Facebook’s Native Mobile Problem With Open Graph

In 2010, Facebook attempted to redefine the meaning of “verbs” in the Web Era. The company’s Open Graph turned users actions (such “Jon ran” or “Susie listened”) into status updates, tied to Web apps. The Open Graph opened up a new world of data to Facebook and its developer community. But there was a hitch and, like many of Facebook’s recent issues, the source was mobile. In the Mobile Era, Facebook’s Web-centric approach has caused it many problems, from monetization to user experience in its mobile app on iOS and Android.

On the other hand, Facebook’s biggest strength is its ability to make connections between its users’ friends, what they “like” and what they do. The more threads that Facebook can tie to a user, the better able it is to sell advertising to them. That makes Open Graph the biggest single innovation Facebook has introduced in the last few years.

Integrating Open Graph has been a problem since the it was announced in 2010 and expanded in late 2011 to include the new Timeline profile. Apps with Web-based back ends, such as Spotify, have been easily able to use Open Graph but the option for most native developers was beyond their means. But developers with “native” mobile apps had to go through extraordinary lengths to tie the Open Graph to their applications and only a handful of well-funded startups (such as Instagram or RunKeeper) with big development teams have been able to pull it off. The problem was that the backend systems for native mobile apps are difficult to optimize to Open Graph.

Kinvey’s Middle Point

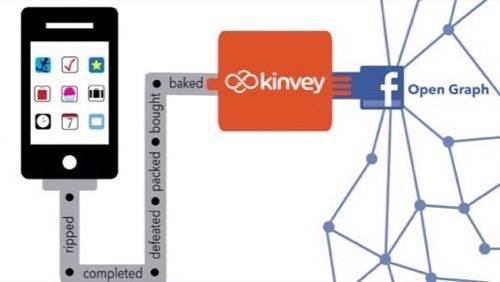

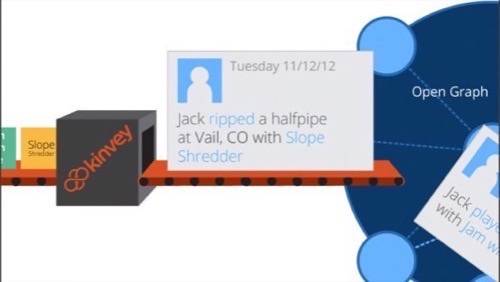

A startup in Boston is aiming to fix that. Kinvey, a “Backend-as-a-Service” provider for mobile application development, has created a simple way for native developers to connect their apps to Open Graph and allow users to use easily use more “verbs” on their timelines from their smartphones and tablets.

Open Graph functions by pulling in data from Web endpoints by connecting the action (verbs like “run,” “cook,” “listen” etc.) with metadata from the Web app. So, if I am baking cookies, I can hit the “I baked cookies” button on some webpage and Facebook will crawl for the metadata associated with that action and post it to Timeline. This works only because the webpage has metadata, stored on the Web, that Facebook can crawl. Mobile apps do not often have this type of metadata available to be searched, nor any backend system or URL that Facebook can crawl.

Kinvey has a simple solution. It takes the metadata (known as the “object”) from a mobile app and hosts it on its own servers. It then takes that data and creates its own Web endpoints for Facebook to crawl. It is a clever bit of integration. Kinvey is not changing the basic nature of Open Graph nor doing anything extraordinarily technical, rather it is creating a new middle point between a developers’ apps and the Open Graph – with an interface that lets them push or retrieve data. Kinvey sets up the entire system on its own and handles the data flow for the developers.

Good For Everyone?

The benefit for mobile developers is clear: they can extend native apps actions to Facebook’s entire population and make them accessible on Timeline without creating an entirely new structure.

Facebook benefits because it does not have to completely reconfigure Open Graph to serve the large native mobile developer environment. Plus, it gets previously unavailable data from smartphone and tablet users. This could significantly help Facebook spread through the app ecosytem just as it has already done with Web pages.

Users get the benefits of Open Graph on the Web extended to mobile applications.