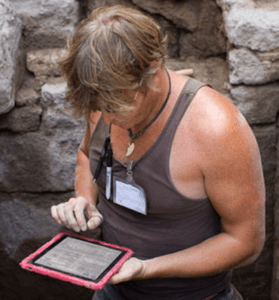

Given the successful experiments with new technology over the last few years, I believe archaeology’s alleged resistance to new technology is changing. As if to underscore that change, Apple has equipped a team of excavators at Pompeii with the iPad.

But is handing out a half dozen tablet computers to archaeologists really “revolutionizing how scientists work in the field”? Or is Apple overselling what their products can do for us in our search for a greater understanding of our own voyage? Is it perhaps more true to say that the iPad, a 21st century tabulae ceratae, is extending and amplifying what remains essentially the same undertaking that occupied Giuseppe Fiorelli 150 years ago?

An iPad in Every Trench

Apple provided six iPads to the University of Cincinnati’s Dr. Steven Ellis, who directs the UC’s excavations at the ancient Roman city. Pompeii, along with Herculaneum, was preserved in ash after the eruption of Vesuvius, the volcano near present-day Naples, in 79 A.D. Ellis’s team is focusing on establishing the detailed shape of an unexcavated neighborhood off of Pompeii’s main road.

Update: John Wallrodt, Senior Research Associate in the Department of Classics at the University of Cincinnati and a colleague of Ellis, clarified the manner in which they developed the processes they are now using at Pompeii.

“I had almost all of the tech and procedures in place in 2009 on the iPhone OS. We even tested the database entry on one of the trenches but the conclusion was that the device was just too small. So we were rather excited that there was a larger device announced in the winter. That is how we were able to purchase them in the spring and have a quick training turnaround to implement their use in the summer.”

Those unfamiliar with archaeology may presume that the bulk of the work is done with cameras and other devices. But given the conditions – dirty or dusty, rainy or bone-dry – and the requirements of the information, it is more often done with pencil or pen and paper. Photographs need to be lit right and even then certain aspects of the image cannot easily be emphasized. A good dig artist, however, can capture the smallest ding or scratch, a ding or scratch which may be the key to understanding the site. Portable computers, by and large, do not tolerate the conditions very well, can be bulky and heavy and come with heavy power requirements.

Apple asserts that the relatively long life and light weight of the iPad make it usable where a laptop would not be. That may be, though it is still a fragile device, relatively. Access to connectivity and even electricity in digs that are not next door to a large, modern Italian city, may also limit its usefulness. Ellis mentioned in his initial write-up of the experience that as easy to use as the iPads are advertised as being there was, nonetheless, a “steep learning curve” for the supervisors assigned the devices.

Paperwork vs. Spadework

Excavations, because they are dependent on exacting records, are as much about filing paperwork as it is uncovering ancient pottery and architecture. Among the types of paperwork a dig generates are forms to fill in describing object location, notes, drawings and Harris Matrices (stratigraphic diagrams). All of this material would need to be written or drawn, usually on paper, in situ. When the archaeologists got back to camp, they would need to transfer that information into a database.

Ellis, however, has outfitted his team’s iPads with FMTouch, Pages, iDraw and OmniGraffle. By using these apps, dig personnel drop information straight into the database from the field. The time that is saved by doing so is estimable.

Like Ellis,Chris Fisher, used handheld technology for his initial survey of the ancient Mexican city of X. Instead of the entire season, it took him a week to map the city, and in the process he discovered that his site was a lynchpin to understanding Western Mexico at the time of Aztec domination. The realization of what he was capable of led him to change his excavation plans to an in-depth real-time map of the whole area instead of a series of spot digs.

If there is a revolution here, I think it is a revolution of time. It may be less dramatic than the qualitative revolution Apple’s marketing may lead you to believe is being staged, but this quantitative revolution in field sciences may contribute to a kind of archeological singularity. Who knows what we’ll discover about ourselves now that we have time on our hands?

Update: Dr. Ellis responded to our post. The response was long, so this is an edited version. I’ve posted the full response in comments.

“(Revolution) is a word I chose carefully, and it comes from an academic who is actually using these things, not a marketing person trying to sell them.Quite apart from the time saved – which, I must add from the perspective of a dig director, is immeasurably valuable in terms of economic and human resources – the ability to record so many more things, and so much better and more clearly, and to then have access to that and other datasets is why I used the term ‘revolution’. Find any archaeologist who has actually USED an iPad on a site (not just thought about it), and they will doubtless agree.”

Perhaps. I still think the word “revolution” may more evocative than accurate. I don’t doubt that it has made Dr. Ellis’s work easier to do more of. But there still doesn’t seem to be a qualitative difference in the way the work is done. It doesn’t take an archaeologist to see a disconnect, just someone sensitive to language and to the way companies with products to sell leverage such statements (even if, as in this case, they did not apparently originate the term.)

What do you think? Is there a point where the improvement of an already existing process becomes a kind of revolution in fact? Does “quantity has a quality all of its own”?

Excavation photos from Apple | wax tablet photo by girlinblack