ReadWriteBody is an ongoing series where ReadWrite covers networked fitness and the quantified self. This week, it is presented by ComforPedic IQ.

I have a new plan for improving my health and fitness: I’m going to sleep on it.

Here’s why I’m thinking about putting in some more pillow time—and the technology I plan to use to make it happen.

Why Sleep Is A Weighty Matter

I got some unwelcome news on the scale recently: I’ve crossed 200 lbs. again, my personal weight Rubicon. After losing 83 lbs. four years ago and maintaining in a healthy range since, I’m determined not to let things slide.

When it comes to my health and fitness, there are a lot of warring voices in my head vying for attention. The delusional gym rat in me wants me to believe that it’s all muscle, the result of a four-month stint working out with the improbably butch-sounding Juggernaut Cowboy Method to improve my bench press. The logical self-quantifier, on the other hand, argues that if I’m gaining weight, something’s out of balance.

For years, I’ve diligently tracked my nutrition and exercise, and there aren’t any easy answers there. By most estimates, I’m eating at or below maintenance level. The latest science tells us that the old “calories in, calories out” approach to weight loss doesn’t match up to reality. Stress, fatigue, and inflammation from various sources play havoc with our hormones and interfere with our bodies’ ability to regulate themselves. Yes, you’ll gain weight if you stuff yourself. But if you’re managing your food intake and getting regular exercise, like I am, it may be time to look elsewhere.

Sleep is a pretty obvious place to explore. Studies have found a link between improved sleep quality and weight loss.

See also: At A Glittering Tech Showcase, Dreams Of A Good Night’s Sleep

I didn’t realize it, but I’d been tracking my sleep for more than a year using iHome Sleep, a free app that came with my iPhone dock/clock-radio. When I started poking around in the app, I discovered it had extensive sleep statistics. The limitation of the app, though, is it only measures the time between swiping to start sleep and swiping to silence the alarm.

Another simple sleep tracker is Path, the much-maligned social app. While Path never gained widespread popularity in the United States, it has some neat features I still don’t see in other apps, including the ability to tell your friends that you’ve gone to sleep and that you’ve woken up. The feature is handy as a subtle do-not-disturb signal, but it doubles as a sleep-tracking tool.

Then there’s the LifeTrak Zone C410 activity tracker, which estimates sleep time based on motion. I’ve found it sometimes overestimates how long I’m actually asleep, versus lying in bed, but it provides a nice visual gauge of my sleep.

Waking Up Without The Blare

My husband hates my alarm, though, and there are studies that suggest an audible alarm may be bad for your health.

I’ve experimented with two ways to wake up noiselessly, both using wearable devices.

With the Pebble smartwatch, which picks up notifications from my iPhone and vibrates with every new alert, I used do-not-disturb settings as a way to hack a context-sensitive alarm. At 5:45 a.m., my do-not-disturb settings turn off, and the notifications start coming in. If it’s a slow news day and my writers on the East Coast are quiet, I don’t get a lot of notifications and I can sleep in a few more minutes. If the notifications start shaking me awake, I know it’s time to hop out of bed.

There’s a sleep-tracking app called Morpheuz for the Pebble, but I found it so frustrating to use that I quickly abandoned it. Pebble has also partnered with wearables maker Misfit on an app that turns the smartwatch into a fitness tracker with plans to include sleep features, but those aren’t available yet. No matter: I already have lots of ways to track my sleep.

I’ve also been trying out the Jawbone Up 24 wristband, which tracks activity and sleep. Like the Pebble, the Up can vibrate to wake you up, and it even has a clever feature to adjust its silent alarm based on when you actually get up. If you start to stir before your scheduled alarm, it will vibrate sooner, eliminating that unproductive, unrestful time when you’re staring at the ceiling waiting for your alarm to go off.

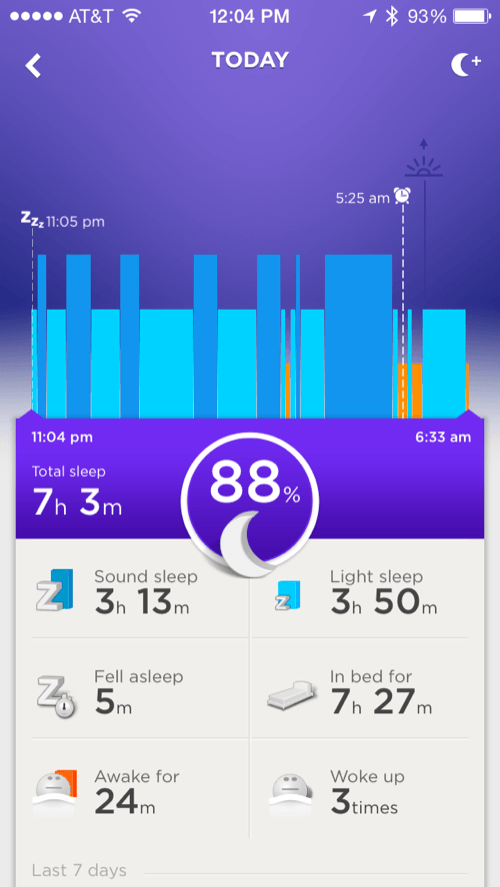

The Up 24 is limited in how well it can track sleep, as it’s only looking at motion, not other biological signals like heart rate or brain activity. But I’ve found that its categories of “sound” or “light” sleep, while not perfectly scientific, correspond pretty well with my sense of how well I slept.

When I tested a more technologically sophisticated watch, the Basis B1, I found its sleep tracking to be laughably bad. At the same time that it documented that I woke up four times between dusk and dawn while dealing with a bout of food poisoning, it somehow classified that ordeal as a good night’s sleep.

Confessing My Sleep Struggles

When I first lost weight, I found that using MyFitnessPal to broadcast my weight-loss milestones to friends on Twitter was a very effective way of staying on track. So I’ve decided to shame myself every time I fail to get enough sleep.

Using a service called IFTTT, short for “if this then that,” I’ve connected my Jawbone Up to Twitter, and my Up wristband now tattles on me if I get less than seven hours of sleep.

So hey, take it easy on me, I only got 5h 3m of sleep last night.

— Owen Thomas (@owenthomas) June 11, 2014

It has some glitches. When I take an afternoon nap on the weekends, as is my wont, IFTTT misinterprets my short stint in dreamland as a catastrophic failure of somnolence. I haven’t figured out how to screen out these errant tweets, so I just delete them when it happens.

The challenge now is to take my sleep time from six hours—clearly too little—to the range of eight to nine hours that some recommend if you’ve hit a weight-loss plateau on a reasonably strict diet.

I could exercise what’s called good “sleep hygiene” and remove all the electronic screens from my bedroom.

But wait—if my phone’s in another room, how am I supposed to track my sleep?

Photo by Flickr user David Goehring