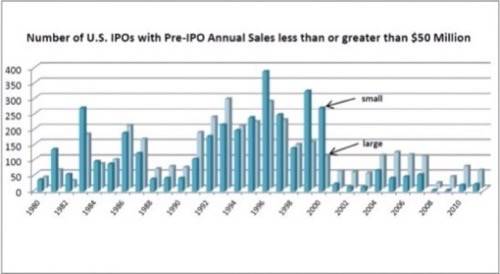

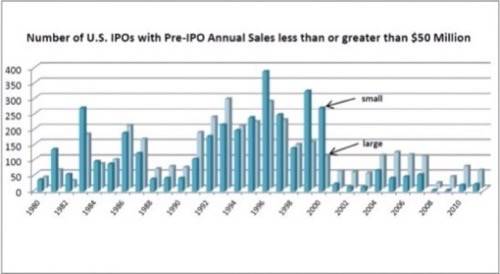

Number of U.S. IPOs by year, 1980-2011, with pre-IPO last 12-month sales less than (small firms) or greater than (large firms) $50 million (2009 purchasing power). [Credit: Prof. Jay Ritter, for testimony before the Senate Banking Committee]

The fact that a great deal of the content produced by tech news sites concerns startup companies might make an observer from another planet think America is a veritable nursery for brilliant business ideas. The real truth is, since the “Internet bubble” burst in 2001, initial public offerings have not resumed the vitality levels of the late 1980s, let alone the boom years of the ’90s.

This week, President Obama is scheduled to sign into law a bill that eases the Sarbanes-Oxley (SOX) auditing and reporting requirements on new companies looking to go public, as well as effectively legalizing the principle of crowdfunding – pooling the resources of micro-investors to make small batches of seed capital available to early-stage startups. It’s a move that’s not without controversy, and not even the people who are happy with it are completely happy with it. But it could affect one thing right away: the level of buzz and information surrounding young IPOs, which no longer have to keep mum.

Make Way for the On-Ramp

The most important belt that the Jumpstart Our Business Startups Act loosens concerns the amount of capital a new company may raise through the sale of securities in a 12-month period. Previously $5 million, the securities sales cap will be raised to $50 million. That cap will now specifically apply to a broader group of small companies: those with annual gross revenues of $1 billion or less (adjusted for inflation), within a five-year interval from the sale of its first security.

We’d better get used to the new phrase, emerging growth companies (EGCs). It’s the term proposed by the National Venture Capital Association (NVCA) in a proposal last October (PDF available here), and this week it will be codified into law. It refers to this specific, new group of young, low-revenue companies for whom some of the SOX reporting regulations will no longer apply.

The NVCA recommended the five-year period as part of what it called the “IPO on-ramp.” As the proposal read, “We recommend that companies with total annual gross revenue of less than $1 billion at IPO registration and that are not recognized by the SEC as ‘well-known seasoned issuers’ be given up to five years from the date of their IPOs to scale up to compliance. Doing so would reduce costs for companies while still adhering to the first principle of investor protection.”

In testimony before the Senate Banking Committee last December, Kate Mitchell, former head of the NVCA and currently Managing Director at Scale Venture Partners, stated that EGCs were overdue for relief. Her case was that the reporting requirements applicable to public companies like Exxon and Apple were strangling small companies, making them less attractive to investors.

“As someone who has spent the last 15 years seeking out, evaluating, investing in, and helping to build promising young companies, I cannot overemphasize the value of a robust and accessible IPO market,” stated Mitchell. “In our survey of emerging growth company CEOs, 86% of respondents listed accounting and compliance costs as a major concern of going public… Over 85% of CEOs said that going public was not as attractive of an option as it was in 1995. Given these concerns, for CEOs of successful companies deciding between pursuing an IPO or positioning themselves for an acquisition, the scaled disclosure and cost flexibility provided by the bill could help make an IPO the more attractive option.”

Because EGCs were under the same burdens to remain quiet as the larger, established ones, Mitchell and NVCA argued, they couldn’t generate enough buzz. You read that right: Not a lot of people are that interested in startups.

This argument raised objections from Prof. Jay Ritter of the University of Florida’s prestigious Warrington College of Business Administration. In testimony before the same Banking Committee last month (PDF available here), Prof. Ritter alluded to what appeared, at least to him, to be a plethora of news sources emerging in just the past few years devoted in large part to emerging tech startups – perhaps you’ve read a few yourself.

Citing data from a study he conducted in conjunction with two Hong Kong universities last month entitled “Where Have All the IPOs Gone?”, Ritter acknowledged that the reporting requirements were a burden for EGCs, but argued it wasn’t enough of a burden to keep the tech bubble of the ’90s deflated throughout the 21st century.

“I agree with the conventional wisdom that these factors have discouraged small companies from going public, but I believe that only a small part of the drop in small company IPO volume can be explained by these factors,” stated Prof. Ritter. “Instead, I think that the more fundamental problem is the declining profitability of small firms. In many industries, over time it has become more important for a firm to be big if it is to be profitable. Emerging growth companies are responding to this change in the merits of being a small, stand-alone firm by merging in order to grow big fast, rather than remaining as an independent firm and depending on organic (internal) growth.”

The hole in the NVCA’s data, the professor alleges, comes from a factor that perhaps would be obvious if anyone bothered to read those non-existent venture sites: mergers and acquisitions. In short, small companies aren’t entering the IPO state because they had no desire to be independent in the first place. The earnings, the UF team believe their data indicates, come from being part of someone else’s desire to scale up.

States the Florida/Hong Kong study, “Our explanation is that earnings are higher as part of a larger organization that can realize economies of scope and economies of scale, and this regularity is the main reason why many small firms are choosing not to remain independent, but instead merging as a way of getting big fast. If our explanation is correct, regulatory reforms aimed at restoring the IPO ecosystem will have only a modest ability to affect IPO volume.”

Two’s Company, 2,000’s a Crowd

The crowdfunding business is already well under way, as evidenced by the existence of online marketplaces such as Appbackr.com. The business itself was technically illegal, although its practitioners were never prosecuted. Once the JOBS Act is signed, new statutes will effectively legalize the practice, while limiting the sale of all crowdfunding transactions with a particular business to $1 million per year.

While The Economist hailed the passage of the bill as a whole, it cast a skeptical eye on simply enabling crowdfunding sources to exist without firmer regulations. “Crowdfunding is an efficient way for entrepreneurs to raise seed capital,” the editors wrote. “But it is also a good way for hucksters to fleece suckers.”

The magazine’s comments play into the now-legendary testimony last November of Columbia Law School Professor John Coffee, who dubbed the crowdfunding bill that was later incorporated into the JOBS Act “The Boiler Room Legalization Act of 2011.” Coffee took issue with an aspect of that bill – which will indeed be signed into law – that increases the minimum shareholder number threshold for SOX reporting restrictions from 500 to 2,000. “There is no need for such an open-ended exemption, largely benefitting larger firms,” he told Congress, “or for such a dramatic retreat from the principle of transparency that has long governed our securities markets in order to spur job creation at smaller firms.”

But in her arguments for the JOBS Act, the NVCA’s Mitchell stated that rolling back these requirements could save EGCs as much as $2 million each per year, suggesting that startup firms may have owed more in reporting costs than it was ever possible for them to raise through crowdfunding alone.

Stock image by Shutterstock.