Twenty-one years ago, Microsoft debuted the first Surface tablet, complete with handwriting recognition and gestures. It wasn’t called the Surface then. In fact, the prototype tablet that a young, charming Bill Gates showed off was an unnamed prototype from NCR running Windows 3.1.

In a video lost among the millions on YouTube, Gates marked the debut of Windows for Pen Computing, the first tablet interface for Windows.

Next week, Microsoft will debut its Surface, a tablet that the company introduced in June. Surface will come in two flavors, one based on the full-fledged Windows 8 operating system, and one running a derivative for ARM processors, called Windows RT, which will be priced at $499 and up.

Beneath The Surface

Those tablets flip Microsoft’s design process on its head: The Surface and its rivals guided the development of Microsoft’s new operating system, rather than the other way around. Two decades ago, the PC was at the center of the technology solar system, although even then it was clear that Gates and Microsoft were thinking about vertical industries like health care and shipping.

The original video, a production by Microsoft titled “Personal Computing: The Second Decade Begins,” opens with Gates strolling through another relic of the era, a computer store. Printers line the walls, and Gates holds up a clunky laptop that weighs “only” seven pounds.

Soon enough, however, we see why Gates is there – to promote the “graphical environment” of Windows 3. (Support engineer Joe Long notes, incidentally, that the number of support calls for Windows 3 is about 2,500, and Microsoft doubled its support staff to compensate.)

In the video’s second chapter, however, Gates introduces something new.

Pen Computing A Precursor To Touchscreens

“One of the products we’re testing today is called Pen Computing for Windows,” Gates says in the video, adding his own spin to the brand name. “The idea is that hardware manufacturers will be building PCs that include a touch-sensitive surface.”

“You use a pen, right here on the surface, and you can handwrite, just like you can on paper, and the computer recognizes it,” Gates adds. “So you don’t have to use a keyboard. So a machine like this could be taken into a meeting, or out on a sales call, and used in a very natural way. We’re making sure that it’s easy for people to work with Windows for Pen Computing.”

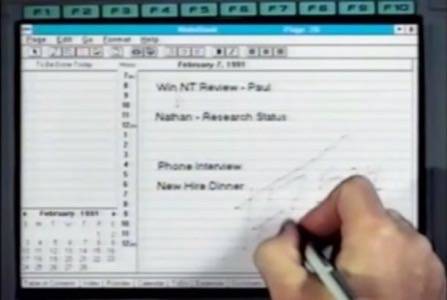

Byron Bishop, then a lowly product engineer (later ascending to become the executive vice president of Expedia, and beyond) shows off the tablet interface by first clicking a calendar tab, then a date, then pulls up a schedule. The Pen Computing interface allows Bishop to draw an amusing little map of the location (no calendar-to-map integration, then!) which is saved as digital ink, automatically. Bishop also then scrawls in a new appointment, which is automatically converted into text and saved.

At this point, handwriting recognition wasn’t new; both Pencept and CIC offered PCs with handwriting recognition built in, according to Wikipedia, and 1989’s GRidPad went on to inspire the Palm Pilot.

Still, simply being able to scrawl a note and have it translated into actual text looks pretty impressive, even today. Vision Objects, for example, recently signed a deal to power the Samsung Galaxy Note and Note 2 with its handwriting-recognition system, and company executives demonstrated the same sort of handwriting-to-text capabilities that the Windows for Pen Computing demonstration included.

The tablet also translates drawn lines and circles into their digital equivalents. There were even gestures: “If you want to delete something, you just swipe through it,” Gates says. “That’s one of the easy-to-remember gestures.”

Gestures like cut, copy, paste and other common functions used their own shortcuts, while user-defined functions (macros, basically), were letters in a circle. People could also train the system to recognize quirks in their handwriting, such as connecting the horizontal swipe of a “t” with the lower hump of an “h.” Gates also showed off the ability to sign a form and connect to a database, both useful functions for a mobile tablet used for shipping and receiving, for example.

Unfortunately, certain elements of the Windows for Pen Computing interface were found to infringe upon patents held by GO Corp., a rival and pioneer in tablet computing. In 2005, Go filed suit against Microsoft; technology developed by GO eventually found its way to Alcatel-Lucent, which successfully sued Microsoft for $512 million for patent violations.

Still, the video is impressive, not just for the history, but as a reminder that Windows 3 was actually useful. If you buy a new Surface, remember, some of its capabilities Microsoft has touted are more than two decades old.