Last week’s release of Paper for iPad was a huge boon to the cottage industry of third-party iPad styluses. It was hardly the first app for drawing or writing directly on the screen of an iOS device, but it struck a chord. It was just the right blend of skeuomorphic real-world design and familiar iOS gestures. I had never even considered a stylus before, but this seemed like my chance.

I travel the Internet in fairly Apple-obsessed early-adopter circles, so I went with the stylus I’d seen recommended most often: the Cosmonaut by Studio Neat. Studio Neat made the Glif camera mount, one of the most celebrated iPhone peripherals around, so it seemed like a safe bet.

The Cosmonaut arrived in short order in spartan, Space Race packaging. It’s fairly wide to hold like a pen. It’s black, grippy and dense, the exact same length as an iPhone. The business end exhibits the capacitive properties the touch screen requires: a soft touch that gives way gradually to pressure, just like a fingertip, but more precise.

I quickly found to my surprise that the stylus is a satisfying cursor for normal iOS activity. Launching apps, tapping around, pull-to-refresh, all the usual finger gestures felt pleasantly precise and snappy with the stylus. That’s not its intended use, of course, but it’s an enjoyable way to change up one’s routine.

Unfortunately, it got frustrating as I tried to use the stylus for its real purpose. I am no gifted draftsman, but I found the stylus rather blunt and imprecise in my drawing forays using Paper. There’s no question it was more accurate than the finger. Drawing with a finger on a glass screen feels clumsy and dully painful. But the stylus didn’t feel like much of anything.

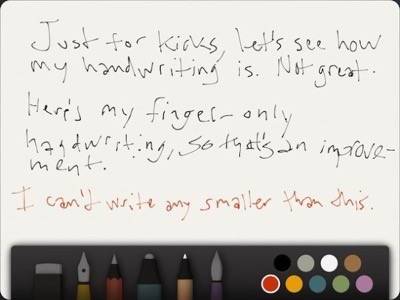

Since writing is my actual trade, I decided to give handwriting a shot. I was not thrilled with the results. It’s very difficult to write small enough using this stylus, but perhaps the wide grip is the problem. There may be better styluses for writing on the iPad, and I’d happily take recommendations.

The Cosmonaut was still vastly better than writing with the tip of my index finger.

“If you see a stylus, they blew it,” Steve Jobs once said. Surely that wasn’t meant to demean Apple’s Newton, a misunderstood but beloved device that paved the way for iOS devices. But after iOS, it was a different world. Apple’s second mobile operating system nearly eliminated the friction between the software and the physical human interacting with it. It felt like touching and manipulating the actual pixels. A stylus would just be an inert barrier in between.

I did feel this barrier in my experiments, but I wouldn’t say it’s the fault of the stylus. My biggest takeaway from the experience is that the iPad itself is the clumsier interface. A stylus is one of the first tools humans ever invented. We have thousands of years of honed experience writing and drawing this way. We feel it with remarkable precision. It’s the capacitive glass screen that’s the inert barrier.

Writing and drawing depend on physical feedback, and the glass provides none. The abstraction is there when we touch the iPad with our fingers, too. There’s no feedback at all, so the software creates illusions of feedback with sounds and images. Those are less compelling with a stylus rather than hands directly on the glass. But don’t blame the stylus. A flat slate of glass is not a tactile work environment. It’s great for abstract work, but not for real handiwork.

Not yet, anyway. It’s too bad those haptic touch feedback rumors didn’t pan out for the new iPad. But we know Apple’s already thinking about the evolution of the computer as a tool in the hand.

Still, even the most tech-savvy people have to admit it when things work better the old-fashioned way.