One fine day, we might all ditch our smartphones in favor of smartwatches or other wrist-worn devices that do everything that a smartphone can do, but better. That day is not coming any time soon.

The ideal smartwatch would be able to stand by itself without requiring help from a smartphone to perform its mojo. It would not need to be tethered to a smartphone, so companies like Apple, Google, Samsung and Microsoft would not be able to tie you into a closed-looped ecosystem where to use their smartwatch, you would have to own their smartphones too.

Unfortunately, there are practical limitations to building this ideal smartwatch. It all comes down to components – the hardware inside the watch – and an industry playing “wait and see” to learn if this next fad in wearable computing will be a consumer hit.

(See also: The Smartwatch Arm Race: Don’t Lock Us Into A Closed Loop.)

Battery Life, Heat & Efficiency

The problem is that the components to create the ideal smartwatch – device-independent but small enough to be practical – do not really exist yet. The biggest technical challenges to creating such a smartwatch are related to power consumption. Surprisingly, that does not necessarily have much to do with the battery inside.

Power usage in mobile devices is more about the operating system the device runs (iOS, Android, BlackBerry etc.), how the device’s processor (CPU) manages energy efficiency and the size and capability of the cellular modem. Loading and running a smartphone-style operating system on a watch-sized device would require significant processing and modem power.

Robert Thompson, the director of smart devices, consumer segment, at component maker Freescale, laid out three distinct challenges to creating a cellular modem for the ideal smartwatch:

- Size of the die for the modem chip.

- Power consumption.

- Cost: the amount of research, development and change to manufacturing processes needed to achieve the required size and power-consumption.

“Even if Qualcomm today could reduce the die size or the size of their cellular modem that might fit into a smartphwatch… and therefore reduce the power consumption and the heat dissipation to a level that would allow it to be used as a wearable device, there is no silver bullet on the power management [integrated circuit] front,” Thompson warned.

The modem makers would need to see significant consumer interest in wearable devices to feel safe making the investment needed to create components that could fit in smartwatches, Thompson said. He adds that companies like Apple, Google or Samsung could foot the bill for such improvements, but that is not likely to happen in time for the first wave of smartwatches.

“That cost structure, for obvious reasons would make the margins extremely high and make it almost impossible for any of the major players apart from maybe an Apple, Google or Samsung, that have the purchasing power in the millions of units, to have any cost structure that would make this smartwatch appealing to the majority of people,” Thompson predicted.

For now, Thompson said, none of the major potential smartwatch makers are really considering the use case for the “ideal” smartwatch. Most are still trying to figure out how to make the device as low-power as possible while tethering the device to a smartphone.

The Art Of The Possible

Consumers have a kind of blind faith that tech manufacturers will, eventually, be able to create the technology of their dreams. They may have a general notion of Moore’s Law (where the capability of chips “doubles” every two years) and a rudimentary knowledge of what the hardware specifications in their smartphones actually mean.

Turning that faith into reality doesn’t get any easier as expectations continue to ratchet up.

Technological innovation does not happen overnight. More than a decade of research, development and evolution of manufacturing processes was required to create workable smartphones. Gadget makers live in a world constrained by the art of the possible – and they constantly strive to expand those constraints.

Based on the current component state-of-the-art, Thompson said he sees two ways that gadgets like smartwatches can evolve: as “hub” devices for other wearable computers and as data-collection devices that can connect to your home network.

“I think the next evolution that smart watches can take is that they don’t have to talk just to your smartphone or tablet, but can also talk to your home gateway,” Thompson said. “I think that in the home network that we are going to have Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) added to the many protocols a home gateway will connect to. So your smart watch doesn’t just have to be a companion device to your smartphone, it can pass data directly to the gateway and then to the cloud where it can be analyzed and then pushed down back to your hub device.”

As hub devices, smartwatches would manage power by only on turning its power-consuming features (CPU, sensors, modem, Bluetooth) when needed. For instance, if a smartwatch wearer was exercising or checking messages, the device would turn on, collect the data needed, allow the user to perform the desired action then go back to sleep. It would turn on to connect to a network (through a smartphone or Wi-Fi network) to send that data to the cloud and back.

Thompson expected that type of functionality to dominate smartwatches in the short term.

“From a technological perspective, all the components are there, from a cost perspective you could argue that it is achievable today because a multi-combo chip of Wi-Fi, GPS and Bluetooth Low Energy can be used and then incorporated into a smart watch today,” Thompson said.

That’s great, and many people will be thrilled to get a smartwatch tethered to their smartphone. But the ideal, independent smartwatch will have to wait for a new generation of hardware components.

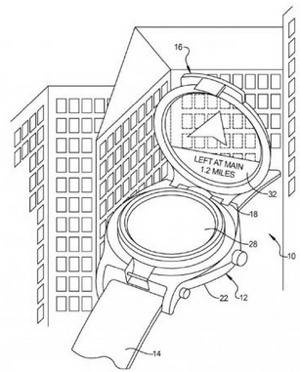

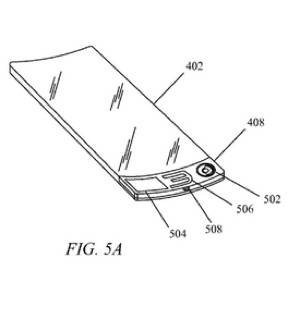

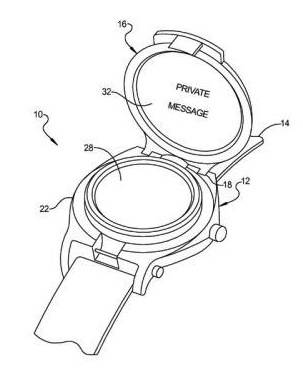

Lead image by Aaron Muszalski. Black-and-white images from Google’s smartwatch patent filing.