The long rumored Microsoft reorganization is finally here, and it does pretty much what you’d expect. It regroups the company’s scattered divisions into four main product areas, centralizes functions such as finance and marketing and runs up a “One Microsoft” banner designed to rally the company’s troops around its new “services and devices” mission.

All of which sounds straightforward enough. Will it actually make Microsoft a leaner, meaner competitor in an industry dominated by the likes of Google and Apple? That’s the big gamble Steve Ballmer is making here. Unfortunately, the odds aren’t really in his favor.

Microsoft-watchers are busily dissecting the details of who’s in and who’s out, and you can bet that lots of folks in Redmond are playing along. That’s the first problem with moving around boxes on the organization chart—the resulting job-shuffling, power-playing and general chaos usually take a long time to shake out. The energy dissipated as people figure out where they fit and how to get work done inside a new structure generally overwhelms any momentum from the big announcement.

Right Answer, Wrong Question

A bigger question is whether this reorganization even addresses the right problems. There are a couple of small reasons, and at least one big one, to think it doesn’t.

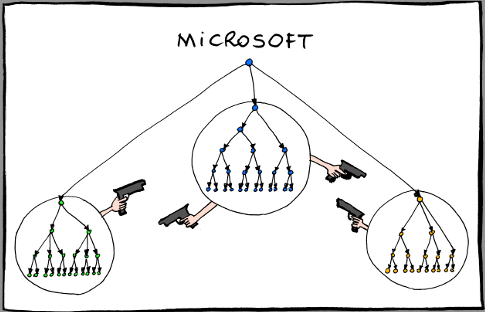

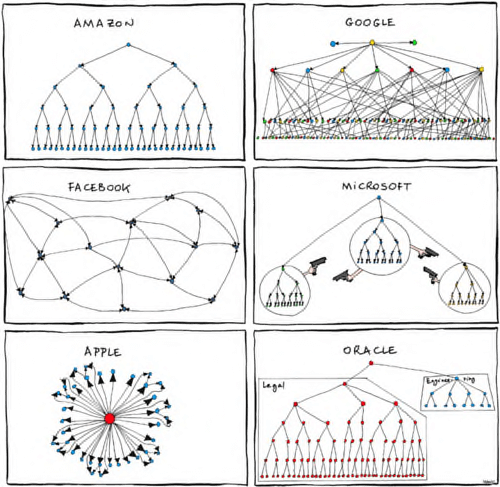

First, Microsoft’s fundamental problem over the past few years has been its inability to capitalize on new opportunities. It failed to push its way into tablet computing, smartphones and the cloud, largely because it was its own worst enemy. Microsoft’s ridiculous internal rivalries often handicapped new initiatives that might have threatened the company’s Windows and Office cash cows, a situation aptly parodied by Manu Cornet in the cartoon to the right (click for a larger version).

Ballmer’s answer is the “devices and services” orientation. He’s has been talking up this shift for roughly a year as part of his effort to shift the company’s mentality from its Windows-Office orientation. Going forward, Microsoft will concentrate its efforts on four main areas:

- Operating systems, including Windows, Windows Phone, the Xbox operating system and enterprise software

- Devices and studios, which combines the Surface and other Microsoft hardware with the company’s entertainment efforts in music, games and video

- Applications and services, the new home of Office, the Bing search engine, and Skype

- Cloud and enterprise, consisting of the Azure cloud platform and back-end data centers for other Microsoft services

It’s a classic structure that would do any MBA proud. Trouble is, it doesn’t exactly leave a lot of breathing room for innovation, which tends to flourish when insulated from incumbent products. It’s not remotely clear, for instance, that Microsoft will be any better positioned to seize new software opportunities with the Office division lashed to Bing and Skype, for instance. (Though who knows? You may soon be able to make Internet phone calls from a Word document!)

Similarly, the new OS group might well promote efficiency by unifying the code bases of various Windows flavors and the Xbox OS. But it’s equally difficult to imagine big breakthroughs in, say, cloud-computing architecture emerging from a behemoth like this one.

Of course, Ballmer can always make exceptions to this structure—and in fact he already has. Microsoft’s Dynamics CRM group, for instance, floats outside those four main product areas, connected by “dotted lines” to the applications group, marketing and sales. Where one exception exists, others can follow. Of course, more exceptions would make a hash of the consolidation effort, but them’s the risks you take when you venture into Boxland.

Treatings Symptoms, Not The Disease

There are other reasons for skepticism. For instance, Ballmer clearly aims to limit the company’s internal rivalries by taking away independent finance and marketing teams from the product groups and consolidating them at the corporate level. But that’s treating symptoms, not the disease. Product groups can and will battle for those resources wherever they are; it’s even possible that the infighting—and resulting corporate sluggishness—could get worse, not better, as groups scramble for the biggest slice of the pie they can get.

There are also rumors that Microsoft will adopt a new financial reporting structure that reveals less information about the performance of its various divisions. That may sound arcane, but it could have bad consequences. Sure, no one likes Wall Street’s short-term mentality, but the flow of financial information provides important signals to both insiders and outsiders about how well particular businesses are performing and whether new initiatives are really taking root. It’s an important corrective to Microsoft’s current mindset of mediocrity.

The new structure also clearly concentrates power with the CEO. That can be a great thing in the right hands—i.e., those of a CEO who can balance the need to keep the wheels turning while also being ready to cannibalize existing business in order to jump on a major new technology trend. Plenty of folks doubt that Ballmer is that guy. And if he’s not, his corner office could well become the next big bottleneck to innovation at Microsoft.

Just What Is Microsoft’s Raison D’Etre, Anyway?

A lot of this boils down to one big question: Does Microsoft really have a good reason for existing as a single company anymore? Doing business as a software (and now hardware) behemoth certainly looks impressive to corporate executives, board members and business partners, but you can make a pretty powerful argument that Microsoft in its current form simply isn’t capable of evolving to address the fast-changing markets in which it plays.

I was a skeptic when former Microsoft exec Joachim Kempin suggested here at ReadWrite that Microsoft should break itself up into several Baby ‘Softs. But his argument makes more sense the longer I look at the new org chart. Here’s a key passage:

But how else can you re-infuse entrepreneurial spirit in a company with a feeble or handcuffed leadership team, which mainly protects its own turf and ignores broader opportunities? To propel Microsoft out of its current predicament, I see no other way than to split the company into more manageable pieces.

Question for the class: Does anyone see anything in this particular organization that seems likely to promote innovation and the ability to capitalize on new and potentially disruptive innovations? Go ahead, have another look. (And report back your findings in comments, should you have any.)

Organization-chart cartoon courtesy of Manu Cornet. Lead image cropped from the full cartoon