“A lot of the noise in the market right now is about bringing back irresponsible IPOs. That is a short-lived strategy, and a wrong-headed strategy.” This from Kate Mitchell, the former chair of the National Venture Capital Association, and current Managing Director of Scale Venture Partners. “Our objective is to bring back quality IPOs, the kind that we had in the late ’80s and the early ’90s.”

Mitchell is responding to criticism that a bill based on her own work may undo some of the benefits of the Sarbanes-Oxley law, which tightened reporting regulations and increased transparency for businesses. But she’s making these comments while taking a victory lap. In fact, today she’s at the White House, watching President Obama sign the bill her task force put in motion.

In March 2011, the U.S. Treasury Department assembled 17 leaders of the startup business investment community, under the auspices of its Access to Capital Conference. Their task was to draft a set of recommendations for how the nation’s “IPO crisis,” as some call it, could be resolved – a post-bubble lull in the number of startup companies in all sectors that proceed to the initial public offering stage and go public. Among their recommendations was something called an “IPO on-ramp:” a five-year relaxation in the reporting requirements for companies in the formative stage. This while increasing the limit on small investments in these companies by 10 times, and legalizing crowdfunding.

In an interview with ReadWriteWeb prior to the signing ceremony, Mitchell speaks about the formation of the IPO Task Force and the process of crafting their recommendations – a bit of it in jest: “It was meant to be a diverse group, and that really gets to the point of why we got to the recommendations we did. We had institutional public IPO buyers on the task force, they got two votes. (I joke.) There were CEOs and private investors, securities attorneys, the former head of [PriceWaterhouseCooper’s] tech practice in Silicon Valley. Then we had some boutique investment banks, and I joke that they got half-a-vote.”

It was a diverse enough group of financial professionals, she tells us, that they could all come in with their preconceived notions of why the market is in the state it’s in, and then come to recognize those notions for what they were. Throughout the summer, as often as three times a week, the group would come together to hash it out over ideas that one side of the room believed was beneficial for the folks they represent, that the other side of the room couldn’t swallow. It’s the type of issue-driven discussion that used to happen inside the walls of Congress, back before politics became a sporting event.

“We really ended up coming up with something that reflected what will work for the ecosystem,” remarks Mitchell about the group’s recommendations, which were largely adopted by Congress. “It was meaningful for issuers, but provided for investor protection from the investor perspective. So that’s [the] really why we brought that diverse group together; it wasn’t just any one given group of people, or from any certain part of the ecosystem. It was a diverse group.”

The task force recommendations, titled, “Rebuilding the IPO On-ramp,” presented stunning insight into the symptoms of the nation’s startup problem. During a 25-year span of time until 2005, their final report noted, nearly all net job growth in the U.S. was created by firms less than five years old. Some 92% of job growth comes after a company goes public – which makes sense, because a company acquires public capital in order to hire people.

But in 2008, only 45% of companies went public. And in an August 2011 survey by the IPO task force of CEOs of companies in both the pre- and post-IPO stage, while every single one agreed a strong IPO market is important for the U.S. economy and for maintaining competitiveness, 86% of CEOs surveyed said that going public was a less attractive option for businesses today than in 1995.

The report suggested that one reason for this change in sentiment may lie in how Sarbanes-Oxley (SOX) and other regulations tailored toward holding large companies accountable, may be strangling smaller and newer ones. “A series of rules, regulations and other compliance issues aimed at large-cap, already-public companies has increased the time and costs required for emerging companies to take this critical first step,” the report stated. “Many of the rules and regulations adopted over the last 15 years aimed to respond to scandals or crises at major public companies and to restore confidence in the public markets by requiring public companies to adopt more stringent financial and accounting controls.”

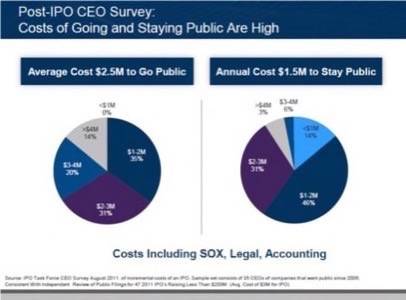

The survey learned that the average cost that companies sustain just to go public was $2.5 million, and companies spent another $1.5 million per year just to stay public. RWW asked Kate Mitchell how much of that expense was actually wrapped up in meeting reporting requirements and hiring independent auditors. She told us that SOX accounted for about 30% to 40% on average, although for one company in the survey, the cost for going public exceeded $4 million.

Mitchell tells us about her experience testifying before Congress at the time the task force was first being assembled. Also speaking during the same session was Seth Goldman, the founder of Honest Tea. “He said it’s become so daunting to go public that he would rather stay private.”

This was the genesis of the task force recommendations for relaxing SOX for small companies. But the relaxation itself comes with limits, Mitchell tells us – limits that maintain the spirit in which the reporting rules were created, and which many investors actually insisted should remain.

“One of the appeals we got from institutional investors was that they want to invest in growth companies on the public regulated exchanges,” the former NVCA head tells RWW, “They know, they trust, the ways of doing business on a regulated exchange; [whereas] what they have to do now is to go into the second markets in the private world, where buying and selling securities are governed by contractual law. And they’d rather be in a regulated environment rather than a contractual environment. So the idea that a) we would allow more IPOs, but b) it had to be consistent with SEC regulations, was really the intent of what we were doing.”

Mitchell listed for us the reporting and transparency requirements that do not go away as a result of the JOBS Act: The ban on investment banks using their own banking revenues to pay for investment research and analysis – known as the “Spitzer Decree,” after the former New York attorney-general who drove it into law – remains. The FINRA Rules of Conduct, which stipulate – among other things – that independent research analysts must have their independence certified, also remains. “All the accounting disclosure requirements in GAAP stay in place,” she added. “This is actually borrowing from existing SEC regulations that apply to small companies.” She then noted that small reporting companies (SRCs) with a public float of under $75 million, or annual revenues of under $50 million, are already permanently exempt from SOX regulation 404(b). “The CEO and CFO are still personally liable to assert that they have certified for any material weaknesses. The auditors, when they find them, have to disclose them.”

“You do know that General Motors, when they go public, gets up to two years themselves to comply with the external audit of internal controls, which is a ‘belt-and-suspenders’ approach, and a very reasonable thing ultimately for all these companies to provide. We’re simply saying, give these smaller companies slightly more leeway than the largest companies already have,” Kate Mitchell says. “We didn’t want this to be a radical recommendation; we wanted to have companies that public investors are going to want to invest in, because they have confidence in the numbers, the source of the information they’re getting outside the company, about the company… CEOs find public markets unattractive today, and we want to take that away. That’s part of the problem. That’s why they don’t grow to be big.”