Quite a few people have been retroactively credited with the invention of the personal computer. One man who never claimed credit himself, but who would certainly be listed among Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, Clive Sinclair, Adam Osborne, and John Roach as original creators of the personal computer industry is Jack Tramiel – who passed away today at the age of 83.

I’ll call him Jack, for reasons I’ll explain in a bit.

His Commodore Business Machines was already a two-decades-old firm, and perhaps the first retail manufacturer of pocket-sized calculators (there’s conflicting evidence), by the time he conceived a way to sell fully functional personal computers.

In 1976, Jack didn’t just buy MOS Technology’s 6502 microprocessor (based on Motorola’s 6800), he bought MOS Technology itself, along with its creator, the legendary Chuck Peddle. That purchase led to the creation of the Commodore PET (Personal Electronic Transactor), and if you still think Steve Jobs invented the personal computer, realize that Jack’s acquisition of MOS made Jobs’ and Woz’ design decisions possible.

One of my first personal computers was a Commodore PET 2001 which, despite the numeral, was actually made in 1977. It was an early edition, meaning it had the “Chiclet” keys rather than the standard keyboard layout, produced by Commodore’s calculator division back before full QWERTY-style computer keyboards became marketable.

The PET 2001 is as indicative of Jack Tramiel’s personality as anything he or any of his companies would ever produce. I still have my old PET, and last I checked, it still worked. It had a steel case like a microwave oven and a shape like some “Mr. Computer” character in a children’s TV show, with a tapered roof for the screen that seemed to merge Napoleon’s hat and the old NET TV logo. It had 8K of RAM, which I leveraged to create a lunar lander game (for the 10th anniversary of Apollo 11), a MasterMind game (guess the four-digit sequence) and an American History quiz generator.

I pitched all of these to Commodore at one time or another, for distribution through its software channels. (You could mail-order a program, and it would come to you on a cassette tape – an ordinary audio cassette – in a plastic bag.) While my pitches were all rejected, the rejections came on formal business stationary signed by human beings.

This was how a Jack Tramiel company did business. He was perhaps the first businessman to understand the personal computer business as just another business, another way to access the customer. And as just another businessman (which is what he truly was, and would want to be remembered as), he knew how to build relationships with customers, with suppliers and with supporters.

Jack and his sons, Gary, Sam, and Leonard – all of whom were involved in the family business – were perhaps the most accessible executives of any computer company I’ve ever encountered. In my first escapades as a correspondent covering the computer industry, I’d call up the company and leave my name with a secretary – not a PR person, but a real secretary. And in a half-hour or so, I’d get a call back from one of the Tramiels, and we’d spend a another half-hour discussing everything I needed to understand about the way business works. Here I was, perhaps the only serious writer in the business with a 405 area code, getting same-day callbacks from a CEO or president or executive VP.

Every die-hard computer programmer of the early 1980s was a loyalist to one brand or another. I was an Atarian. When the Commodore 64 – which I rejected as an Atari 8-bit ripoff – became the best-selling computer in history, the reason was because the Tramiels were better businesspeople. The C64 wasn’t really a better computer, but it wasn’t bad, and it sold for a better price point. It had a better software base, and was visible through more retail channels. No other businessperson in the 1980s could have pulled off the C64.

So even though the Tramiels were the “opposition” I could share my feelings openly with them, and they’d be happy to argue with me. Usually Leonard, though more than once Jack joined in shouting talking points into the speakerphone.

All this changed in 1984, when the Tramiels exited Commodore, purchased my beloved Atari, and built Atari Corp. Perhaps the reason I got my first regular column at an Atari magazine called ANALOG Computing was because I could get a Tramiel on the telephone.

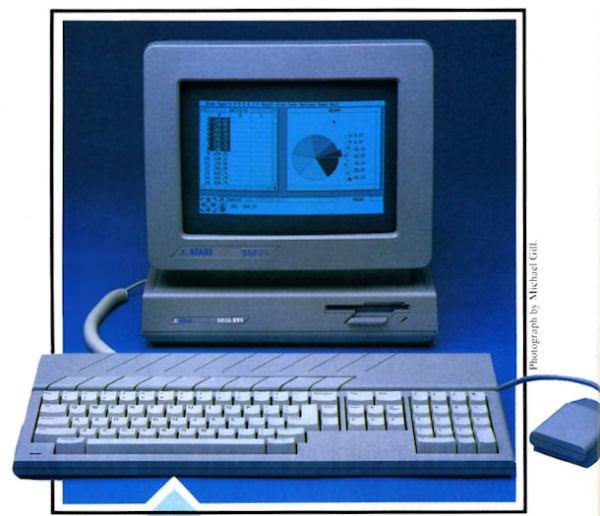

The Tramiels wanted to produce a new 16/32-bit architecture machine called the Amiga. It was no secret, because the Tramiels kept no secrets – whenever they decided to do something, step one was to put out an announcement. When Commodore scooped up the Amiga instead, Jack and Sam Tramiel tasked former Commodore designer Shiraz Shivji to break out a back-drawer design for something they wanted to do at Commodore – a business machine capable of doing Macintosh-style graphics in color and, of course, for less money.

The Atari ST was a brilliant device, and the focus of about five years of my working life. Based on the same Motorola 68000 chip that ran the Mac, it enabled families to purchase a complete computing system with a working laser printer for less than $1,000. Compared to anything else built at the time, including the IBM PC AT, it was supremely fast at number crunching. Nicknamed the “Jackintosh,” it wasn’t much of a secret that “ST” didn’t really stand for “sixteen/thirty-two” but for “Sam Tramiel,” just as the “busy bee” icon was essentially the family crest, the Polish “trzmiel.” (Born in Poland in 1928, Tramiel survived Auschwitz, and emigrated to the U.S. after the war.)

The ST was not a ripoff of the Macintosh or the Amiga, though it did attempt to capitalize on their success of the former. But while it had the most innovative hardware of its day, it struggled against the notion that better hardware was just around the corner – a notion put into buyers’ heads by the Tramiels themselves, who never could keep quiet about what was to come later. Unfortunately, what was to come sometimes never came at all.

Other times – the Atari TT and the Jaguar, for example – it came way too late to make a difference. Jack Tramiel played by an old set of rules that was perfectly legitimate, honorable, and competitive for an earlier era. When Apple changed the game, the Tramiels didn’t change with it.

And that’s a shame, because Jack Tramiel’s stubbornness has kept him from his rightful place among the giants who helped create the personal computer.

The PET 2001, the Commodore 64, and the Atari ST are three of the most important consumer products ever produced. Although only one was a huge financial success, the way you use your PC and your tablet and your smartphone all depend on the paths blazed by those three devices. Jack was the rare tech-company leader with true retail consumer product experience. He didn’t invent anything, but he set many of this industry’s wheels in motion, and we all owe him a huge debt for doing so.

Commodore PET 2001 photo courtesy Old-Computers.com