Point-and-shoot cameras have been a hit with consumers for more than a century, and they keep getting better. But it doesn’t matter, they’re doomed anyway. Even awesome image quality and all the features in the world can’t save them from the mighty smartphone.

The Basics

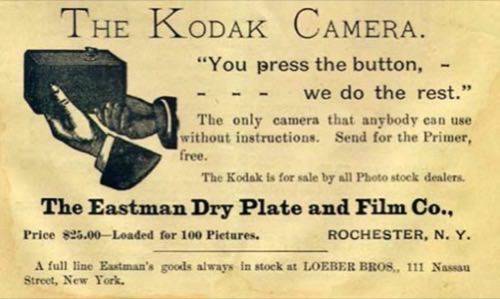

“You press the button, we do the rest.” In 1888, with that tagline, George Eastman released the portable Kodak camera, and consumers have been snapping pictures with point-and-shoot devices ever since. In 1900, he released the Brownie, a cheaper, even simpler camera that would define point-and-shoot photography for almost 60 years. Over time, consumer cameras evolved, moving to cartridge-based film, then to digital. They added zoom lenses, digital viewfinders, video recording and Wi-Fi. Still, they never lost their focus on simplicity and functionally. When you down to it, a Canon PowerShot isn’t all that different from a turn-of-the-century cardboard Brownie. Simple plus portable equals mass adoption, and that equation worked for more than 100 years.

The Problem

First, let’s be clear about definitions. When we say “point-and-shoot” cameras, we’re not talking about digital single lens reflex devices (DSLRs), mirrorless cameras, or any other device with interchangeable lenses. We’re talking about dedicated, autofocus, fixed-lens cameras that generally fit in your pocket, like the Canon PowerShot, Sony CyberShot, or Nikon Coolpix – also called “Compact Digital” cameras.

The issue is that point-and-shoots are caught between a rock and a hard place. They can’t match the quality and flexibility of DSLRs, and they can’t match the cost and convenience of the cameras included in every smartphone.

Point-and-shoot quality keeps getting better, but it will never match the quality of an equally modern DSLR or mirrorless camera. There are several reasons, but the most obvious is the lens. A large, fast and appropriate lens gives a sensor more to work with, and that will never change.

But with point-and-shoots, beyond a certain threshold, quality was never the point. These days, few photos actually make it to print. Most pictures wind up on Facebook or a desktop background, and your average point-and-shoot camera packs enough pixels to print 5x7s or 8x10s of your best shots. And for most people, “good enough” is all that matters.

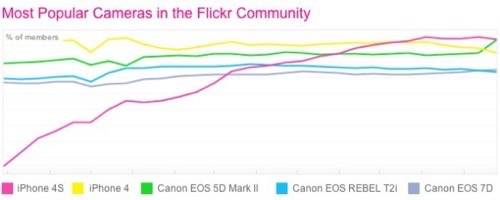

The real issue, though, is that smartphone cameras are also increasingly “good enough.” In fact, the iPhone 4 is apparently good enough to be more popular than any point-and-shoot camera on Flickr, and the iPhone 4s is more popular than any other camera, including DSLRs. Sure, this is because of a massive distribution advantage over dedicated point-and-shoots, but that’s the point. They’re good enough, and everyone already has one, so why buy (and carry) a second device that’s only marginally better, and far short of a pro-style DSLR model?

To some, the answer is “optical zoom,” the dedicated camera’s biggest advantage. Smartphone cameras, by contrast, have to get by with so-called “digital zoom,” which basically means “cropping.” Others require better performance in low light, or other special features.

But their numbers are limited, and high-end smartphones keep closing the gap.

The the Nokia 808 can now produce 41 megapixels, far more than most consumers need, giving a lot of room for digital zoom while maintaining acceptable quality.

And smartphone makers are all working to improve camera performance – especially in low-light conditions where their tiny lenses suffer the most. Electronic trickery like Nokia’s PureView oversampling, for example, helps compensate for poor image quality. Take a look at the commercial above, shot on the Nokia 808 it’s advertising. That’s definitely “good enough” for the vast majority of users.

The Prognosis

Smartphone camera sensors and software that have already reached an acceptable quality threshold will continue to get better. And low-profile, lower-power smartphone optical zooms are in the works. So for the mainstream audience, dedicated point-and-shoot cameras will go the way of PDAs.

Some households will still want a better camera for portraits, vacations and other must-capture events, but with prices for prosumer-level DSLRs dropping, there’s won’t be much reason to settle for a point-and-shoot when quality is at stake.

Can This Technology Be Saved?

Sure, there will always be some people who want a pocket-sized camera with a fixed optical lens and a big battery. And camera companies will continue to pump out new and better examples. Some will even run Android, like the Coolpix S800c, or even have built-in phone functionality, like the Polaroid SC1630. But point-and-shoot is already becoming a niche, not the mass market, and it will take an unforeseen, revolutionary breakthrough to change that.

Previous Technology DeathWatches

Video Game Consoles: The utility of bundles apps like Netflix and Vudu seems to be slipping. NPD Study showed that one in five consumers who view streaming video on their TVs do so without a peripheral device.

QR Codes: It’s been a mixed bag. While B of A is testing QR codes for mobile payments (good news for the technology), a security researcher demonstrated how a malicious QR code could be used to wipe a Samsung smartphone.

Blu-Ray: The same NPD study reveals that “online video is maturing” as users migrate to watching streaming media on their TVs.

Company Deathwatches

For an update on our baker’s dozen of company Deathwatches, check out ReadWriteWeb DeathWath Update: The Unlucky 13.

Generic camera image courtesy of Shutterstock.