“Out of the crooked timber of humanity, no straight thing was ever made.” – Immanuel Kant

Ours is an imperfect society. The nature of our reality, our desires and our need to possess, while maintaining a façade of moral righteousness, puts us at odds with the reality that exists within the systems we have created.

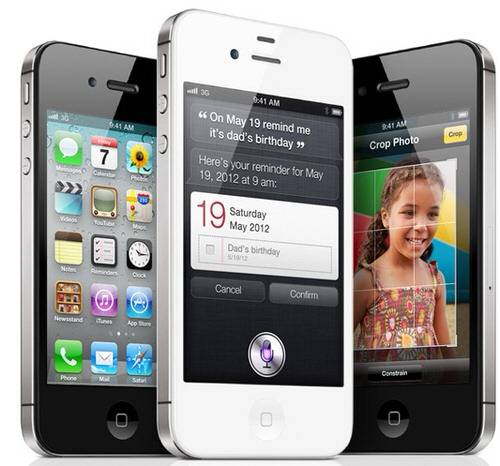

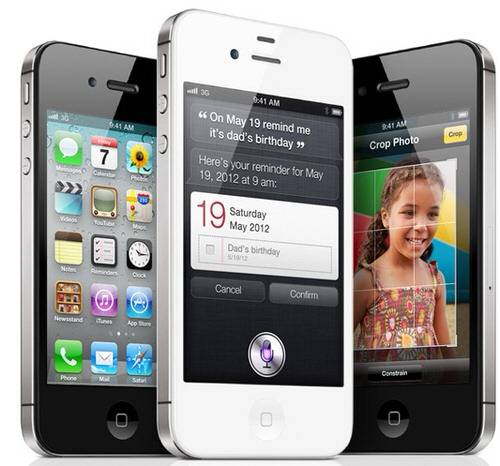

In recent days, the character of our era of consumerism has been put in question. We want what is new, shiny, fashionable. We want it now. With this desire we turn our heads from the consequences it takes to produce our toys, our symbols of status. When The New York Times reports that our gadgets are made in Chinese factories where working conditions can be horrendous, we express outrage and tweet the article from our iPads. The culture we have created comes with the cost of doing business.

The Conditions at Foxconn

The conditions at Chinese factories that make our gadgets can be deplorable. Workers often live in crowded dorms, work more than 60 hours a week, are punished with physical labor and withholding of wages, according to The New York Times report on conditions at Foxconn, which makes Apple’s iPhones, iPad and iPods. In a response to the article, Apple CEO Tim Cook sent an email to Apple employees and the company released a “Supplier Responsibility Report.” This is not a discussion solely about Apple though. Apple is the most valuable company in the world, so it naturally faces the most scrutiny. Other device makers, such as Dell, Nokia, Motorola and Hewlett-Packard, are clients of Foxconn as well.

Apple and Foxconn are just two examples in a larger system. Companies have to weigh the cost and benefits of the manufacturing process. This is not a new dilemma but is a matter of fact within the economy created by the Industrial Revolution. Nor is this quandary solely a matter of high tech devices. Companies like Nike have been cited in the past for the conditions at their manufacturing plants in Asia. How much do you really want to know about the synthetic polymer that is the backbone of much of the world’s textile industry? What about the bread you eat, the TV you watch, the socks you wear?

Framing the Utilitarian vs. Deontological Conversation

“The mere knowledge of a fact is pale; but when you come to realize your fact, it takes on color. It is all the difference between hearing of a man being stabbed in the heart, and seeing it done.” – Mark Twain

Image: Samsung Galaxy Tab

The dilemma created by the source of our products can be explained in a utilitarian framework. Utilitarianism, “is generally held to be the view that the morally right action is the action that produces the most good.” Another word for this is consequentialism. In philosophy, consequentialism is the determination of the moral good of an act based on its consequences.

A utilitarian worldview can be beneficial. The most good for the most people is the highest degree of morality that can be strived for, many believe. The detriments to a utilitarian view are that it does not factor in the needs of the individual. “One must die so a thousand can live.” Is it fair to that one person that must be sacrificed to the greater good?

On the other side of utilitarianism is the concept of deontologicalism. It is the opposite of consequentialism: “no matter how morally good their consequences, some choices are morally forbidden.” Deontological ethics suppose that humans have a duty (the Greek word deon) to support the moral rights of the individual. The boundaries are thus drawn between the concepts of utility and duty.

How do we then rationalize these concepts into our modern era of consumerism? When we hear that four people died and 77 were injured at explosion and subsequent fire at Foxconn, where do we place our own morality on the spectrum between utility and duty? While many of these types of accidents are avoidable on a case-by-case basis, the nature of industrial manufacturing has always lead itself to these types of catastrophes. In a perfect world, everybody would be happy and well fed and the conditions at such factories would never cause harm to those employed. It is something to strive for but a reality that is not easily attained. We have to reconcile our idealism where all parties’ interests are satisfied against the reality of the systems we have created.

This is not a perfect world; we create systems that are fundamentally unfair. The more money is spent and made, the harder it is to change these systems. The two largest device makers in the world, Apple and Samsung, announced this week a sum total of nearly a hundred billion dollars in revenue ($46 billion for Apple, $42 billion for Samsung) in their most recent quarters. The two companies make devices that make people’s lives easier and happier and enable them to perform acts that are a benefit to the greater good. There is little question about the utility that is being produced from an individual perspective and in the dynamics of a worldwide information system. It can also be argued that the existence of companies like Apple and Samsung make the lives of the people that work in their factories better.

There is no doubt that the companies that are customers of factories like Foxconn (and Foxconn itself) can do a better job in maintaining safe, happy, healthy work environments. Yet, implementing changes that are beneficial to those workers may also lead to an imbalance in the system. Can the diverse nature of technological consumerism be monetarily supported if the efficiency that is demanded by companies like Apple and Samsung from factories like Foxconn is diluted?

For The Good Of Whom?

When we speak of the most good for the greatest number of people in this scenario, who are we talking about? The good of the consumer, the good of Apple’s shareholders, the good of the plant owners or the good of the workers? The different stakeholders will give you an array of answers.

Consumers want high tech devices can make their lives simpler, more efficient and arm them to do their jobs and make the world a better place. Shareholders want profits. Similarly, there is profit motivation for those who own the factories. The good of the plant owners theoretically could mean the good of the factory workers as the factory owners can open more factories, employ more people and create a higher standard of living for their employees.

The good of the factory worker… well, that is what is missing from the conversation. From a utilitarian perspective, what is morally right for the factory worker may not be of the greatest good to the other parties. From a deontological perspective, the other parties have a moral duty to uphold the rights of the factory worker. This is the dilemma that must be reconciled.

We are stuck at a crossroads. How to balance the utilitarian systems that provide the world with the devices that make peoples’ lives better versus the deontological morality of those systems. This is not a new dilemma but a scenario that has been played out thousands of times throughout the course of humanity, from the feudal systems of agrarian Europe to the factory towns of New England in the 19th century to the manufacturing plants in Chengdu that make our computers today.

While we all hope that humanity can rise to create a more perfect world where the balance of human moral values is no longer a question, it is not the world in which we live.

That is the cost of business.