ReadWriteBody is an ongoing series where ReadWrite covers networked fitness and the quantified self.

I am keenly aware of the blister on my left middle toe. It would probably heal better if I didn’t insist on walking 10-plus miles a day.

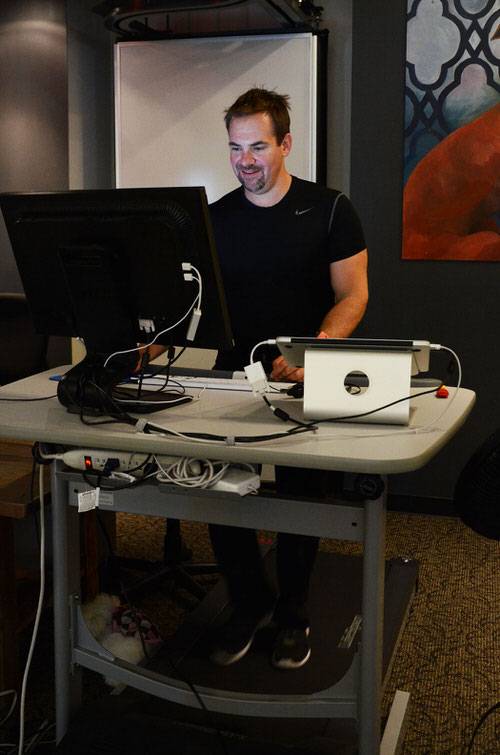

For a couple of weeks now, though my coworkers and I agree that it feels much longer, I’ve been spending most of my workday walking 3 miles an hour on a treadmill desk.

Why? It’s part of a four-month experiment I’m conducting on myself. I’m starting by trying to drop some weight—20-plus pounds by December—while getting into measurably better shape.

“Measurably” is the key word here. The quantified-self movement is a catch-all term for the efforts to better understand the human body through data. I can’t call this a perfectly scientific experiment, since I’m running a sample set of one and there are far too many variables to control.

But part of the point of using treadmill is just putting down numbers—pushing myself further than I’d go in an ordinary day to see what happens.

Walking For A Living

The first question: Can I do my work? The answer is yes—and far better than what I’d read suggested I could do.

Most treadmill-desk write-ups recommend going 1-1.5 miles per hour, and some users report they can’t type at faster speeds than that.

Redmonk analyst Stephen O’Grady confirmed this in his experience with a treadmill desk: He had to hop off to write longer pieces, and even email was easiest at less than 1 mile per hour. Two colleagues who tried the desk agreed: They needed to slow down to type. So O’Grady’s experience may be typical.

Yet I’ve actually managed to write entire pieces—like this one, and the previous installment in ReadWriteBody—while walking at 3 miles per hour. (The treadmill’s maximum speed is 4 miles per hour, which is too fast for comfortable typing in my experience.)

I may well be an outlier here in my ability to adapt to working while walking. I credit the high-school instructor who taught me to touch type. I could already carry on a conversation while typing without looking at my keyboard, so on the treadmill, I don’t need to look down at the keys.

If you’re constantly glancing at your keyboard, that likely throws off your balance. Your mileage may vary—I’d recommend going slow and then seeing how fast you can go.

Can You Hear Me Now? How About My Treadmill?

For phone calls, my conversation partners didn’t report hearing noise from the treadmill or my footstrikes. When I did a Google Hangouts video chat with colleagues, though, I found that the constant motion was distracting both to them and to Google’s motion-detection algorithms, which often threw the screen focus to me even while someone else was talking—so I turned off the camera except for when I was talking.

The biggest drain to productivity has been the position of the treadmill in our open-plan office: I’m on the way to the kitchen, and it’s highly visible, so curious coworkers have come by to ask questions. (Mostly they ask if I can really type while walking. I’ve shown them drafts of this piece by way of reply.)

Connect Me, Connect Me Not

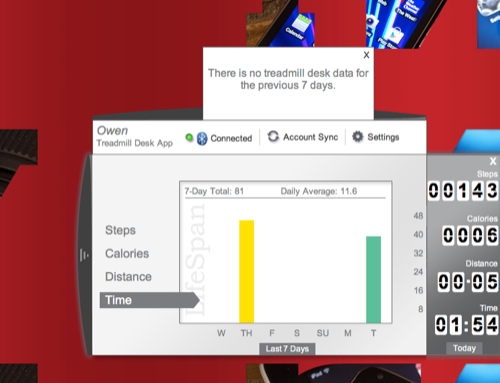

The LifeSpan Fitness TR1200-DT5 has good basic controls. You can enter your weight, which helps it estimate calories burned. It also tracks time spent, steps, and distance.

It also has a companion website and downloadable desktop software which ostensibly connects to the treadmill via Bluetooth. I say “ostensibly,” because I only managed to get the treadmill to communicate data to the desktop app and hence to the website twice. After the first day, it claimed to be syncing with the Lifespan website; after a week, the desktop app stopped connecting with the treadmill’s Bluetooth connection altogether. Just yesterday, it started working again. A LifeSpan support technician was not able to diagnose the problem.

Which is just as well, because the Lifespan website and desktop app are both useless and ugly. Even if they functioned as advertised, I wouldn’t want to use them.

I’m not alone. O’Grady, the Redmonk analyst who has a similar LifeSpan model, came to a similar conclusion. He thinks LifeSpan should stick to making fitness hardware, and leave software to other people.

“I don’t trust [LifeSpan] to do software,” O’Grady said. “I can’t get the data out of it where I want to.”

It’s frustrating that I can’t use the treadmill desk’s Bluetooth connection to connect to, say, the MapMyFitness app on my smartphone, which already collects similar data from the EB Sync Burn fitness tracker I wear. The tracker and the treadmill disagree on the number of steps I’ve taken—here, I trust the treadmill’s data, but I have no good way to reconcile them in one cloud-based store. O’Grady says he uses a Google Doc to log his miles. I just tweet them at the end of the day.

It highlights a problem ReadWrite contributor Matt Asay recently wrote about: our quantified-self data is stored in a bunch of unconnected silos.

The one aspect of the hardware I’d complain about is the emergency stop cord, which LifeSpan tells me is required by regulations. When I did a video chat, I found myself leaning in to better position myself in front of my laptop’s webcam, knocking the cord loose and bringing the treadmill to a halt. Every time I did this, the treadmill also lost all the data for my session to date.

A LifeSpan spokesperson told me that safety rules require that the system cut off electricity when the cord is pulled, but it seems like LifeSpan could correct this problem with a tiny, cheap memory chip that retains data when the system loses power. (The Bluetooth connection seemed noticeably more erratic after I accidentally triggered the stop cord, though I’m not sure if the events were connected.)

My Blistering Pace

So what’s it like walking all day? It’s easy on my back and neck, which seemed to suffer from sitting. But it’s rough on my feet—I feel sore to the bone, and there’s the blister I mentioned, which I probably could have avoided with more cushioned socks.

And then there’s the sweat. When I first got the treadmill desk, I didn’t have a fan, and I went through three T-shirts in one day. Even with the fan, my boss took a look at me one day and said, “You need a shower.” Luckily, our office has one built in.

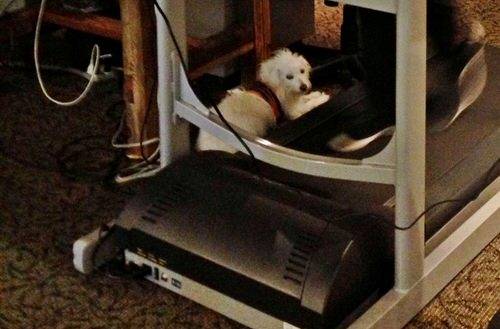

I won’t lie: I’m tired. I’m probably, relatively speaking, overdoing it, clocking an average of 10 or more miles per day. But I’m already pretty fit—I frequently walk my dog, Ramona the Love Terrier, up the Filbert Steps and around Coit Tower, a vertiginous climb even in our hilly hometown of San Francisco, and I often walk from North Beach to our office in the city’s SoMa neighborhood.

So part of the test for me is not whether I can add a little bit of activity to a sedentary lifestyle, but if I can actually push my levels of performance and effect changes in my metabolism and body competition. And, yeah, fit into that pair of jeans at the bottom of my chest of drawers I’ve been avoiding.

So far, so good: I’ve dropped six pounds in a little less than two weeks. That’s not the only metric I’m measuring, but it’s a useful data point.

Correction: The model I tested is the TR1200-DT5, not the TR800-DT5. Apologies for the error.

Are you quantifying yourself? Share your experiences in the comments or on Twitter with the hashtag #rwbody.