In much the same way that new technology made it possible for many to recreate digital versions of ancient worlds, the manuscripts that explain those worlds have also gone online. Once upon a time, not long ago, if you wished to see an important document, letter or codex, you had to visit the institution that held it. That meant, for all practical purposes, you had to be rich, or a professor. No longer.

Like my earlier survey of those virtual ancient worlds, this is a mere sample of digital manuscripts available online. But maybe it will be a good place to start. Although no more than a fragment of all institutionally-held documents are online, it is a trend unlikely to reverse. You’ll be busy enough just with these.

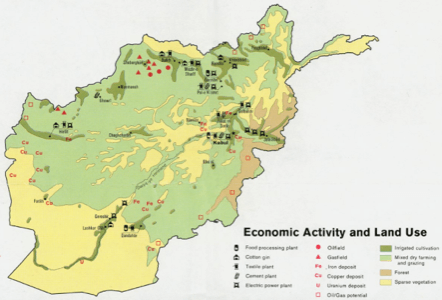

Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection

The first ever collection of digitized manuscripts I ever saw online was also the first one I ever used. The University of Texas library system digitized its vast map collection. The collection spans historical maps, political maps through time and maps based on topics like agriculture. The librarians and staff in charge of the site also kit out the home page with maps of topical interest, such as Afghanistani and Iraqi maps and maps of the BP oil spill. The latter includes links to the maps of other organizations, such as newspapers, curated by the staff.

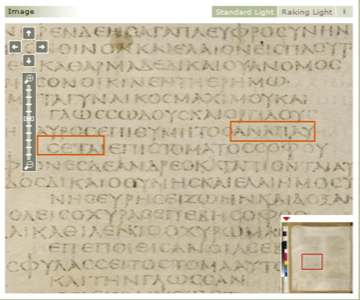

The Monastery of St. Catherine at Sinai: Codex Sinaiticus

The Monastery, among other things a library of long standing, has a pretty complete website. But to present and share one of its most important books, the Codex Sinaiticus, it has partnered with the British Library, Leipzig University and The National Library of Russia. The whole codex, a book that contains “contains the earliest complete copy of the Christian New Testament” in addition to the Septuagint (Old Testament). It has also been heavily annotated by early students of the Bible.

I had the good fortune to see the codex at the British Library and of that experience I have only this to say: squeeeeee!

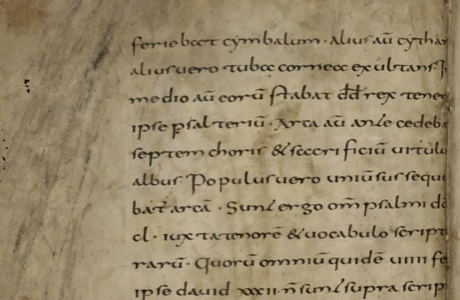

The University of Fribourg’s ambitious goal in creating this site is to “provide access to all medieval and selected early modern manuscripts held in Switzerland via a virtual library.” The winner so far is the Abbey of St. Gall, contributing 403 of the 649 manuscripts digitized to date. This is not surprising as it’s the largest, oldest library of its type in the country.

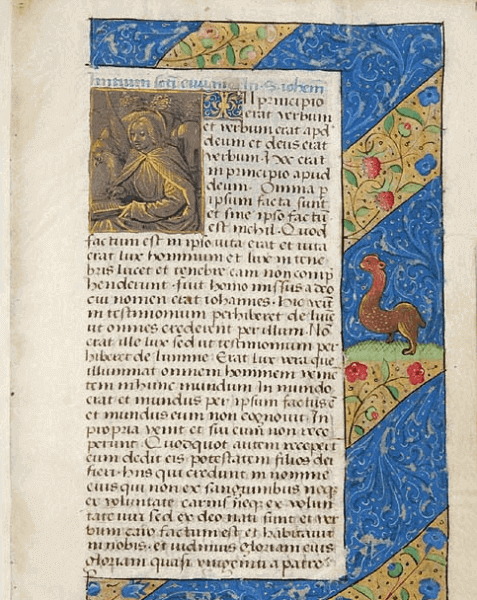

The library of the American banker Pierpoint Morgan has digitized a large collection of Medieval and Renaissance manuscripts for a project called Corsair. Illustrated manuscripts, from Bibles to books of hours, are the focus here.

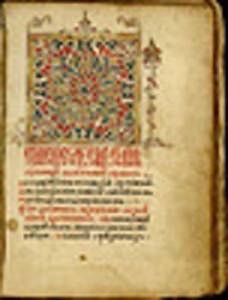

The Timbuktu Manuscripts Collection

The city that became a byword for “the middle of nowhere” was once a thriving city at the end of the caravan route in the African country of Mali. It was also a center of Islamic learning. (Including much scientific and medical education.) To this day, families in that city retain sometimes thousands of documents. But many of these are falling apart without restoration and conservation facilities. So they’re being digitized by Aluka, a project to create an African digital library.

Unfortunately, access to these images are restricted to academic types! This is a terrible idea. How would access to these digitized documents by Joe Blow or Josefina Al-Blow harm them? It’s an old-fashioned, proprietary attitude that the mere presence of digitization doesn’t eliminate. And although there may be others, it is the only attempt to digitize Sub-Saharan African documents that I know of. Anyone and everyone has access to hundreds of thousands of medieval manuscripts from France and Italy and Switzerland, but no one outside of academe has access to African manuscripts? Preposterous.

If you’ve got a favorite online repository of digital manuscripts, please chime in below in the comments.

Manuscript photo by Paul K