“Images were first made to conjure up the appearance of something that was absent,” writes John Berger in his seminal publication Ways of Seeing. “Gradually it became evident that an image could outlast what it represented.”

On the Internet, where variations on the Hey Girl meme live and die, Nicki Minaj battles it out against Katy Perry and cats, dogs and horses vie for the most beloved and adorable pet, it’s a wonder to think about how one can and should look at art through the lens of the edited Internet and apps. Taking Berger’s ideas for looking as a starting point, how is the idea of looking changing on the Internet and through smartphone apps? In the age of always on apps and the Internet, is it possible to return to the childlike state of looking?

“Seeing comes before words,” writes Berger. “The child looks and recognizes before it can speak.” Indeed, the Internet is ripe with stories about how children are interacting with iPads and iPhones. Writes PCWorld nearly two years ago, when the first iPad came out: “I think the iPad will spark a revolution in children’s culture…by the time these kids reach middle school, they will have been using multitouch user interfaces almost every day for eight years or more.” The narrative has since expanded, and children are at the center of it.

In looking at art, we at once have to become child-like again – approaching the image with zero preconceived notions, seeing as if we knew nothing. We become blank slates, wiping clean our memories and experiences when at all possible. Does using apps and the Internet amplify or make possible this “for the first time” experience? Not in an adolescent way. Rather, in a childlike way.

Seeing Art through Art Museums, Augmented Reality & Map Apps

The High Museum of Art in Atlanta released an app that offers maps of the art museum, a browsable collection of art at the museum, comments on each work of art from members of the community. And then there is the ability to take a photo of a work you see, which you can then either share to Facebook or Twitter, or discuss it in the community that lives within this tiny app. “So amazing in person!” writes a user named Marykh about Pablo Picasso’s 1928 work of art Girl Before a Mirror. No comments have been posted yet.

Project Paperclip is the first augmented photography exhibition by Portuguese photographer Nuno Serrão. The app provides augmented reality soundscapes to accompany each photograph in the exhibition. Walk up to the image in an actual, physical gallery space and scan the QR code. Doing so triggers some pretty trippy music that, depending on your current state, could take you to an augmented reality of your own. The effect of scanning a QR code with your phone from your computer screen and experiencing the music is a neat hat trick. But take away the QR code gimmick and translate this to a real world art space, and it has the same effect of walking into a darkened gallery show of video or installation art, minus the full physical effect.

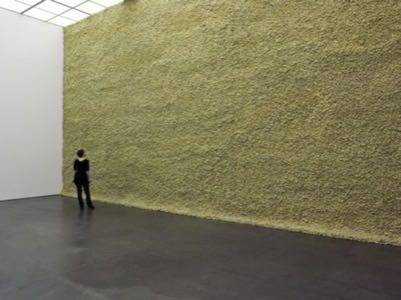

Three years ago the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago presented “Take Your Time: Olafur Eliasson”, a visceral exhibition of sound, light, color and nature. Science met culture, and reverted back to the elements. Eliasson acts more like a scientist, probing the visceral and translating it into a full body experience for the viewer. This is work that demands a full sensory experience. It asks you to take your time – something that technology does not.

Moss Wall (1994) is a simple, elegiac installation of Artic reindeer moss covering a single wall of the gallery. The viewer is left overwhelmed by the fresh, earthy scent of the moss, and as such is transported to another mental space. Imagine yourself as reindeer, brushing up against the brocolli-like nubs of moss, quietly munching on it underneath a sunny sky.

Beauty (1993) is another visceral experience, of stepping into a darkened room quietly inhabited by mist sprays that spit from a hose on the ceiling. Inside a spotlight shines, making a quiet rainbow visible only to the lucky few. We cannot replicate a full-sensory experience through technology, and especially not apps. But at least we can augment our current state of being.

Installation view, Take Your Time: Olafur Eliasson, MCA Chicago

May 1 – September 13, 2009

Photos: Nathan Keay, © MCA Chicago

Project Paperclip proposes a way to augment reality. It takes a highly replicable Internet photograph of nature, combining it with a QR code and sound emitted from an iPhone app. It is subtly disconcerting, an ominous prediction of the artificial realities we build with the help of smartphone apps and the Internet.

When the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York announced Google Goggles for Android and iPhone, the experience of accessing information about art changed dramatically. Now you can go to the Met, take a photo of the work you’re looking at in person, and pull up a database full of information about it.

More recently, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority introduced an app that guides users to 186 permanent works of art that are installed throughout stations in the city, and a few off the Metro North and Long Island Rail Road systems. Public art is indeed now easier to find, especially if you prefer to ask your phone for directions rather than a person or prior Internet research. Or, more importantly, if you prefer the experience as mediated through an app rather than the idea of just stumbling upon something beautiful which may or may not be public art. The app provides information either by subway line or by individual artist.

“In a setting like the subway,” Sandra Bloodworth, the director of MTA Arts for Transit, told the New York Times, “art really does something. It gives a certain amount of dignity to your ride and your day. And this is finally going to be like having the whole collection in the palm of your hand.”

The RedEye Chicago reports that the Windy City is indeed one of the top places for street art. Grafrank.com pulls grafitti photos from Flickr that are tagged “street art” and “graffiti.” It also features artists who tag and have marked the city with their ink that comes from cans.

“The random tagger or etcher on the subway won’t be photographed because most people don’t recognize that graffiti as a form of art,” said New York writer Jake Dobkin, who launched the tracker. “This is more a tool for high quality artists.”

Looking Through the Glass Screen

Smartphones, iPads and social networks provide us with new ways of finding – but they may detract from the actual experience of looking and experiencing in the full-body sense of the word. And even the biggest tech nerds know that.

“So, stuff like this can help educate/self-educate, but it also has the horrible ability to amputate a direct experience of the art,” says writer Curt Hopkins. “I don’t think anyone should ever allow their first encounter with a piece of art to be mediated by so much as a tri-fold brochure, much less augmented reality, if you can help it. It robs you of that moment of pure encounter and limits how you develop your own sensual relationship with art.” To which he adds: “Afterward – or remotely – I think it’s a great resource.”

But as the child continues looking through the glassy screen of smartphones and tablets, the experience of looking at art will evolve.

Images courtesy of Shutterstock and the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago.