a mobile phone by any means necessary. They keep them charged using the full power of their creativity, hooking them up to the small solar cell powering the community’s medical clinic or latching them onto a motorcycle battery. Kids from Botswana to the U.S. to Zambia love to text.

So what tips the technology scales? I think the answer might have something to do with the idea of simple machines – basic building-blocks of technology that help us construct the world around us.

David Risher is the President and co-founder of Worldreader, whose mission is to bring books to all in the developing world. Previously, he was an executive at Amazon.com and Microsoft. He is Twitter at DavidRisherWR.

Simple Machines

I’ve been thinking about simple machines a lot recently, while in Africa working in education. You probably remember simple machines from elementary school science. They’re the basic building blocks of mechanical technology, from the inclined plane that helps move equipment easily from one height to another, to the pulley that enables everything from hoists to the modern bicycle, to the wheel. Simple machines are technology at its most elemental form. Think of a bike climbing a hill and you can see all of them working together gracefully; imagine a dump truck and you see how they allow us to create the tallest buildings and the longest highways. Without them, we’d still be carrying water in pails.

Technology helps us advance, but in education it has often been a source of false hope, peddled by people who promise to revolutionize learning. The problem often is that the technology ignores the basic configuration of any classroom in any school: the triangle that connects students, teachers, and ideas. My experience is that technologies that reinforce the relationship between those three poles represent opportunities for stronger classrooms and better education. But those that interrupt that relationship stall and ultimately fail.

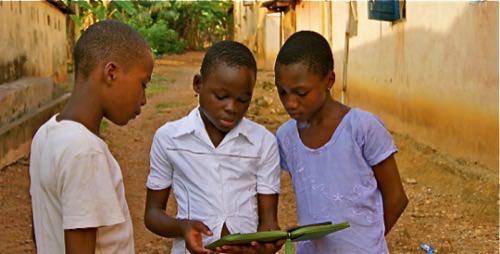

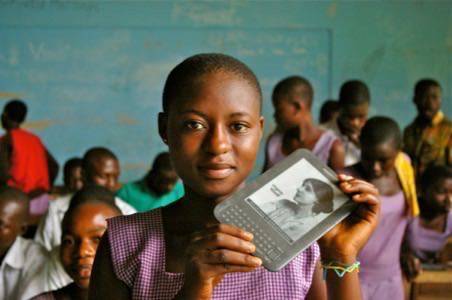

E-readers are a fascinating example of a technology seems to be working in the developing world. At a very basic level, having an e-reader is equivalent to having a set of books at hand. Happily, even in schools with only the most rudimentary learning tools available, both teachers and students are well-versed in the importance of books and the ideas within, and readily recognize the value of having great access to them. This represents an enormous improvement over the status quo, where access to books is extremely limited: Botswana, a country the size of France, has fewer than 10 bookstores, and the village library of Kade, Ghana, is nearly empty of books. Imagine for a moment the power represented by e-readers: Students can walk around holding a library of books larger than all those in the bookstores and libraries of their country. It’s a device that is bigger on the inside than on the outside, like Dr. Who’s Tardis or Harry Potter’s charmed tent.

The e-reader satisfies an important core need, providing access to the books of the world at a moment’s notice. And it does so in a way that’s accessible to both students and teachers, strengthening the bonds between them rather than disrupting their relationship.

The Price Point of Literacy

E-readers have something else going for them as well that is critical in an educational setting: A declining cost, even as the amount of content available increases. Numerous organizations are quickly digitizing the world’s books, including local textbooks and storybooks. There is an enormous and growing variety of books available inexpensively or for free, from open-source textbooks like those from the CK-12 Foundation to public domain classics like the works of Jonathan Swift or Miguel de Cervantes. Meanwhile, the devices themselves are relatively sturdy, work well outside, and their costs are declining almost daily. (Their singleness of purpose also helps: it’s very hard for a teacher to compete with the pull of Facebook or the call of Twitter.)

Perhaps most of all, e-books in the developing world are an example of leverage, a word inspired by another simple machine. Cell phones have paved the way for book and other content delivery as well as for recharging, not to mention helping million of children learn how to take care of and use a small device with a keyboard and screen. Publishers are going digital fast: Amazon has famously reported that it now sells more Kindle books than paper books, and 75% of John Grisham’s newest thriller are sold as e-books.

The cost to donate e-books to the developing world is essentially zero, and might even represent a way to create a new market of readers in a generation. The early results we have seen using e-readers in Kenya and Ghana are very promising, with children spending up to 50% more time reading than before the introduction of e-readers, and reading fluency scores increasing quickly. But what’s most exciting is that the children and teachers are using e-readers even when not being asked to, downloading books and samples and coming to voluntary summer reading programs to have access to the e-books. When books are scarce, access becomes enormously attractive.

This, then, may be a model for use of technology in education: Find or develop technology that allows us to strengthen the basic triangle between teacher, student, and ideas. The example of e-readers can provide valuable clues for how technologies can successfully help education, and in the process, help millions of children get access to books throughout the world.