Apps are reaching an inflection point. Now that zillions of apps are available to serve every imaginable purpose, there are two ways for them to keep us interested. They can either melt into the background and do their jobs with minimum fuss, or they can force us to pay attention to them. Which option sounds better in the long run?

This is a story of two apps. One has evolved from an inconvenience to a convenience, the other has done the opposite.

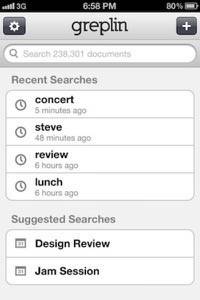

Greplin: The Business of Friction

I loved Greplin. It provided a critical service better than any other app: It searched across everything. You logged into your various cloud things, your Gmail, your Evernote, your Dropbox, your Google Docs and Calendars, your Facebook and Twitter feeds, and it gave you a search box that helped you find anything in any of those places. It indexed over a million of my documents, messages, reminders and notifications, no matter how small. It was one of the handiest apps on my phone.

I didn’t need Greplin often. But when I did, I really needed it. I would be in a meeting and need to recall the contents of a document that could have been in a number of places. By far the quickest way to find it would have been to pull out my phone and search Greplin. But I launched the app only once every couple of weeks.

You could pay Greplin to unlock the ability to connect to some services, but you could also do it by inviting friends to Greplin. I found it easy to get all the services I needed for free, and I bet I use a lot more apps than the average person.

Now, a free app has to get you to launch it all the time if the publisher has any hope of turning it into a business; frequent use brings the opportunity to display lots and lots of ads. Greplin didn’t inspire its users to launch it that often. So Greplin “pivoted,” relaunching as Cue. While it still has a search button way down in the corner, Cue is designed for an altogether different use.

Taking advantage of Greplin’s connection to calendars and email and all that, Cue sends push notifications that remind you of every event in your entire life. That, of course, prompts you to open the app. Often. Like, many, many times a day. That may be better for business, but it’s a raw deal for users. Notifying users of upcoming appointments is not a new service. All phones can already do that. Search across the cloud was profoundly useful, but now it’s a minor feature of an app that has become annoying and redundant.

Paying for Convenience

Contrast Greplin’s trajectory with that of Square. Square’s first product was a mobile app for accepting payments by credit card using a plastic dongle. It allowed regular people to pay each other with plastic, a new convenience, but it required that they keep track of this tiny gizmo if they wanted to be on the receiving end.

To drive more usage, Square did the opposite of Cue. It iterated itself out of the picture. The Pay With Square app stores customers’ credit card info, and merchant users keep a “tab” for each customer under his or her name. A user just has to open the tab in the app when getting ready to buy something, and the seller just matches the face and the name and processes the payment.

The new app even allows geofencing, so it can open your tab automatically whenever you come near a store, food cart or whatever it is. Your phone doesn’t even have to come out of your pocket to handle the transaction.

The Long Run

Which of these experiences sounds like the future?

Cue’s business is mired in an old model devised for the desktop Web. It demands eyeballs, reminding its user to fiddle with a computer as often as possible.

Square is an example of the new promise of mobile. When we carry computers around with us, packed with sensors and storing our account info, the right kind of software can help us get around in the world while operating undercover.

But this is all bound up in how an app does business. If Greplin isn’t willing to charge its users for the convenience, it has to show ads, so it has to be annoying. Square is in the payments business, so it can take its cut as money changes hands, but it has the same hurdles as Greplin: It has to get people to use the app often, even in a sea of alternatives.

With iTunes and the App Store, Apple proved that people will pay – even just a little bit – for digital convenience. The alternative for free apps is to gamble on this question: How much annoyance will users tolerate to get something for nothing?