Two reasons many security engineers have proclaimed “endpoint security” dead have to do with the inversion of forces in the network. First, conventional endpoints like the PC are no longer the targets of malicious actors, they’re the agents. And second – a fact which is no longer in dispute – the “endpoint” has moved to the smartphone and the tablet.

It’s a fact made all the more clear by the results of a Harris Interactive poll taken in conjunction with… well, endpoint security tools company ESET. It has been adapting its delivery model for antivirus in light of the fact that the old endpoints aren’t at the end any more. So it probably swallowed just as hard as anyone else when it admitted the following poll numbers: While some 24% of employed adults now store some elements of their companies’ private data on their smartphones, and 10% on their tablets, only 25% of those adults have auto-lock enabled on their smartphones, and 33% have it enabled on their tablets.

An ESET spokesperson told ReadWriteWeb this afternoon that the survey, conducted for ESET by Harris Interactive, sampled responses from 1,320 employed U.S. adults aged 18 and over.

Assuming that new endpoint device gets stolen, the numbers don’t look promising for the corporate data on that device. Only about one-third of BYOD devices, including smartphones, tablets, and laptop PCs, utilize any type of encryption policy for corporate data. The Web is nearly three decades old, and encryption of sensitive data does not yet happen on half of devices.

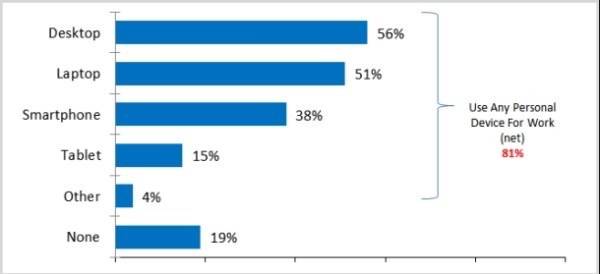

Percentages of users in the Harris Interactive/ESET survey who used any personal device for work purposes. [Chart credit: ESET North America]

In a recent blog post, ESET security researcher Cameron Camp asked readers to imagine themselves in an airplane watching the passengers wile away the time with their latest personal devices, but to imagine them with the perspective that a corporate security policy manager should take.

“I’m sure you’ve seen this scenario: Halfway through the flight a user switches from super-critical pieces of corporate work to checking out the app they downloaded while waiting in the airport terminal. Obviously that’s a potential problem: bored users looking for cool things to install on their hip new piece of hardware. Maybe there’s a compelling reason to get that app, but is there a security context in place whereby this activity is vetted, especially when they are connecting that device to the company network? Beyond that, are basic measures in place to protect the data on the device if it falls into the wrong hands?”

We spoke about the “bring-your-own-device” phenomenon (BYOD), and the measurements of its impact on business, with Eric Chiu, president of virtualization security provider HyTrust. As Chiu puts it, “When you think about it, you’ve got your private cloud – your own data center in this virtualized world – and you also have SaaS applications like Salesforce, then you’ve got rented infrastructure as a service, and then you’ve got people bringing in their own laptops and mobile devices – all these different dynamics going on in the enterprise where you’re hosting data internally and externally. You’re giving people any means of access that they want. How do you secure that?

“Our view is that IT eventually transforms from being an operational functional – racking and stacking and managing those resources,” Chiu continues, “to a control and governance function.” He tells us about a real-world hypothesis that HyTrust tested on its own employees: Chiu offered his employees their choice of a BlackBerry or an iPhone, and then for each employee, provisioned the phone of her choice. But that was as plain as Chiu made the choice – iPhone or BlackBerry, take your pick. Many complained that they weren’t being given a modern choice.

So Chiu changed HyTrust’s policy for BYOD. Now, it’s up to his IT team to administer access to the applications which employees access on their devices. Which means if someone’s fired, that access must be deactivated. The move was made from provisioning and control, to access and governance. “Companies have to be able to do that, for all of these new ways that people are accessing and hosting data… I see Dropbox as a huge security hole! I don’t know how many big companies that have shared confidential information with me via their personal Dropbox account. And code, too! People are uploading code snippets because it doesn’t get through their e-mail system, and there’s no easy FTP. They’re putting all this confidential information in this personal Dropbox account.”

Chiu points out that there’s just one synchronization cycle for Dropbox. So if an employee is terminated, there’s a very good chance the confidential data in his personal Dropbox account will get synchronized with his phone even if it were to be deleted from there.

You might have pictured a low-level employee getting away with a juicy nugget of confidential data. ESET’s Cameron Camp is thinking a little higher. He writes: “Slick new mobile devices are often used by more senior staff, so you’d hope they would act more securely by default, but do they really?”

It’s worth noting that the 1,320 U.S. adults responding to the Harris survey were those employed, among the 2,211 adults who were contacted.