Yesterday we wrote about the positive and negative consequences of living a hyperconnected life. One becomes more accustomed to multitasking, shuffling through personal and work-related tasks, and a heightened ability to pick out nuggets of information that are actually useful. On the downside, one can become obsessed with the Internet, and find themselves feeling sad and lost when they do leave the glowing screen(s). As we become more accustomed to being kings and queens of our own Internet worlds, our brains do quietly adapt to new stresses and modes of cognition.

But what of identity? How do we define who we are online vs. who we are offline? In our hyperconnected world, identities are fractured. Facebook wants to be your online identity’s one true login. Studies have shown that we perhaps divulge more online than we otherwise would offline. Social networks are strange indeed.

Will we be happier, healthier people if we follow Zuck’s advice and become one with the Internet (and give all our data to Facebook)? Or should we stick to a more 4chan-esque approach, which suggests that we’re way more complex than that?

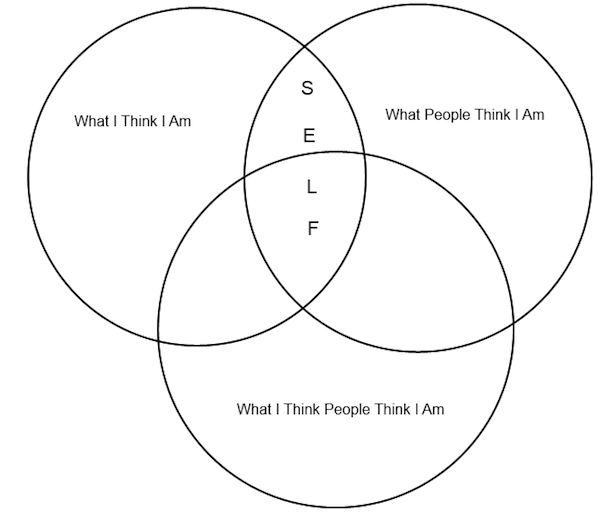

In our real lives, we constantly struggle between who we think we are, what others think we are and what people think we think we are. The real self is saddled somewhere in the overlap between these three circles. These ideas of the self apply in both an online and offline context. This abstraction, explains ScepticGeek, may come at least partially from Carl Rogers.

Online, we battle with the same conflicts, plus a few other quirks. We are a Facebook identity (or two), a Twitter account, a LinkedIn oh-so-professional account and maybe even Google+ (plus search your world, no less). Each online identity is in and of itself an identity. Maintaining them is hard, often times treacherous work. We must slog through the Internet-addled identity quagmire.

“It’s not ‘who you share with,’ it’s ‘who you share as,'” Poole says. ReadWriteWeb’s Jon Mitchell continues that thought: “In other words, we’re only presenting one, Facebook-facing aspect of ourselves when we share online via Facebook,” he writes in his story, A Proposal to Fix Online Identity. “The advertisers who make Facebook possible don’t have a full picture; they have a Facebook caricature.”

Keeping that in mind, your online persona will always be just that – a persona, a caricature of the real you. But how much should that differ from the real life you?

It all comes down to trust: Are you who you say you are? Can others trust you?

In ScepticGeek’s post, he suggests that you’ll experience quite a bit of stress if you are different online from how you are in real life. It’s not easy being two different people. But one writer argues that online it is indeed easier to make oneself vulnerable, which is part of the appeal of social networks.

“When people have the opportunity to separate their actions from their real world and identity, they feel less vulnerable about opening up. Whatever they say or do can’t be directly linked to the rest of their lives,” writes Rider University’s John Suler. He coined the term “disinhibition effect,” which suggests that people on social networking sites feel free to share very personal things that they might not share in real life. But online actions do have real, offline emotional consequences.

So consider how much of your online persona does match the offline you – not in terms of ads you look at and click or products you buy, but how you behave.

“A Marsh Frog” image courtesy of Shutterstock. Complex identity chart via ScepticGeek.