On March 9, Gigaom abruptly laid off its entire staff, including me. It’s heartbreaking to lose a job like that, but support networks have a way of making you feel certain new opportunities are on the way.

What’s not certain is the past. During my two years at Gigaom, I wrote close to 1,000 articles. My senior colleagues have five times more in their archives. We have no idea if or when Gigaom.com will be taken down. It’s as if years of our lives could disappear in an instant.

There are support networks for this kind of situation as well. The Internet Archive, for example, has been grabbing Gigaom’s web pages as fast as it can, according to archivist and software curator Jason Scott. I had the chance to sit in on Scott’s SXSW panel and felt the worry lift from my shoulders just the slightest bit.

Remembering The Internet—All Of It

Most of us know the Internet Archive from the Wayback Machine, which allows you to drop in and browse a website at any point in its history. Here’s Gigaom founder Om Malik bragging about Business 2.0 beating Wired in a game of softball in 2004:

Internet Archive doesn’t just do web pages. It preserves software, books, movies and anything else that could someday disappear or change form. As of January, you can play classic games like Oregon Trail in-browser. You can easily spend hours basking in the nostalgia.

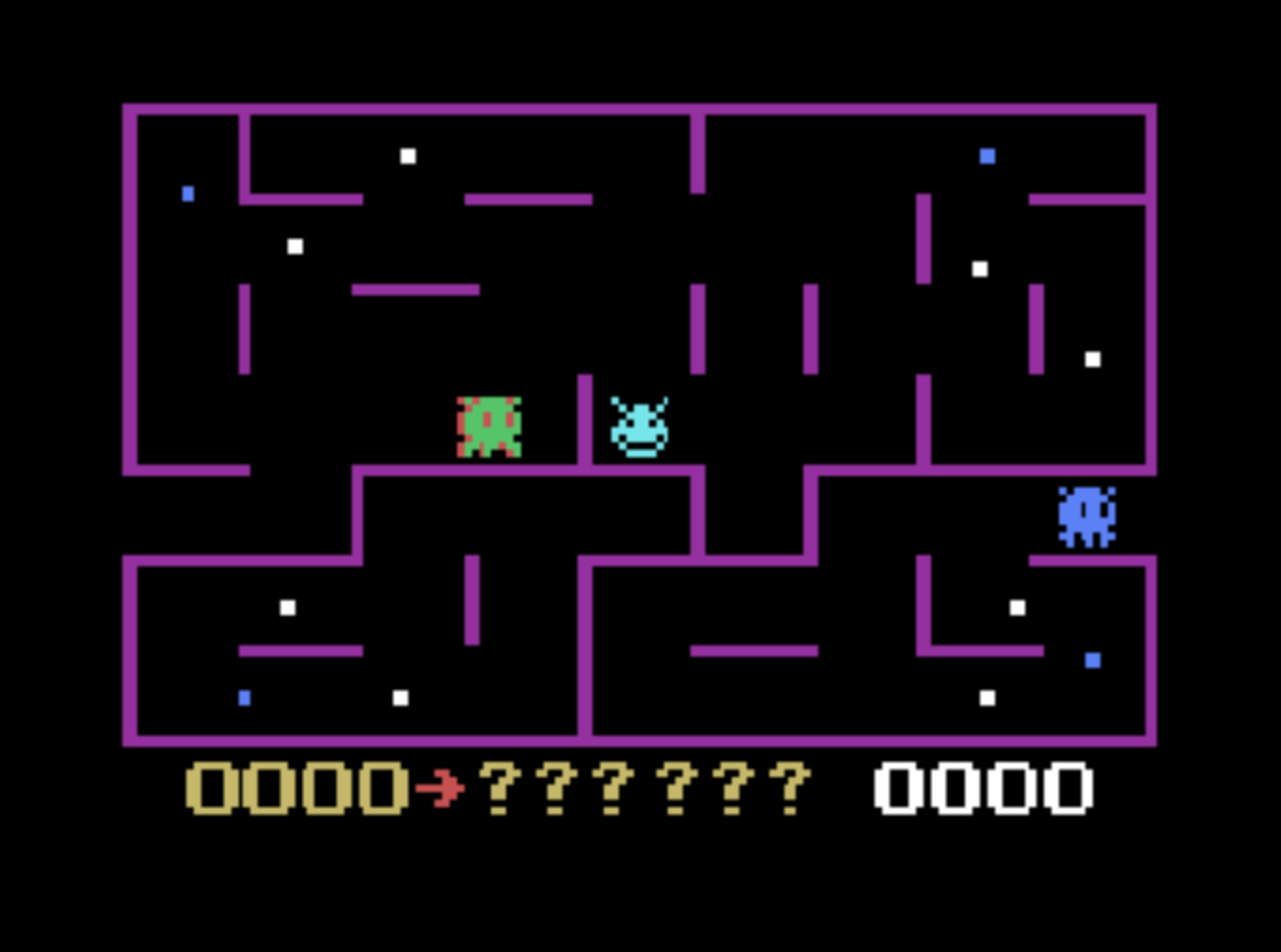

A lot of these games are incredibly rare. There’s ET the Extra-Terrestrial, a game that sold so poorly that Atari buried most of the copies in a landfill until they were recovered last year. And then there is Munchkin, which was banned after Atari sued its creator Philips over its likeness to Pac-Man.

The games’ addition created a huge splash in the media. It was the first time most people had access for decades, unless they still had a copy and the hardware to run it, or the knowledge to find a ROM through a service like BitTorrent.

History Should Be Boring, In A Good Way

“What I really want is for it to be boring as hell,” Scott said, meaning that historical materials should be so at our fingertips that it no longer feels novel to access them. (While on stage, he casually began browsing the web in browser pioneer Netscape.)

That means emulating the experience of playing a game or visiting a webpage (the pixel should feel and react the same), but also providing documentation so future generations know why the heck a game that kind of does look a lot like Pac-Man is so important. It’s just a big online museum that preserves some of humanities’ greatest works the same way the Louvre takes care of the Mona Lisa.

Scott acknowledged Internet Archive’s coverage areas can be spotty. Part of that is the legal gray area that can come with posting commercial works. Internet Archive usually complies with takedown requests if a product is still being sold. A possible solution is posting works behind a paywall, so their creator can still get their due. But once it becomes public domain, it is already preserved in its original form.

Save Everything

Scott urged audience members to preserve as much of their personal work history as possible. That means putting brainstorming napkins, every version of a software program and colleague’s business cards in a shoebox and taking it back out 10, 20, 40 years in the future. We can’t rely on one web site or company to take care of its own preservation.

“The vast majority of human photos are up on Facebook and nowhere else, and that’s a dangerous thing,” Scott said. “I of course believe grab everything.”

After that, he said, entropy and time can choose which digital works we choose to remember.

This past week has made me optimistic that the world will choose to remember Gigaom. But even if it doesn’t, I feel safer knowing that when I’m 80 I can hop into the Wayback Machine and relive a few of those 1,000 articles.

Lead photo by DRs Kulturarvsprojekt; screenshots courtesy of the Internet Archive