In the dead of night on Monday, November 14, Zuccotti Park in New York City was raided by police. In the preceding days, there were crackdowns at several of the major Occupy protests around the country. The effort had apparently been coordinated between cities. Monday night’s actions against the original Occupy Wall Street encampment were stern, heavy enough to bring a decisive end to the protest. But the raid only served to turn up the heat in New York and around the country.

As they have since the Occupation began, people on the ground fired up their smartphones to report the events as they happened, and curators around the Web gathered and retweeted the salient messages. But early on in the raid, mainstream media outlets began reporting that the police were barring their reporters from entering the park. The NYPD even grounded a CBS News helicopter. The night had chilling implications for freedom of the press. But the news got out anyway. The raw power of citizen media – and the future of news envisioned by a site called Storify – thwarted the media blackout.

Editor’s note: This story is part of a series we call Redux, where we’re re-publishing some of our best posts of 2011. As we look back at the year – and ahead to what next year holds – we think these are the stories that deserve a second glance. It’s not just a best-of list, it’s also a collection of posts that examine the fundamental issues that continue to shape the Web. We hope you enjoy reading them again and we look forward to bringing you more Web products and trends analysis in 2012. Happy holidays from Team ReadWriteWeb!

Saving The News

This is a new media age. The news of the Occupation has countless reporters, and some of the Web’s best curators have taken on the task of weaving the Occupy stories together. In particular, Xeni Jardin has been a machine on Twitter, providing a one-woman breaking news channel of so many successive Occupy confrontations.

But for the Monday night raid at Zuccotti Park, and indeed for much of the Occupation, Storify has come into its own as the social news curation tool par excellence. In fact, thanks to the media blackout Monday night, some of the most important news outlets in the country would not have had a story if not for Storify.

Josh Harkinson, a reporter for Mother Jones, crashed the barricades and reported from the scene, becoming a source for all the curators, including his own publication:

Storify’s New Role: The Backbone of News

“Most of the content comes from the people on the ground, from the 99%.”

Storify is one of those companies that arrives at its point in history just in the nick of time. Its co-founders pitched the idea during the Green Revolution in Iran, one of the first popular uprisings driven by social media. “Now it’s actually happening here, on the soil of America, with the Occupy movement,” says co-founder Xavier Damman.

The world needed a shareable, embeddable way to gather the tweetstorm of breaking news and turn it into a lasting document. Storify has made that possible. After a closed beta period with professional journalists, Storify opened to the public in April.

In October, it rolled out a brand new editing interface making the tool vastly easier to use. And one week ago, just before the police raided Zuccotti Park, Storify made its move, redesigning its homepage as a destination featuring the most important stories on the social Web. Storify’s vision is no less than a leveling of the media playing field. On the Storify homepage, lifelong and first-time journalists stand side by side.

“All news is social now,” says Storify CEO and co-founder Burt Herman. Whoever’s on the ground is the reporter, and whoever’s curating on the Web is the editor. It doesn’t matter who is whom. “We always talk about quoting from the original sources, from politicians, companies and everybody else, but now the journalists who are normally reporting are the sources.”

From a Dorm Room to the Front Page

While career journalists were being removed from Zuccotti Park, Ben Doernberg was watching the Web from his dorm room at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut. Ben is a college junior, and journalism is not his major. But his Storify of the Occupy Wall Street raid reached tens of thousands of people and was embedded by the Washington Post.

“This is not actually my first Storify,” he says, despite fun rumors to the contrary. “I was at Zuccotti Park about a month ago and happened to take a video that ended up getting on CNN, so this is kind of the second bizarre media day I’ve had in the last month.”

Doernberg used Storify to track the reports of the media blackout. “I looked at Twitter around 1 o’clock, and everything was going insane,” Doernberg says.

“By the time I decided to make a Storify, I had already read probably 100 tweets on this issue, so I tried to figure out what the overarching themes or the story seemed to be to me, and I went back through my memory of who tweeted what at what time.” What resulted was a comprehensive document of tweets, links, photos and videos of instances of the NYPD suppressing the media presence in Zuccotti Park. The Washington Post ran it, and the post has been viewed more than 20,000 times.

The 99% Media

The founders of Storify couldn’t be more delighted that students are making headlines using their platform. The day after the raid on Zuccotti Park, Storify shared two student stories from the raid on its blog. Doernberg’s was one. The other was by Columbia journalism grad student XinHui Lim, whose Storify post captured the grisly details from the ground and included embedded live-streamed video. At one point in the night, that amateur video stream had 23,000 viewers.

Damman says this is the perfect demonstration of the Storify redesign. These social media documents are the real story, and the NYPD’s obstruction of credentialed journalists only shows how out of touch the police are. “The police in New York don’t realize that it doesn’t matter to not have journalists on the scene,” Damman says, “because everybody is a reporter. What happened last night shows that they don’t get that.”

“Most of the content comes from the people on the ground, from the 99%.”

Herman agrees that Monday’s events prove that the distinction between legacy media and new media is no longer important. During the raid, journalists became sources, regular people became journalists, and they traded places with each other throughout the night. It’s all one medium now. “Let’s not spite the Internet,” Herman says. “Let’s let the Internet be what it is.”

The Gatekeepers

The NYPD’s censorship efforts were thwarted by smartphones, Web technology and good, old-fashioned gumption. But authorities are working hard around the country to block journalists from covering the Occupation. Twenty six reporters have been arrested so far, ten of them in Zuccotti Park on Monday night.

Fortunately, those incidents are being captured on Storify, too, and the curator wants to make sure the free press is protected.

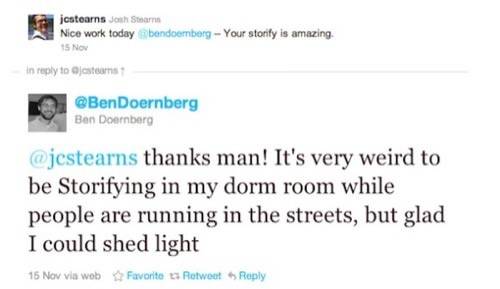

Josh Stearns, Associate Program Director at Free Press, has been storifying journalist arrests at Occupy protests since September. He’s using Storify as a living page, updating each time another journalist is arrested. You can help him by sending tips and tweets to @jcstearns.

Free Press is also holding a petition for their Save The News campaign urging New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg and the U.S. Conference of Mayors to stop attacking freedom of the press.

Watching the Story Unfold

November 15 was a big night for journalist arrests, and Stearns was watching Twitter closely. “I think of Twitter as the place where I watch the story unfold,” Stearns says, “but then I often look to a place like Storify or an article or liveblog where there’s somebody intentionally trying to contextualize and weave things together.”

One of the things Stearns struggled with during Monday’s raids was “that reports were coming in at all different times. Trying to piece together when something happened” was a challenge, since both the events and tweets about the events were displaced in time.

“Twitter’s so great for seeing the story unfold, but I think there’s a lot of awesome work that can be done in contextualizing it.” That’s where Storify comes in. “I think Storify is a very flexible tool, being able to do that kind of rapid reporting or to bear witness over time.”

Media Symbiosis

Stearns was impressed with Doernberg’s work Monday night and how Storify enabled it. “His Storify wouldn’t have been possible without people on the ground, and people on the ground weren’t able to get their story out until his Storify collected those from all over the place and broadcasted it, and that story got into the Washington Post.”

Storify provides the bridge between legacy and new media in situations like this. “I think there’s really nice symbiosis between the two,” Stearns says. “I think that’s one thing Storify has done really well, positioning itself within a new media realm but making new media approachable for traditional organizations.”

The Gatekeepers Are Changing

But legacy institutions aren’t weathering the transition well. The Associated Press came down hard on its staff for tweeting too eagerly about their arrests in an email that feels awfully shy about new media participation. It warns AP reporters not to get “caught in the moment.”

“If we’re having people who are non-traditional journalists doing critical reporting, and they’re getting thrown in jail because they don’t have the right press credentials, we need to figure that out.”

And law enforcement agencies seem to have little conscience about arresting journalists, even ones who are waving press credentials at them. Doernberg’s Storifycaptures two police officers replying “not tonight” and “don’t care” to protestations by journalists.

For Stearns, the important question is why. “The question becomes, were [the police] effective only to the point because they were only paying attention to one kind of media? And what was the intention behind that?”

“Why was there the decision to have a media blackout? Why were helicopters grounded? Why were journalists kept to the edges? If we ask those ‘why’ questions, and it turns out there was actual intentionality behind it, then that’s profoundly troubling.” If the police are really concerned about any message getting out at all, Stearns worries, they will learn to adapt to new media eventually.

Adapting To The New Reality

For some law enforcement agencies, that adaptation is already underway. “We’ve heard about Occupy protests around the country where they do strobe lights that actually blind camera phones and other kinds of cameras. Or things like the BART stations in San Francisco shutting down the cell networks when the protests come in.”

Law enforcement isn’t the only force that threatens freedom of the press. The technology companies who make the devices used by citizen journalists are a bottleneck for what kinds of reporting are possible. And many of the big ones have shown a disturbing willingness to comply with authorities.

“Whether it’s Amazon taking down all of WikiLeaks that was stored on their cloud servers because Senator Joe Lieberman asked them to,” Stearns recounts, “or whether it’s Apple and their patent for the camera [that blocks recording in designated areas], or Verizon blocking NARAL text messages, regardless of what issue it is, as the platforms change, the gatekeepers are changing.”

Taking Back The Media

Stearns sees hope in the way Storify and social media platforms have broken the police barricades around the media. “The one thing I think is really encouraging is that people are actually feeling ownership of their media,” Stearns says. “People feel like, ‘This is my phone. I’m creating my media on this.’ People want to take back the media.”

This is what the Storify founders have in mind. “This is a chance to create this whole new form of news,” Herman says. Storify held a gathering called Occupy The News at its San Francisco headquarters on November 7, where career journalists from a range of publications came together to discuss the possibilities of new media. You can soak in their insights – where else – on Storify.

A tumultuous time like ours is ripe for a disruption of the ways in which we capture our stories and work toward the truth. The gatekeepers are changing, but the media are changing faster. There have never been more ways to experiment with information. Thanks to platforms like smartphones, Twitter and Storify, the barriers to participation are vanishing.

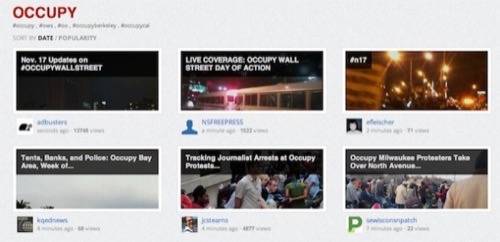

You can see all Storify posts about the Occupation on the occupy topic page.

Check out our guide on How To Curate Conversations With Storify.

Sign the petition to Save The News.

Have you ever used Storify? Share your posts in the comments.