There was an interesting article recently in The Wall Street Journal by Isacc Arnsdorf that discussed how art gallery and museum patrons are studied as they move through art exhibits. The objective is simple: measure how people navigate through and engage with the art. When I read the article, I immediately thought of some of the things that we’re doing at MindTouch, but really there’s a broader lesson to be learned here.

As co-founder and CEO of MindTouch, Aaron has grown a small open source project into one of the world’s most widely used and successful collaboration platforms. Prior to co-founding MindTouch, Aaron was a member of Microsoft’s Advanced Strategies and Policies division and worked on distributed systems research.

A well-curated art show is not just a bunch of paintings in a room. Items are grouped together to evoke certain ideas. The placards next to artworks that give context details about the author, the era, the method of composition educate the viewer and in doing so make the exhibit more enjoyable. The online documentation offered by a company to its users works the same way in relation to the company’s products or services.

This curation results in a more interactive, useful, and engaging documentation resource. This process goes beyond simply counting page views.

If a museum is lucky enough to have a Picasso on display, the name alone probably makes it a destination piece. Users of all art-appreciation levels will want to pay it a visit. Picasso in that sense is a great common denominator across audiences. And like a Picasso, there is probably a set of documentation that product users flock to first, such as tutorials, FAQs, and feature pages. As the WSJ article shows, to get the full value of having a Picasso on exhibit, you must learn the best ways for your audience to find and view your content.

Just as curators want to help audiences appreciate and understand artwork other than their Picasso, documentation creators want their audiences to understand where and how to find information beyond those first, most popular pages.

Are You Learning From Your Users?

Observing your patrons is only half the exercise. Both museum and content curators must take the information their given and turn that into action. An excerpt from the article explains this well:

Based on what they see, the museums may rearrange art or rewrite the exhibit notes. Their efforts reflect the broader change in the mission of museums: it’s no longer enough to hang artfully curated works. Museum exhibits are expected to be interactive and engaging.

This is exactly what good documentation is about learning from your users, taking their feedback and making decisions on what areas of documentation need to be updated, improved or perhaps removed altogether. This curation results in a more interactive, useful, and engaging documentation resource. This process goes beyond simply counting page views.

Do you know what your users are searching for? And when they search, do you know what they find, or more importantly, don’t find? If your patrons are continually asking for a Monet and not finding one, they’re going to go to another museum.

The same is true for what users are searching for online. Repeatedly seeing Monet in the list of performed searches – with no resulting content – is an indicator of an unmet customer need.

A Virtual Suggestion Box at Each Painting

Back to those exhibit notes. Data from the museum observation showed an interesting trend even for works by famous painters: only 1/4 of the exhibit notes were read. What did they learn from that?

A big problem that the Detroit museum hopes it has solved: getting visitors to read the written descriptions and analysis next to the art. In its pre-renovation studies, it found that the most-read text, between a Matisse and a Picasso, was read by just 26% of visitors. Four panels were read by just 2% of visitors.

So the museum cut the write-up’s lengths to 150 words maximum from 250 to make them appear less intimidating. Curators also broke up blocks of text with bullet points, subheadings, color and graphics.

This is a great example of learning from your users. In this instance it was gleaned from visually tracking visitors. This is not unlike community scoring that you see online for product reviews, or ranking articles on a blog or news site. This capability effectively provides a mini suggestion box at each page users can rate it thumbs up or thumbs down, along with giving suggestions for improvement.

It’s interesting to me that this approach has been replicated offline, in a seemingly unlikely place. Whether you’re curating a museum or designing a new technology, your customers will never do exactly what you predict which is why monitoring their behavior can teach you so much about your product.

In this case the offline world is in many ways learning a lesson from the techniques of the online world. But it’s worth noting that this is a business issue that applies to startups and businesses of all types. Listening to your customers, and doing so in smart, sophisticated ways gives you a competitive advantage, and there’s no way around that whether you’re the newest Twitter client or a local bed and breakfast.

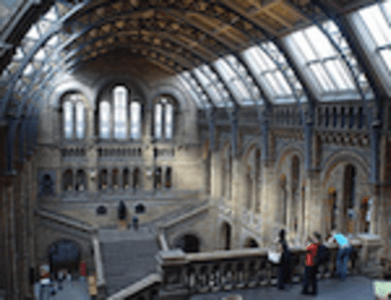

Photo by srboisvert