The other evening, I got into a conversation with an older gentleman whose name I have since forgotten. His main complaint is that writing today feels more like “blurbs” formatted for word-skimming Internet users – more like chunks or nuggets and less like hearty, homemade meals. He told me to check out the writer Don DeLillo. I didn’t have time to whip out my iPhone and make a note, so I just catalogued it in my mental Instapaper-like memory, marking it “read later.” Who knows when “later” will ever come. For now, at least I’ve made it to Don DeLillo’s Wikipedia page, which I have just Instapapered for later.

So what does this have to do with writing for the Internet, story virility and Digg? A new study out of Cornell University by Tad Hogg and Kristina Lerman called the Social Dynamics of Digg looks at ways to predict a story’s popularity on Digg, which many believe is over. Before we even look into the study, a caveat and something to ponder: As Internet users, are we becoming even more formulaic in our ways of thinking and clicking? Or is this simplification of story headlines actually driving us to dig deeper into the “how’s” and “why’s” of stories? Perhaps the “Predicting a story’s popularity on Digg” will provide some answers.

Tech bloggers declared Digg dead nearly one year ago today. Regardless of if it really is over, however, there’s still data to be had. And the Internet, like a scavenger bird searching for last remains, will continue to pick at Digg.

So about Digg: If you didn’t already know, it supposedly relies on crowd-sourcing and social “follow” links to discover stories. The researchers looked at stories that were primarily of interest to a users’ friends versus those that were of interest to the entire user community. Using this model, they predict a story’s popularity from early users’ reacts to the reliability of such predictions. Indeed, Digg is a treasure trove of data, as I discovered in my horses on the Internet story.

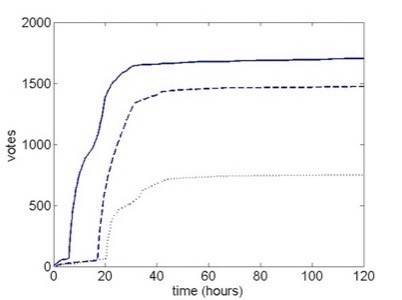

This first figure looks at the popularity of three stories over time, as measured by Diggs. It consistently shows that new stories tend to plateau somewhere between 20 hours and 40 hours post-submission to the site. In these instances, the spike corresponds to front page promotion.

Digg is less like a thriller-type rollercoaster and more like a slow rise to a rollercoaster meant for adults. It takes a bit of time to get to the top, but then once you arrive there is a nice, easy plateau. No crazy drops and dips like a rollercoaster meant for an adrenaline-filled adolescent, you see.

Of course, not every rollercoaster (in this case, story submitted to Digg) is going to be very popular. Some are just duds, costing the amusement park time and money – and eventually shutting down. The researchers aim to understand why some stories were more popular than others, how popularity grows and why it saturates, the role social networks play in this popularity contest evolution and if this behavior can actually be predicted.

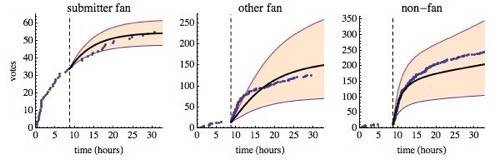

Digging depends on interest and popularity. It relies on the idea that the most interesting stories will be the most popular, and the most popular stories are in fact the most interesting. If the stories are interesting but not popular, users will have a harder time finding them. The researchers call this the “visibility” factor. The more a user submits stories, the weaker the visibility of their current story is. Visibility grows as soon as a story hits the front page, and then decreases as more stories get promoted. Every story that’s submitted is also visible to the Digg user’s fans.

Therefore, popularity is closely correlated with interestingness, which is determined by number of Diggs the story receives. The researchers did separate interestingness from visibility in order to determine more than just how much a story was Dugg – in other words, a measure beyond just number of diggs.

The researchers also note that many top users submitted a large number of the Front Page stories, which it notes is “of some controversy on Digg.” It also discovered that stories receiving Diggs from a submitter’s actual fans were less likely to blow up than stories that spread amongst non-fans. So if you a story to be popular on Digg, your friends don’t really matter.

Of course, take all of this with a grain of salt. Says the commenter hydroplane: “The original Digg may have been crowdsourced but the stories on this version are clearly cherry picked by propaganda ministers.” Says lucas123: “Who knows what makes for a popular story these days? It seems to be all over the place, and it seems to have little to do with story quality.” How often do you see an ad-sponsored post sitting on the front page “for days, weeks at a time,” he asks. “This site is such a far cry from what it once was.”

In the meantime, the Digg Social Reader continues to collect data from Facebook users. There’s still time to dream…of horses, anyway.