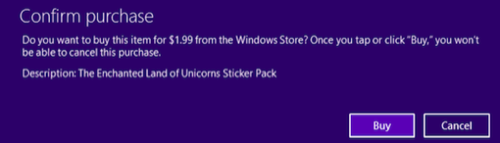

On Friday, Microsoft revealed that the minimum price for a paid Windows 8 app would be $1.49 – 50% more than the 99-cent entry-level pricing that most mobile users have been accustomed to. Has Microsoft priced itself out of its own app market?

Possibly. But based on its history with Windows Phone, increased revenue for app developers may be exactly what Microsoft needs.

Microsoft revealed the new pricing for the Windows 8 Store in a blog post authored by Microsoft’s Arik Cohen, lead program manager for the commerce and licensing team. The pricing tiers will range from $1.49 to $999.99, incremented in 50-cent steps. Developers may also “sell” their apps for free, either giving them away, using a time-limited trial, or subsidizing them via in-app ads or upgrades.

The tiers are necessary, Microsoft has said, to ensure that an equivalent price is selected for selling the app in any currency supported by the store. Microsoft itself keeps 30% of the revenue, dropping to 20% after total app revenues reach $25,000.

Metro Apps Only

For now, “apps” within the Windows 7 version of the Microsoft Store are essentially digital versions of boxed PC software, with a typical price of $30 or more. But Windows 8’s Metro apps, which will share native C and C++ code with Windows Phone 8, should mean that the mobile app pricing model should bleed over into the Windows Store, dramatically lowering the average price. (Microsoft has also said that the only apps sold within the Microsoft Store will be Metro apps; “desktop” apps will be sold outside of the Store framework by the individual developer.)

So why is there no 99-cent tier? And is that significant?

The data suggests that, by and large, it probably isn’t. More importantly, studies have revealed that Microsoft mobile app developers make far less than other platforms.

Who Makes Money on Apps?

For one thing, developers have a number of different ways of making money from a mobile app, of which most, if not all, should be available to Windows 8 Metro app developers. According to a June 2012 study by Vision Mobile, 34% of the 1,473 developers polled used a per-download pricing model, pulling in an average of $2,451 per month across all mobile platforms.

But developers also have a number of other ways of making money. The most lucrative method is subscriptions, which averages $3,683 per month. However, convincing customers to sign up for recurring payments can be tough, and only 12% of developers were able to make that work. Developers also pull in more money per month ($3,033) using in-app purchases. Other choices include the so-called “freemium” model and in-app advertising, both of which generated less monthly revenue than a paid download.

Merging Mobile and PCs

More than half (54%) of the developer polled by Vision Mobile also said that “reach,” or the number of devices upon which an app can be run, determines their choice of operating system. Clearly, Microsoft is hoping the broad overlap between the millions of Windows 8 PCs and Windows Phone will help make the platform more attractive to developers.

But Microsoft developers have also had their share of problems. According to Vision Mobile, Windows Phone apps are relatively cheap to produce: $17,750 on average, with lower development costs than an iOS app ($27,463) or an Android app ($22,637).

Windows vs. iOS, Android and Blackberry

But the average revenue for a Windows Phone app is tiny: just $1,234 per month. That’s about a third of the almost $3,700 per month an iOS developer can expect, and still significantly less than the $2,735 an average Android app pulls in. (Surprisingly, BlackBerry remains by far the most profitable platform, with revenues of $3,850 per month on development costs of just $15,181.)

And in all, it takes a Windows Phone developer more than a year – 14 months – to break even, double the payback period for iOS developers. Is it any wonder, then, that Microsoft is reportedly subsidizing the development of Windows Phone apps?

The final wrinkle is consumer behavior. Based on a January report from Distimo, of the ten highest-grossing applications within the iOS App Market for iPhone, six used a pay-per-download model. But of the top ten highest-grossing Android apps, just two used a paid-download model. The rest – Android and iOS both – generated revenues from in-app sales. Consumers display different buying behaviors for each app store.

What these numbers seem to tell us is that Microsoft believes its Windows Store can be a destination for premium app buyers, much like Apple’s own app store. The company is clearly betting on the combined reach of Windows Phone and Windows 8, and hoping buyers will continue their old habits of buying software for dollars, rather than mere cents.

For more on Microsoft’s future in the apps business – especially on the enterprise side – see Dan Rowinski’s [Survey] Developer Interest in Enterprise Apps Likely to Benefit Microsoft.