It’s been said that the French never throw away bread and books, and a week in Paris confirms just that. But while Parisians love books and hold onto them, share them and resell them in the hundreds of used books stores in the city, they seem to have little use for the tablets and e-readers most hardcore American readers have embraced, albeit some more begrudgingly than others.

France is by no means a technological slouch. During a recent trip overseas, our credit and debit cards didn’t always work because they didn’t have the fraud-protection microchips that are now standard in cards issued by European Union banks. Most advertisements we saw on the Metro had QR codes, and we were able to check Facebook thanks to free Wi-Fi at Versailles and other heavily touristed areas.

But the French are able to eat carbs and obscenely rich foods by not overindulging like their American counterparts, and the same levels of moderation seem to hold true when it comes to technology. Cafes are still arranged with small tables and side-by-side chairs that foster conversation and discourage work. We didn’t see people walking around in the pose familiar on so many American sidewalks, neck slouched to stare intently at one’s hands. Starbucks and a few other coffee stores offer free Wi-Fi, but it seems to be used about as much as the to-go cups that would actually require someone to walk, commute or drive while taking their morning coffee.

A Different Take on Mobile

By the end of our first full day, my girlfriend noted “We’re definitely seeing more people holding cigarettes than smartphones,” and that trend remained true for our entire time there.

When we did see people using smartphones, it was often to huddle over a photo, a video or a text message with a friend. They were retrieved from briefcases and purses, not kept on a table or breast pocket. We also saw several cracked screens on older Blackberries and iPhones: Most of the people we know back home in the States would use such a calamity to upgrade to a newer model. But the French, by and large, seem content to make due with a scuffed-up but still perfectly usable model.

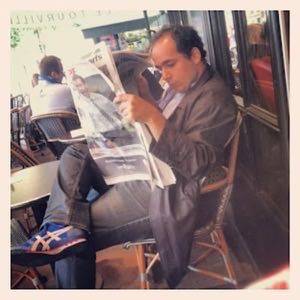

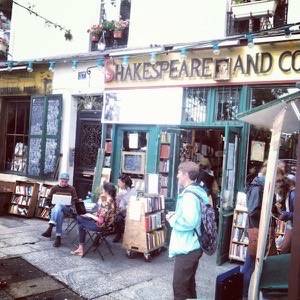

Still, none of that would explain why the French have been reluctant to embrace e-readers. The French are well-read: Newspapers still fly off newsstands, and we saw people reading magazines everywhere we went. Used book dealers lined the kiosks along the Seine, and newer titles are readily available in any one of France’s 2,500 bookstores. But the only Kindles we saw were clutched in the hands of American travelers on our flight back home; the only iPads we saw (other than our own) were being used as cameras.

Blame Slow e-Book Sales on the Government

Some French are reading e-books: They accounted for 1.8% of all general consumer book sales last year in France, but that’s not anywhere near the number of the American readers who have embraced e-books, where they accounted for 6.4% of all general consumer book sales last year and are increasingly accounting for bigger chunks of the magazine and newspaper sales markets, as well.

That is also evidenced in the brick-and-mortar retail market, where French-language bookstores have continued to thrive, grow and open while English-language bookstores have struggled. (Overall, book sales in France increased an average of 6.4% annually between 2003 and 2011.)

But, as reported by The New York Times, the biggest boost for publishers and retailers has been the French government’s willingness to build protections for traditional publishing into law. Last year, while French publishers watched in horror as e-books ate away at the printed book market in the United States, they successfully lobbied the government to fix prices for e-books too. Now publishers themselves decide the price of e-books; any other discounting is forbidden.

There are also government-financed institutions that offer grants and interest-free loans to would-be bookstore owners.

Still No Reason to Invest in Paper and Ink

The takeaway is that, despite a global economy, the strategies for both new tech and mobile products usually have to be custom-fit for different markets, and that cultural norms can vary as companies move across borders.

But even the French know that traditions bow to change. Some bakeries now reheat frozen baguettes instead of baking them twice-daily on premises, and even the most diehard French bibliophiles know the printed book’s future is best measured in years and decades, not centuries. Earlier this month, French publishers reached an agreement that will allow Google to sell digital versions of their books.

“We are in a time of exploration, trial and error, experimentation,” Bruno Racine, president of the French national library, wrote in his 2011 book, Google and the New World. “Many scenarios are envisioned. The least probable is certainly that of a victorious resistance of the paper book.”

Photos by Dave Copeland.