A company called Sopods, makers of the Full-Screen Web Browser application for the Apple iPhone, have just implemented new ground-breaking anti-piracy measures for the iPhone platform. After pirated copies of the company’s application began to surface in the wild, the application’s developer, angry about the lost income, came up with a way to detect the cracked apps and then turn them back into “demoware.” With this process, the cracked apps will still work, but a message will appear after 10 runs encouraging the owner to purchase the legal copy in the iTunes store or exit the application

App Phones Home, Tracks Pirates, Nags Them to Buy

Ben Chatelain is the software engineer behind the Full Screen Web Browser application which was released in the iPhone App Store on February 12th, 2009. It soon became fairly popular, having now been downloaded over 66,000 times and ranking in the Top 100 Paid Apps lists in ten countries. In the U.S. and nine other countries, it also ranks in the Top 20 Utilities list.

However, within four days of the initial release, Ben received a Google Alert informing him that a cracked version of the application had been made public on Appulo.us – a site that supposedly provides the “try before you buy” functionality that’s currently missing from iTunes. In theory, users can download and evaluate applications using Appulo.us, but in reality it mostly serves as a way to download pirated copies of paid iPhone applications for free.

Upset to find his application pirated, Ben began to investigate ways to detect the cracked apps in order to do something to the pirated copies out there, like shutting them down remotely or causing them to self-destruct. Still, he didn’t want to do anything that would affect legitimate users of the app or cause problems with Apple that could lead to his app being pulled from their store.

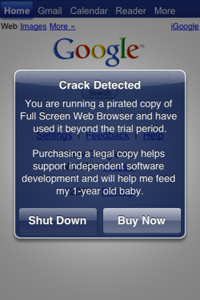

Instead, Ben developed a server callback mechanism that alerted him when a copy of his application was cracked. The data sent back to him included the app’s unique device identifier (UDID). For those applications registered as cracked, the server will now control a demo period. After 10 runs, a message is presented to those running the bootlegged copy, encouraging them to purchase the Full Screen Web Browser page in the App Store. The only other option provided is to exit the application.

In addition to the warning message, Ben also cleverly adds a “guilt trip” to the message, informing the users of the pirated copies that purchasing the application legally will help him feed his 1-year-old baby. (He decided against his wife’s suggestion of actually putting a photo of the baby in the message.)

Says Ben, one of his main motivators for choosing the server-controlled demo option was because with iPhone applications, there’s no way to save data outside the tightly-controlled sandbox in which they run. That means that demo periods could easily be reset by simply reinstalling the application. His method, which uses a web service instead, lets him control applications from outside the app’s sandbox.

Piracy Troubles

Since the announcement of Crackulous, a program for pirating applications from the iPhone App Store, a lot of developers have been discussing what they can do to prevent their applications from becoming compromised. Some game developers have considered using server-based tracking methods to separate the high scores of the pirates from those of the paid users, but to our knowledge, no one has yet implemented anything like this yet.

Other developers are turning to solutions like Kali’s Anti-Piracy service, which is installed as an additional layer of protection on top of the application itself. Although not entirely foolproof, it does make it more difficult for hackers to crack an application. Hackers attempting to crack Kali-protected apps will end up with non-functional copies, says the company.

But unlike other anti-piracy methods, Ben’s server-controlled method, inspired by John Gruber’s article on Daring Fireball, allows for the possibility of converting pirated copies into paid versions. Since the introduction of his new anti-piracy measures only two days ago, 23 of the pirated users have seen the “crack detected” message. One of the 23 ended up purchasing a legal copy. Ben reports that the current rate of pirated users is around 9.1% (758 pirates out of 8241 users who have run the app since the crack appeared). For applications whose install base is even larger, turning pirates into customers in this manner could have even a greater impact. This method could be especially useful to iPhone game developers, who, according to a game developer quoted by Gruber, are the most affected by piracy. For example, two out of three users of that particular game ran bootleg copies of the application.

The server-based tracking method implemented in the Full Screen Web Browser represents what is likely to be only one of many future attempts by iPhone developers to prevent their apps from being cracked and pirated. Expect to see more of the same soon.