The International Computer Science Institute (ICSI), a non profit research organization in Berkeley, California, is due to present new findings next month regarding “cybercasing,” a word researchers coined to refer to how geotagged text, photos and videos (those that include location information) can be used by criminals and other dangerous parties to mount real-world attacks.

Using sites like Craigslist, Twitter and YouTube, the researchers were able to cross-reference information contained within publicly available online content to determine the exact home addresses of potential victims, even those who had posted the content anonymously. The experiments didn’t take weeks, days or even hours of research either – the addresses were pinpointed with GPS-level accuracy within minutes.

Consumers Don’t Know How Easily They Can be Found

The original report, “Cybercasing the Joint: On the Privacy Implications of Geotagging,” by researchers Gerald Friedland and Robin Sommer, was published in May and is due to be presented at the upcoming USENIX Workshop on Hot Topics in Security next month, reports trend-tracking site PSFK.

The report’s authors examined in detail the rapid spread of location-based services, which have spread in large part due to the growing smartphone market. Today’s mobile devices and their accompanying applications tap into a phone’s GPS or use Wi-Fi triangulation to append geotags, or locational information, to the items recorded with the phone, whether that’s an update posted to Twitter, a photo uploaded to Flickr or a video sent to YouTube.

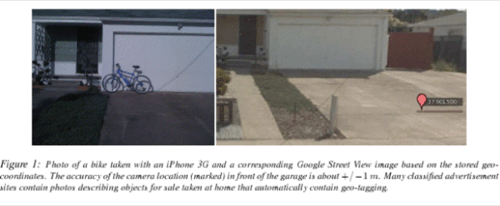

A major concern with these types of applications, say the researchers, is that many consumers don’t know such information is being shared, especially on a such a large, public scale. For example, Apple’s iPhone by default embeds high-precision geo-coordinates within all photos and videos taken with the internal camera unless explicitly switched off in the phone’s settings. The accuracy of these geo-coordinates “even exceeds that of GPS,” warn the researchers, regularly reaching “resolutions of +/- 1 m in good conditions and postal-address accuracy indoors.”

But publishing these precise geo-coordinates embedded into the shared texts, photos and videos to the Web is only part of the problem. Also troubling is the fact that the large amount of multimedia now available online combined with easy-to-use search tools for sifting through geo-tagged data makes it possible for anyone to easily launch systematic privacy attacks. In addition, services like Google’s Street View and other annotated maps help simplify the process of correlating findings across several independent resources.

In other words, it’s not just that the geo-tagged information is online, it’s that there are a plethora of tools with which to analyze it.

Cybercasing via Craigslist, Twitter, YouTube

To demonstrate the ease involved in determining a stranger’s precise location, Friedland and Sommer first “cybercased” Craigslist, a classified ads website often used to post items for sale. Here they found geo-tagged photos that they compared with Google Street View, allowing them to determine the postal addresses belonging to the item’s sellers. Even more helpful (if the researchers were, in fact, thieves), was that several ads included a “best time to call” – implying the hours the sellers were not at home.

In further tests, the researchers cybercased Twitter, which allows mobile users to geo-tag their updates. Third-party applications – like TwitPic, for example, used for posting images to Twitter – also include locational data. Using a Firefox Web browser plugin called Exif Viewer, it was only a matter of right-clicking on an image to reveal location of the Twitter post, plotted on a map.

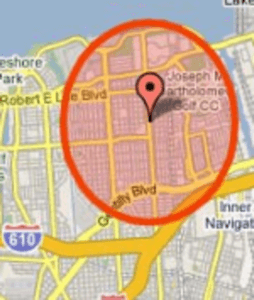

A third experiment, and perhaps the most devious yet, showed the ease with which this form of cyberstalking could be automated. While the above examples revealed users’ location within minutes, manual effort was still involved. For YouTube, however, the researchers wrote a simple script that automatically recognized when videos were recorded a certain distance away from a primary location, that being the potential victims’ home addresses. When the “vacation distance,” as it was called, was set to 100 KM, the script returned 106 hits revealing who was out-of-town in the test location of Berkeley, California. After briefly perusing the results, the researchers came across a video from someone who was clearly on a Caribbean vacation and would have made an ideal victim.

Solutions?

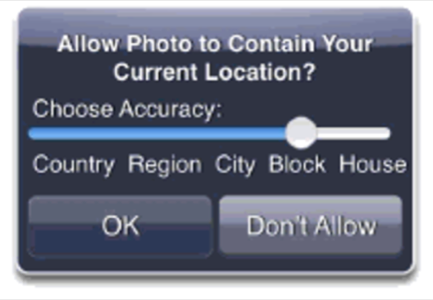

The paper’s goal was not to provide solutions, necessarily, for this digital era problem, but to raise awareness. Although the researchers did suggest a couple of interesting ideas, including a mockup of a mobile-phone dialog that would provide more control over geotagged photos and thoughts about privacy controls within APIs themselves, there aren’t any real-world fixes yet. For now, only user education and research into better systems for privacy protection is suggested.

But may we offer, perhaps, a simple fix to address some of these concerns: don’t post your vacation photos until after you return home and don’t Twitter about it while there. Simple steps like these could go a long way into protecting your home and valuables from being “cybercased” by any tech-savvy thieves.