At this week’s VMworld conference in Las Vegas, attendees are gearing up for a series of events and breakthrough announcements beginning Tuesday, some of which are expected to come directly from the mouth of VMware CEO Paul Maritz. This while the big news already hitting the floor is Citrix’s move to full and free open source for its recently acquired Cloud.com infrastructure management system.

Somewhere in the middle of all this is Microsoft, which is not accustomed to playing the role of also-ran. Yesterday that company announced a revised licensing model, moving back to a per-processor scheme with unlimited virtual machine instances. It’s part of the company’s effort to attack VMware by going after its “V” word – de-emphasizing virtualization.

“Let’s be clear: Virtualization is not cloud computing. It is a step on the journey, but it is not the destination.” This from Microsoft’s Brad Anderson, Corporate VP and head of what’s currently being called the Management and Security Division. Under the new corporate setup, Anderson is now the company’s chief cloud spokesperson.

“We are entering a post-virtualization era that builds on the investments our customers have been making and are continuing to make,” Anderson continues. “This new era of cloud computing brings new benefits – like the agility to quickly deploy solutions without having to worry about hardware, economics of scale that drive down total cost of ownership, and the ability to focus on applications that drive business value – instead of the underlying technology.”

It will be difficult to make the case, technologically speaking, that cloud computing is moving beyond virtualization – that’s a bit like saying the automotive industry is moving beyond the drivetrain. As Microsoft’s own literature on cloud computing (PDF available here) states, “The primary vehicle for cloud infrastructure is virtualization; more specifically, running virtual servers in large data centers, thereby removing the need to buy and maintain expensive hardware, and taking advantages of economies of scale by sharing Infrastructure resources.”

But weighing in Microsoft’s favor is a publication from arguably the company’s key cloud customer, the U.S. Government. In spelling out for itself and prospective vendors just what constitutes “the cloud” and what does not, the National Institute for Standards and Technology specified classes of services, not technical foundations. NIST essentially said (PDF available here) a cloud was a self-service platform enabling rapid access to pooled resources, not a data center running a virtualized infrastructure.

So the shift Anderson is referring to is more of a change of focus, away from the center of gravity that VMware now commands and toward service and management tools where Microsoft is more competitive. In an effort to help customers change their focus along with Microsoft, the company announced yesterday a shift in the licensing strategy for its cloud infrastructure platform, moving back to a per-processor model.

Three years ago, the move away from per-processor licensing seemed to require more than a crowbar. Microsoft’s scheme for Windows Server at that time was to disallow any transfer of the operating system image away from the processor to which it was “rooted” – essentially forbidding the whole process of VM migration, which is completely necessary for the cloud principle to work.

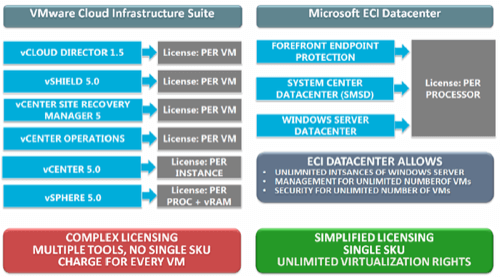

The new scheme is with respect to customers building private clouds – elastic computing realms that are built and managed by an organization, and housed on- or off-site. Microsoft’s new Enrollment for Core Infrastructure (ECI) plays off the notion that VMware uses per-processor licensing for its core infrastructure tools but per-VM licensing for its services.

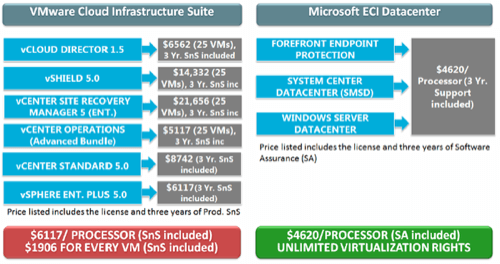

ECI, by comparison, enables unlimited (or “unlimnited,” as the case may be) VMs of Windows Server, so the new scheme avoids re-introducing prohibition. What’s more, as a marketing brochure released yesterday (PDF available here) explains, as businesses deploy more virtual machines, they could be saving about 75% on licensing expenses when the total figure enters the five-digit range.

“VMware’s current licensing for private clouds places restrictions on customers and essentially taxes them as they grow,” the brochure reads. “While the initial costs may seem tolerable for many IT budgets the long term impact as technology evolves means that costs will rise significantly, and negate a customer’s ability to benefit from the economics of cloud computing. With Microsoft, you gain the advantages of cloud economics, based on our unlimited virtualization rights.”