Consumers screamed for it. Verizon answered. Later this month, the U.S. cellular carrier will offer shared data plans for entire families. Instead of each device on an account being allotted its own data limit, all devices in a family plan will draw from the same data pool. Verizon boasts that it listened to consumers and responded with an innovative service. But when it comes to the bottom line, is Verizon doing American families any favors?

Our Family of Four

ReadWriteWeb discussed the feasibility of shared data plans last year. Let’s bring back our theoretical family of four and apply the shared data rates Verizon announced today.

This theoretical upper-middle-class family has a mother, a father and two children. Both Ma and Pa have a smartphone and a tablet. The teenage kids each have a smartphone and share a tablet between them. The total is seven devices that under the old system would have required seven different data plans.

Cost: $299.97 on the middle tier of Verizon’s current family plan (AT&T, Sprint and T-Mobile rates are slightly different):

- four lines with 700 talk minutes: $119.97

- four smartphones with 2GB monthly data: $120

- three tablets with 1GB monthly data: $60

Note: Cost estimates are before taxes and fees attached by the carriers and individual states.

Focusing on the data aspect of the current family plan, that is 11GB of data for $180. Verizon points out that with the new shared plan, you pay a lot less for the data. The problem? You pay more per device.

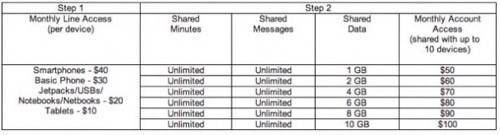

This is the pricing chart that Verizon announced today.

Let’s run the numbers for our theoretical family.

- four smartphones with unlimited minutes: $160

- three tablets: $30

- 10GB monthly shared data plan: $100

In aggregate, the shared data plan comes in at $290, about $10 less than the current Verizon family plan. The family also loses 1GB of data. If we add it back as an overage charge (where the family exceeds its monthly allotment and is charged $10 for every additional GB), then the plans are exactly the same.

Does this surprise anyone? Verizon’s new plan does not give families a discount. The difference amounts to an administrative change in how Verizon gauges use within a family plan, not a change in how much it charges or the revenue it generates.

Convenience and Choice

Let’s go back to our theoretical family. Last fall, we imagined that the father was a low-volume data user (to Dad, the smartphone is really just a phone) while the mother traveled a lot and was a high-volume user. Mom streams movies from Netflix, catches up on shows with Hulu Plus and listens to a lot of Pandora and talk radio with Stitcher. She just loves everything these mobile devices can do and hardly gives a thought to the amount of data she uses. The teenage kids take a lot of pictures, text and use social networks. They watch the occasional movie and a lot of YouTube. All in all, the kids are fairly normal smartphone users.

Without a shared data plan, Dad’s allotment of data pretty much goes to waste. Activities like checking and sending email on your phone take up very little data. The family is punished financially for Mom’s freewheeling ways. So, if we break it down, the family on the shared data plan is actually being far more efficient with their allotment than each individual would be on their own.

This has several benefits for both the consumer and the carrier. Individual consumers, on average, use about 2.2GB of data a month on their smartphones. Under many contracts, such as AT&T’s 3GB for $30, they are paying for data they do not use. In the new Verizon system, those users would be punished for going over their 2GB allowance.

For the carrier, the shared data plan represents a change in how consumers are measured. In the old family plan, a company like Verizon would measure average revenue per user (ARPU). In the shared data plan scenario, the measurement structure changes. The family, instead of being measured as a group of individuals, becomes a unit. When an individual uses more data in a given month, the ARPU for that person goes down. When taken as a unit, an individual’s excess data use gets rolled into a lump sum without damaging (or theoretically, enhancing) Verizon’s ARPU.

Think of your family and ask yourself: What is easier? Is it better to collect family members under one lump-sum plan or keep them partitioned to their own personal data limits? That is really what it comes down to. Verizon is going to make the same amount of money either way. Let us know in the comments what approach your family is going to take.