Sadly, it’s going to take a long, long time before we can shrink people and submarines small enough to be injected into an ill patient, a laFantastic Voyage. But it turns out that shrinking the people isn’t necessary to realize the idea.

Easy-To-Swallow Diagnostics

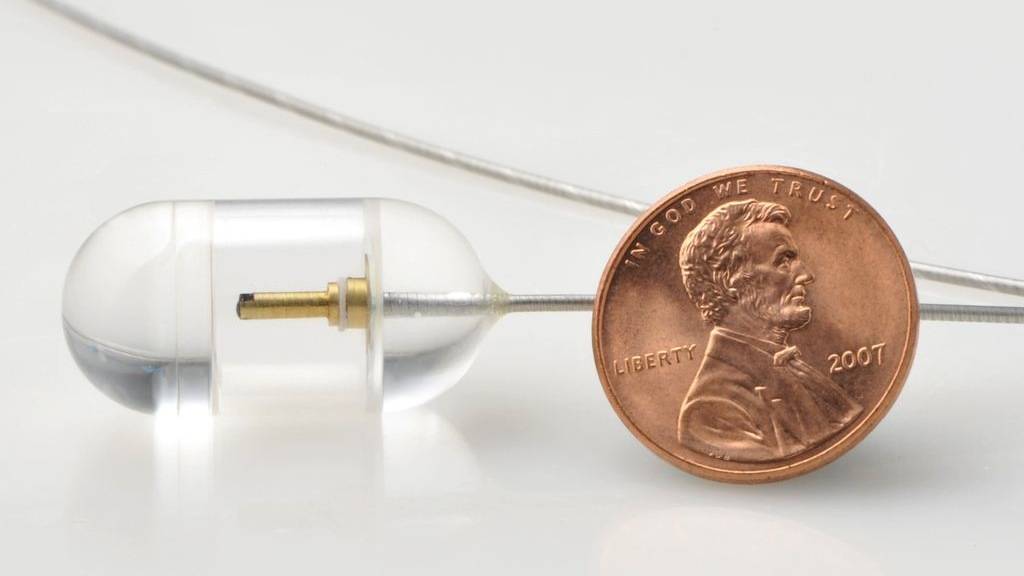

A team of doctors and researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital have created a pill-sized, tethered lab that patients swallow, and they are preparing to commercialize it. The 1-inch glass bead, in the shape of a typical multivitamin, can take better-than-high-def video and stills (what, no audio?) of a person’s entire esophagus, that tubular organ that starts at the back of your mouth and ends at the entry to your stomach.

This is big news for anyone who has problems with their esophagus, notably the one-in-five Americans who suffer from acid reflux disease – which can lead to lesions known as Barrett’s Esophagus, which can lead to highly fatal stomach cancer.

The Old Way Hurts

Today, such patients periodically undergo an upper endoscopy, a $1,500 procedure in which they are anesthetized so that a specially trained physician can slide a long, flexible, black video camera and remote tool kit down their throat. Ouch!

Over the course of about 40 minutes, the team watches a video screen for signs of trouble – seeing only what’s on the surface of the surrounding esophagus. Along the way, the doctor can use tools near the lens to snip off bits of flesh for later examination.

No Knockout Juice Needed

About 18 months ago, the team, led by Dr. Gary Tearney, at Massachusetts General’s Wellman Center for Photomedicine, was kicking around ideas for simplifying the procedure. This is what they came up with:

You pour a cup of water in your mouth, put the device (attached to the end of a tether) in your mouth and swallow the water and probe at, say 2pm (this is important). No knockout juice.

The thin tether, containing a fiber-optic cable, dangles from your mouth as a doctor – or even a technician – lightly holds on. The same rhythmic muscle contractions that deliver swallowed coffee to your stomach even if you stand on your head does all the work, pushing the bead along.

“We were skeptical,” said Tearney. “We thought the bead would be loose in the esophagus.” Picture a small elevator in a big shaft. For it to work, the device had to be in contact with tissue. “I was shocked and amazed that the esophagus clamped down on the probe, giving us full contact all the way around. “I had no idea it would work this well.”

A Better Picture

The fiber optic cable shoots near-infrared light onto a tiny, rapidly spinning prism that reflects it out a microscope lens. The focused light scatters inside the tissue and, using sonar-like principles, software written by Tearney’s team builds a picture of features within the lining based on how long it takes the light to rebound. The information hits the prism and races back up the same cable to be reconstructed as a real-time, deep-tissue image, showing healthy and damaged flesh in minute detail.

The technician can pull the probe back at any point, but after shooting the whole esophagus, that little glass bead likely will exit your mouth at 2:06pm. Six minutes after the start of the procedure.

The probe has been tested on 13 patients so far, and has returned detailed images quickly, less expensively and without sedation. If doctors spot dodgy cells, they schedule a traditional upper endoscopy, with the snaking camera, anesthesia and snipping tools.

Still In Testing

Tearney declined to predict how much the tool, which requires purpose-built electronics, would cost. He did say the new procedure could be done in a doctor’s office, not in a much more expensive hospital room.