If you’ve driven through San Francisco’s Misson neighborhood on a Saturday afternoon seeking a place to park for a brunch you’ll spend an hour waiting in line for, you know how difficult it is to find a spot for your vehicle.

When Apps And Real Life Collide

To one team of entrepreneurs, the parking problem here isn’t a problem at all. Instead, it’s an opportunity to build a business by giving those who are willing to pay a little extra a hassle-free parking spot.

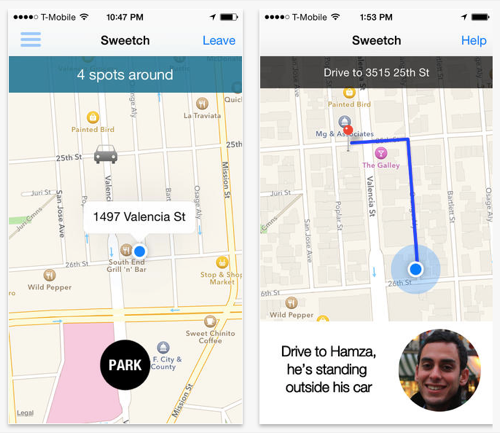

Their app, called Sweetch, a moniker that combines “switching” places and making parking “sweeter,” lets users pay $5 to get a parking spot from someone who is leaving. Drivers, in turn, receive $4 when they list their own spot and someone claims it.

According to cofounder Hamza Ouazzani Chahdi, it’s designed to reduce traffic congestion by limiting the time people spend circling for a space.

“As the inventory of parking spots on-street will not increase, the best way to improve the situation is to provide information to people about parking spot locations and availabilities,” Chahdi said in interview.

He said that while the Sweetch team isn’t originally from San Francisco, they’ve spent the last six months observing the parking situation and talking to people in the Mission to help find an appropriate solution.

Mission residents are not impressed.

“Sweetch is not making parking problems better overall; it’s making it so a person with money is more likely to get a spot,” software developer and Mission resident William Pietri told me. “It makes the problem worse in that it encourages people to wait for a parking space for people to come along and pay for it.”

To critics like Pietri, Sweetch is just a company trying to make a buck from public goods. And its product is seen as the latest in a slew of apps that widen the gap between people who can pay extra and those who can’t.

Such frustrations are nothing new in the Mission, a historically Hispanic neighborhood already dealing with an influx of tech workers and a resultant spike in rents—to say nothing of the giant corporate buses that shuttle them to their jobs in Silicon Valley.

While walking down a neighborhood street one day, Pietri saw Sweetch employees advertising their app.

“I told them it was an abomination,” he said.

He then saw a Sweetch pitch on the community-based social network Nextdoor. Pietri was not alone in his distaste for the app—his neighbors weren’t happy. There were 65 replies, the majority of which condemned the service and the people building it.

Pietri equates Sweetch to a high-tech equivalent of panhandlers who jump in an open parking space, wave a driver in, and ask for cash—not the environmentally- and community-friendly startup the founders claim to be.

Chahdi says these fears of people squatting in spaces are unfounded, because the dollar amount is relatively low, and they are not trying to build an app for people to make money. The fee, he argues, is meant to create an incentive to let others know when you’re leaving a parking spot.

However, if you list your parking spot and no one claims it, you don’t get any money. So Sweetch is arguably motivating parked drivers to wait a few extra minutes to get their $4.

Parking frustration, of course, is widespread across major U.S. metropolitan areas. And Sweetch isn’t the first app to try and solve that problem—it’s not even the only app that facilitates payments between drivers. Startup MonkeyParking turns parking spaces into auction items, and gives the spaces to the highest bidder.

Among other things, it’s not even clear whether parking apps like Sweetch are legal. At some level they amount to trading in a commodity that neither party can own. If anything, street parking spaces are held in public trust by the city government.

A representative from the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency told me, “We recently became aware of these applications and are currently working with other agencies to determine their legality and how they impact efforts to effectively manage parking in San Francisco.”

A City Disrupting Itself

The City of San Francisco is actively working on improving parking issues. In 2010, the city rolled out SFpark, a pilot project that aims to improve the availability of parking by boosting meter fees in a few heavily trafficked neighborhoods during periods of peak demand. The idea is to discourage squatting at low rates.

The program uses meter sensors to detect open spaces, and it offered an app that could direct drivers to available parking in spaces and garages. But unlike Sweetch, the only thing the city charges is the meter fee.

In fact, SFpark has open-sourced its parking data and encourages developers to use the public API to create new apps that benefit the community.

There’s hope that SFpark will expand to cover more areas, bringing the same time-saving efficiencies these pay-to-park apps promise, but keep the parking-related revenues for the city, which uses them to maintain infrastructure, for instance, roads we drive on in the first place. First, though, it has to pay for its own operation: The pilot program is currently under evaluation and the sensor batteries have run down, so the app isn’t currently reporting real-time information on empty spaces.

Local governments are notoriously slow when it comes to implementing change—unlike startups, local officials are burdened with paperwork and procedures. They have to answer to all their constituents, not a small set of customers. So it’s natural for entrepreneurs to look at a problem stuck in a logjam of legalities and envision a quick, technocratic solution in the form of an app. Sweetch is arguably providing a look at available parking spaces that the city has promised but isn’t currently offering.

Is Sharing Really A Business Model?

When I asked Chahdi about the legalities of selling parking spaces, he said, “No one is selling a spot because it is a public asset and does not belong to anyone. The members of our community are sharing private information about the location of their car.”

That argument seems tendentious, since you’re paying $5 for a patch of asphalt, not a piece of data. Since 2003, it’s been illegal to ask people for money in parking lots or when they’re exiting cars in San Francisco. It’s not clear why putting an app on top of the experience changes things.

Pietri, a startup mentor and entrepreneur himself, said that Sweetch is emblematic of the industry’s flaws—a solution to a problem that makes sense to the wealthy, but that locals hate.

“I came from a position of wanting to like these guys,” he said. “But they don’t quite get that the purpose [of a startup] is not to make money, but it’s to create value for other people and make money along the way.”

Entrepreneurs won’t stop trying to simplify everyday activities with mobile technologies. The real test for this growing group of apps and services will be to see how many, and which types of people the value is being created for, while balancing the desire for simplicity with the wants and needs of the local community.

In the meantime, some drivers will have no choice but to circle an extra 20 minutes waiting for a parking spot to open up. Those who can wil pay extra for the privilege of parking quickly. Next up: Paying someone to stand in line for them at brunch.

Lead image courtesy of Pelle Sten on Flickr