I’m not one of the people that thinks that “private cloud” is an oxymoron. But vendors that are trying to offer self-hosted alternatives to Google App Engine, Amazon Web Services, Heroku, and the rest need to understand that cloud deployments are supposed to be about reducing friction of deploying and running services. That includes the friction of having to deal with undisclosed pricing and sales pitches that enterprise software has been saddled with for way too long.

One of the things that I really like about providers like Amazon and Heroku is the simplicity of dealing with their service. You check out the sites, evaluate the pricing and test out the free tier to see how it handles. If all goes well, it’s time to start putting services into production.

The downside to Heroku and AWS, of course, is that you’re running on someone else’s architecture. There’s a legitimate demand for private PaaS and IaaS services, and more and more vendors are trying to elbow their way into that business. The problem is that some of the new entrants are hoping they can continue using the old and busted enterprise pricing models.

The excuse for not providing pricing in most cases boils down to complexity. Vendors say that pricing is too complex to disclose because it depends on too many factors. If that’s the case, I’d recommend two things. First, simplify your pricing structure. Second, provide a baseline or some sample scenarios so that customers have some idea what they’re getting into before having to engage with sales.

In the past two weeks, I’ve had run-ins with vendors that completely refused to disclose any real information about their pricing. And this is after one vendor promised during a briefing to provide pricing after the call, and the other weaseled out of providing pricing info after being told it was a condition of my taking the briefing.

Vendor one sent this follow-up, in lieu of pricing: “[product name] pricing is based on a number of factors. The bottom line is that it’s priced to be comparable to what a company would pay to have their own people run it in-house, but in addition, you get the power of [company identifying slogan redacted] and a team of cloud experts with years of experience running one of the largest clouds in the world…” In other words, it’s too complex.

Complexity is No Excuse

The excuse for not providing pricing in most cases boils down to complexity. Vendors say that pricing is too complex to disclose because it depends on too many factors. If that’s the case, I’d recommend two things. First, simplify your pricing structure. Second, provide a baseline or some sample scenarios so that customers have some idea what they’re getting into before having to engage with sales.

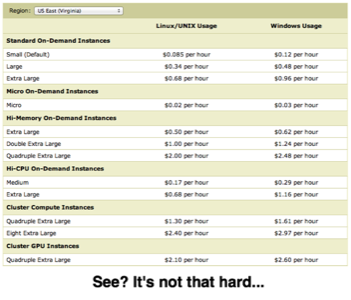

If you look at Amazon’s pricing, though, you see what a sham the complexity excuse is. Amazon’s pricing just for EC2 depends on how many instances you’re running, what type of instances, whether you commit to a certain number of instance hours and a number of other factors. Bottom line, though? Amazon’s pricing is fairly transparent.

That doesn’t prevent Amazon from having variable pricing for volume customers. If you want more than 500TB of data transfer per month (for example) Amazon directs you to its sales folks. But customers have a pretty good baseline of what Amazon’s pricing is. There’s room for negotiation and volume discounts, without leaving customers clueless. Convirture is another example. Their pricing is variable but they at least provide a starting price that gives customers something to start with.

Why so Secret?

“It’s the old ‘how much is it? Well, how much do you have in your pocket right now?’ game. Customized pricing cuts both ways.” – Evan Schuman

As fellow RWWer David Strom says, priceless is not a marketing strategy. Wrong pricing, says Strom, “can turn the most amazing product into a dog, and not putting the pricing online… just makes everyone more frustrated and the chance to lose a customer to a competitor, where this information is clearly stated.”

Just why are vendors so secretive about pricing? It might not be because the pricing is too high. Evan Schuman, editor at StorefrontBacktalk.com, says “it’s just as often a fear of the price being too low. For a certain prospect with a certain budget, the vendor might be able to charge more. It’s the old ‘how much is it? Well, how much do you have in your pocket right now?’ game. Customized pricing cuts both ways. Yet another reason to insist on meaningful numbers.”

No Pricing, No Story

As is happens, I do insist on meaningful numbers. Without some hard pricing information, and not just a handwavy “pricing is variable” I’m not covering the product or service, period.

It turns out, I’m not the only member of the tech press with this policy. In polling other folks, like Schuman, I found universal agreement that pricing is almost always a requirement for a story. Pam Baker says, “readers who are interested enough to read a particular review or product story want to know the price. So, if a vendor refuses to disclose pricing, or at least a pricing range to cover the various purchase options, then I either won’t cover the product at all, or I’ll note to the reader that the undisclosed price is probably kept secret because it is way too high.”

Of course, there are some exceptions to the “no pricing, no story” rule. When companies announce a product in development, it’s not uncommon that pricing isn’t set. When you’re a long way out from the supported offering, it might still be newsworthy.

But when something is going from a closed beta to general availability, as was the case with the vendor that weaseled out of pricing information, there’s no excuse. It’s one of the first questions that the customers are going to ask, and it belongs in any news coverage of the offering.

Cloud vendors that want to compete with AWS, Heroku, Engine Yard, Google, and the rest need to bring their pricing practices into this century. Had problems with vendors and pricing? I’d like to hear your stories in the comments.