PayPal and Stripe are in a knock-down, drag-out battle for every big e-commerce app’s business.

So on some level, it wasn’t surprising to see both Stripe and PayPal’s Braintree unit involved in Pinterest’s new Buyable Pins feature, which will soon allow iPhone or iPad users to click a “Buy” button when they spot an interesting product on the visual discovery service.

But it is when you dig past the surface—and learn that this isn’t how Stripe and Braintree, which provide payment services and software tools that let developers include them in apps and websites, normally work.

See also: Pinterest Announces Buyable Pins And A Partnership With Stripe

“The foundation for Buyable Pins has been built with industry-standard practices (in terms of the vault, gateway and processor, and the ways in which customers and merchants will interact with the providers),” Malorie Lucich, a Pinterest spokesperson, wrote in response to ReadWrite’s questions on its relationships with Braintree and Stripe.

In reality, very little was standard about Pinterest’s Buyable Pins, and Pinterest expended considerable time and effort to convince Stripe and Braintree to work with it in ways they do not currently work with other customers.

For one thing, Stripe and Braintree rarely cohabit in the same app. Developers normally pick one and stick with it. (A rare exception is Lyft, the ride-hailing app, which uses Stripe for most transactions and Braintree for customers who want to charge rides to their PayPal accounts.)

No Payments Down

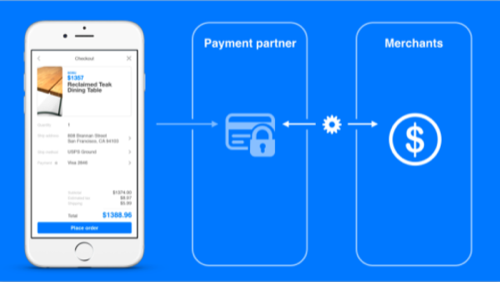

The other odd thing about Pinterest’s relationship with these payment companies is that, well, there aren’t any payments involved. At the launch event for Buyable Pins, Michael Yamartino, the product manager leading Pinterest’s push into e-commerce, confirmed that Pinterest is not the “merchant of record” in transactions that happen through its app.

In other words, you won’t see a charge from Pinterest on a credit-card statement; the charge will come from the retailer, even though you’ll never visit the retailer’s website or mobile app in the course of making a purchase on Pinterest.

Unlike normal Stripe and Braintree customers, Pinterest doesn’t have a processing relationship with either company. Purchases are charged directly by the retailer’s existing processor. That might be Stripe, that might be Braintree—or it might be a host of other companies which offer online credit-card transactions.

Pinterest is using Braintree and Stripe merely to “vault,” or securely store, cards. That accomplishes two things: Pinterest doesn’t have to be in the risky business of storing card numbers, but it can still stash those details for future purchases, so Pinterest users don’t have to reenter their card numbers every time they click a Buy button.

Go On And Make That Money

Why does this matter? Because Stripe and Braintree make money by processing transactions. Vaulting credit cards, supporting alternative payment methods like Apple Pay, and detecting fraud are all bells and whistles they provide in exchange for the right to take a cut of the transactions they handle. Both payment processing services charge a standard rate of 2.9% plus 30 cents per transaction—so they compete mostly on the additional services and support they offer.

At launch, merchants who want to put a Buy button on their Pinterest pins need to work with Shopify or Demandware, two big e-commerce software providers. Stripe and Braintree are both options for Shopify customers, but the company supports many others. Demandware likewise works with a host of partners. (PayPal is listed as an authorized Demandware technology partner, while Stripe isn’t, though Spring, a Demandware services partner, works with Stripe.)

When you click a Buy button on Pinterest, your card might get handled initially by Braintree or Stripe, and stored on one or the other company’s servers for future purchases. You’ll have no way as a consumer of knowing where it is; Pinterest is asking you to trust that it’s stored with one of the two companies, which are both in the business of keeping financial transactions secure. That card will get passed on to a merchant’s processor, who, we’ll point out again, might be Stripe, Braintree, or anyone.

It’s not clear if Pinterest pays anything for the vault-only service. None of the companies involved would comment on terms of their agreements. But two sources ReadWrite spoke to confirmed that it was not a standard offering, and that Pinterest spent considerable time convincing the companies to offer the vault-only service in order to be included in the launch of Buyable Pins.

Pinterest is not charging any fees to merchants or consumers for buying through Pinterest. Instead, it hopes to make money when retailers buy ads to make their pins more prominent on the service, according to Joanne Bradford, Pinterest’s head of partnerships. Since Pinterest isn’t getting a cut of the purchases, it’s hard to see the company paying out any kind of fee to third parties for facilitating those sales.

It seems like a Pyrrhic victory. Both Stripe and Braintree get to claim they’re involved with Pinterest’s venture into e-commerce. But according to all the indications we have, any money they make from this deal will be all but accidental—if the item a user purchases through a Buyable Pin happens to be sold by one of their customers. Pinterest has no way of guaranteeing that.

Spreedly, a two-year-old startup based in Durham, North Carolina, does offer card vaulting as a stand-alone service. It charges marketplaces and other customers $99 to $3,000 a month. Spreedly customers can take a securely vaulted card number and pass it on to any number of payment gateways.

(A note on terminology: Gateways handle the technical side of moving payment data, while processors move the money. Companies like Stripe and Braintree typically fill both roles, while other players may act as just a gateway or just a processor. Quora has a deeper discussion of these roles.)

A Sign Of Things To Come

While Pinterest’s deals with Stripe and Braintree are very much a departure from business as usual, it may be a harbinger of things to come, Spreedly CEO Justin Benson says.

He says his startup is having conversations with lots of players interested in facilitating retail transactions, but without taking on the burden of being the actual seller of goods.

“When you talk to these companies, the initial response is, ‘I’ll just partner with Stripe or Braintree, and everyone who wants to sell through my platform will set up an account with Stripe or Braintree,'” says Benson. “They quickly realize that the sellers have their existing providers.”

In the long term, this may force Stripe and Braintree to change their business models. The warring payments businesses compete on the completeness of their feature set and the ease of building their code into an app. They’re rewarded by the transactions that flow through their networks as a result.

That works for companies like, say, Uber or Airbnb, who want to be the brands that show up on a customer’s monthly statement. But for social apps like Pinterest, which wants to facilitate commerce without actually putting its name behind the transaction, the current model for payments may not work.

Benson says Spreedly designed its pricing to avoid charging a per-transaction fee intentionally; instead, it charges on a sliding scale typically based on the number of cards it stored. If Stripe and Braintree decide to commercialize the one-off service they’re providing to Pinterest, that’s not a bad model to follow. It’s an open question, whether it will be as profitable as the traditional way of making money from online payments, though.

Lead photo courtesy of Shutterstock; diagram via Pinterest Engineering