The definitive dictionary of the English language, the Oxford English Dictionary, may well never see the light of day again, only the light of a monitor. Nigel Portwood, chief executive of Oxford University Press, which publishes the OED, told the London Sunday Times that dictionaries sales have been falling off at a rate greater than 10% a year for the last few years. So the next edition may be online only.

Such a move might be financially reasonable. After all, the current online edition gets two million hits monthly at $400 per user, and more people are favoring compact, universally-retrievable sources of information. But is finance all we should consider?

Over at GigaOm, Matthew Ingram asks if we should care. His response, if I’m reading him right, is yes. I yearned for an opportunity to disagree, dramatically, just pro forma. But I can’t. I’ll go into a bit more detail on why a “hardcopy” of the dictionary (I favor the neo-logism, “book”) is still desirable.

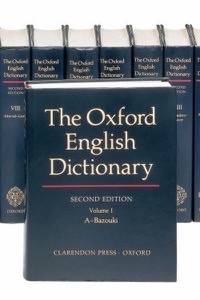

The idea of small, lightweight, online, retrievable sources of reference materials is fantastic. I use Dictionary.com more than I use my Websters. (Though Websters gets money either way.) So why not the OED? After all, the twenty-volume mega-book is, at almost $1,600 hellishly expensive and, if you’re sub-Ferrigno, immovable.

Because while some books are repositories of information, others are experiences. Although the OED is not a narrative, not scripture, not poetry, it is, nonetheless, transportive. The idea of flipping from one entry to another, following a line of inquiry (especially etymological inquiry) from one page to another, even one volume to another, is a sensual experience. I don’t mean it’s sexy (it is), but rather that it’s an experience that encompasses sight, sound and touch and even hearing (the rustle of pages, the thump of the volume hitting the desk) to create the context for comprehension.

I agree with Matthew that it doesn’t need to be a commercial production, with loads of books run out and sent by plane and truck to book stores. It may become something of a bespoke tradition – created at user request. Although the Oxford University Press said it hadn’t made a hard-and-fast decision as to whether they’d print again (the next edition probably won’t be ready for a decade), they should make a hard-and-fast decision never to stop printing, even if they have to change the way they print.

If scifi has been in some way a guide to our future, let’s remember that Picard read manifests on a PADD but Shakespeare in a book; and further, each new technology does not push all previous technologies out. Nor should it.

So come on, Nigel. Make a commitment. Give us that sweet must of a real book when we need the experience of language, not just the data.

What do you think? Does the Book matter, or is it only a vehicle for the experience of reading?

For more discussion of the online reading experience, read Richard MacManus’s posts where he examines the pros and cons; and mine, where I ask whether e-books are the new paperbacks.