The next time you pull out your smartphone and snap a photo of a landmark to upload to Facebook, think about the broader implications: Not only are you sharing your experience with your friends, but you’re contributing a small piece of data that could one day build a model of the world.

Researchers David Crandall of Indiana University and Noah Snavely of Cornell University are developing algorithms to create models of patterns based on the vast troves of photographs uploaded to Facebook, Flickr and other photo-sharing websites each day. Not only can their models be used to build 3D representations of a place, but they can also shed light on the people who visit those places.

“This analysis can also generate statistics about places, such as ranking landmarks by their popularity or studying which kinds of users visit which sites,” Crandall and Snavely wrote in an article that was published last month in the academic journal ACMQueue. “At a more local level, we can use automatic techniques from computer vision to produce strikingly accurate 3D models of a landmark, given a large number of 2D photos taken by many different users from many different vantage points.”

Crandall and Snavely suggest that photo-sharing sites can be used to model human behavior at given points in time and history. The implications are huge for marketers and could offer an explanation as to why Facebook has made a recent push into expanding its photo and mobile offerings.

There are, of course, limitations to the techniques, which will likely be overcome in time. Photo collections have an extreme scale and an unstructured nature, the researchers said; many different people take photos with many different cameras from largely unknown viewpoints, which complicates the ability to build the models.

Building 3D Models

The paper demonstrates how Crandall and Snavely were able to use 6,500 photos publicly shared on Flickr to build a computer-simulated reconstruction of Old Town of Dubrovnik in Croatia.

The advantages of using social media are clear: Such models can be built at a relatively low cost and don’t require costly site visits or surveys. The problem faced by the researchers is in developing algorithms that can extract useful data from the “noisy data” that flows through the typical API stream.

Mapping the World

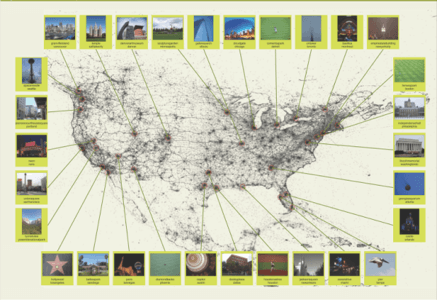

Most photo-sharing sites allow users to share more information than just the photo; the time and date a photo was shot, the location and even the type of camera used can be collected. Already, the researchers have been able to put together a list of the most-photographed places in the world (New York, London, San Francisco, Paris and Los Angeles round out the top five) and the five most-photographed landmarks (the Eiffel Tower, Trafalgar Square, Tate Modern, Big Ben and Notre Dame).

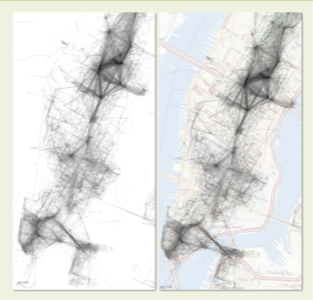

But the data can reveal so much more, including what types of people visit those places. Beyond that, algorithms are being developed that can effectively map how people travel through highly photographed places like Manhattan:

“We can infer a user’s social network with startling accuracy based only on such patterns,” the researchers wrote. “After observing that two people were at about the same place at about the same time on five distinct occasions, for example, the probability that they are friends is nearly 60%.”

To entice people to take more photos in places that aren’t photographed as frequently as, say, New York or Paris, the researchers have been experimenting with gamification. One such effort known as PhotoCity allowed them to collect 100,000 photos of the Cornell and University of Washington campuses by offering points to players who took photos at specific places.

“Imagine all of the world’s photos as coming from a ‘distributed camera,’ continually capturing images all around the world. Can this camera be calibrated to estimate the place and time each of these photos was taken?” the researchers concluded. “If so, we could start building a new kind of image search and analysis tool – one that would, for example, allow a scientist to find all images of Central Park over time in order to study changes in flowering times from year to year, or that would allow an engineer to find all available photos of a particular bridge online to determine why it collapsed. Gaining true understanding of the world from the sea of photos online could have a truly transformative impact.”