It’s the schools that give each student an iPad tend to make headlines nowadays. No doubt, more schools are investigating tablets – Apple or otherwise – as part of their one-to-one computing initiatives, looking to replace not just desktop PCs but to replace laptops and netbooks as well. Despite the buzz about iPads, Chromebooks, and the like, one laptop (or tablet) per child is still far from a reality in most schools. And while the iPad is dominating the tablet market among consumers, it’s hardly the most popular, the only or even the best option for schools which are considering mobile device implementations.

That being said, the education technology market is booming, and many schools are seeing the value in equipping their students with their own personal computing devices.

I’ve had the opportunity to test-drive two of the student-oriented PCs on the market – the Intel-powered Classmate PC and Google’s Chromebook – for the past few weeks. In lieu of a traditional “under the hood” review, where I just compare the specs (we don’t review hardware often here at ReadWriteWeb), I want to address some of the larger questions at stake schools will weigh when considering which, if any, of these devices they’ll adopt for one-to-one programs.

The Hardware Doesn’t Matter… Except When It Does

Arguably the most important thing to recognize when it comes to netbooks or tablets or laptops or any technology in the classroom is that the technology itself isn’t some silver bullet that magically modernizes teaching and learning. Putting a personal computer in the hands of each student does give that student access to computing power and (hopefully) to the Internet. But the PC itself doesn’t necessarily change or improve instruction. That needs to change as well, whether students have iPads, Chromebooks, Classmate PCs, or cellphones, otherwise these devices are simply just a very expensive upgrade to the old pen-and-paper, where the students take notes while the teacher lectures at the front of the classroom.

It’s not the device itself that matters, it’s how you use it.

Except when you’re handing out devices to students, particularly K-12 students, the hardware does matter. It has to be durable. It has to reliable. It has to be affordable. It has to work.

If that sounds like the promise of the One Laptop Per Child movement – designing a low-cost computer that could be used by kids in any environment – then the Classmate PC will look like a familiar device. In terms of hardware then, the Classmate PC seems well-suited for younger students in particular. Its exterior is rubberized. It has rounded corners and a handle. It has a water-resistant keyboard and screen. It’s designed to survive bumps and scratches and even drops (from a height of up to 19″).

The Classmate PC also has a rotatable screen, allowing the device to be used more like a tablet – either with or without a stylus.

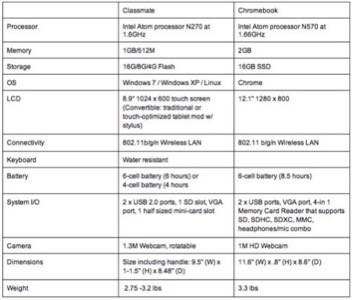

While those elements do set the Classmate PC apart from its netbook cousin Chromebook, the two devices share a lot of similarities when it comes to the rest of what’s under the hood: fairly similar cameras, memory, storage, and processor speeds, for example. Some of the early reviews of the Chromebook have pointed out that the device feels underpowered, and no doubt power-users in the under-18 set would be quick to reach their limitations with either of these devices. But as netbooks, both of these options perform adequately and will likely meet the needs of most students.

Operating Systems, Software, and The Web

The Classmate PCs are loaded with various educational software titles, and some of the big names in educational publishing – Lego, McGraw-Hill, for example – are partners in the endeavor. The Classmate PC also has a Classroom Management and Collaboration Application Suite that allows the computers in a classroom to be networked so that students can easily view their teacher’s screen, for example, or work with one another.

That all feels very standard when it comes to a school- and student-focused piece of equipment. The Chromebook, when it comes to both the OS and the software, feels quite different. It is, as Google points out, “nothing but Web,” and while that does open a lot of possibilities for taking advantage of online resources from traditional and non-traditional academic sources, it’s going to be a big leap for many schools.

Of course, for those that already utilize Google Apps for Education, the Chromebooks make a lot of sense. That same ease by which student accounts (access to Gmail, Docs, and the like) can be managed is now extended to their devices. Updating and upgrading will be far easier for administrators; no longer will every computer have to be rounded up in order to have new software installed.

But just as the Web-based system can be greatly liberatory here, the requirement that students have Internet access for a Chromebook could pose a problem, particularly for those without Internet connections at home. Google does say it plans to roll out support for offline Gmail and Google Docs over the summer, which seems like a baseline requirement for making Chromebooks viable.

And there are still many tools that students and teachers utilize that don’t yet have a Web app. Take Skype, for example, which has seen great adoption by teachers for linking their classrooms with others. Or take Google’s own popular Google Earth or Sketchup tools, neither of which can, as of yet, work in the Chrome OS.

These are the sorts of details that make the Chromebook feel not-quite-ready for primetime. But for schools that are weighing one-to-one laptop programs, there are really no perfect tools yet, as costs (for hardware, software, and IT support) still make the idea largely prohibitive for most schools.

Google has a lot of things right here: a Web-based, rental program, for example. Of course, the Classmate does too, as an heir to the idea of cheap and durable laptops of the One Laptop per Child movement (but, at the end of the day, still quite an expensive piece of equipment).

Looking at these two netbooks side-by-side, it’s clear that the costs of putting computers in every child’s hands is still quite an expensive proposition. But of course, the costs of not doing so are high as well.