Imagine a hospital that could respond to medical emergencies armed with real-time information about exactly where all its doctors were located. Inside the hospital, which cardio specialist is closest to the 4th floor? Outside the hospital – if an on-call physician is racing to get to a patient’s side, how far away are they and when can they be expected to arrive?

From emergency to non-emergency to everyday preventative health care, location tracking technologies could make a big impact on our health and well-being in the future. While two million consumers use Foursquare today to find the best nearby coffee shops and bars, what if in the future they used it to locate the best pediatricians, emergency clinics, or even restaurants that catered to their unique health needs? Some intersection between location and health care has already begun, but what we’ve seen so far is likely only the beginning.

I showed my dental hygienist who else was checked-in there on Foursquare last time I went to the dentist’s office and she was quite taken aback. But we consumers willingly shared our presence at and feedback about that medical facility. That’s only the beginning of what’s likely to happen.

If health insurance agencies track your location and charge you more for insurance, you’re probably not going to appreciate that. There are some possible upsides to the intersection of location and health care, however.

For the Patient

“I would love to see HospitalCompare and Health and Human Services (HHS) data mashed up with mobile location apps for health care consumers,” says Brian Ahier, Health IT Evangelist at Mid Columbia Medical Center in the Dalles, Oregon. “Helping me find the best pediatrican or orthopedic surgeon would be a great application. And once I’m there, I want to lodge a positive or negative complaint on the same service.”

“This is all about the patient,” argues Mark Scrimshire, founder of the HealthCamp movement of healthcare unconferences around the world and an employee at a large healthcare payment corporation in the US.

“The one person who is not by their computer during a medical transaction is the patient. They are in the hospital or in the pharmacy. As smartphones take off, there will be tremendous potential for really supplementing the patient and bringing them data that’s relevant. Location services could recognize that you are going into a pharmacy, for example, and remind you what your prescriptions are and of anything you needed to talk to your pharmacist about regarding those prescriptions.

“When you walk into the doctor’s office, your smartphone should configure your data and prompt you to transmit your health measurements from home quickly and easily, because it knows where you are. I think there’s a lot of potential for augmentation of the patient to let them monitor their own health. That will happen through a wide variety of sensors and location is one important factor that will provide context for that sensor data. ‘Blood pressure up? Well, he was at work again.'”

Scrimshire also sees location data being served up to Augmented Reality style apps to help patients navigate their way through the maze-like halls of big hospitals – and providing the kind of in-home tracking that would help the elderly stay in place, instead of being institutionalized.

“Putting a few thousand dollars of monitoring equipment into a home, if it prevents someone from visiting an emergency room, it pays for itself with the avoidance of one visit,” he argues.

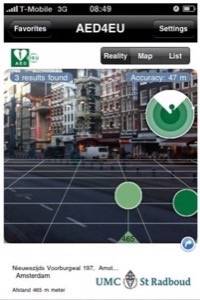

These kinds of strategies may be less far-fetched than they seem. Medical providers are already offering Google Maps of the best facilities to seek appropriate care. A University Medical Center in Holland has even built an emergency Augmented Reality display that allows you to look through your mobile phone’s camera view and locate the nearest automatic external defibrillators (AEDs) located in a public place.

For the Doctor

There are already systems in place in many hospitals to track medical equipment, but what about tracking the medical professionals themselves?

Brian Ahier works in the same small Oregon town where Google recently built a big data center, The Dalles. Earlier this year Google gave the town a grant to build a free city-wide wifi network. Wifi is just one of several ways that the locations of mobile devices can be tracked.

“If there’s an emergency and we need to call up all hands on deck, it would be really handy to be able to pull up a map and see where everyone is,” Ahier says. “It would need to be secure, and probably for people who are on call only. It would have to be an opt-in situation by the physician.”

Inside the hospital, location data could prove very useful in tracking updates from devices located in various parts of the institution as well.

“At some of the HealthCamps there have been conversations about secure Twitter-like conversations in a hospital environment, even between devices,” Mark Scrimshire says.

“Imagine if every bed and device could send and recieve Twitter-like messages. Imagine if you come onto duty and you get the feed of all the updates from all the patients and devices.

“Because of the life or death nature of the industry, it doesn’t move that quickly and thus hasn’t adopted technology like this. ‘Meaningful use’ in healthcare right now is about whole-record interoperability, this would be about real-time mashing together of data feeds from different devices and building filters and context. If a patient has a device on them, where are they and how does that relate to other things you’re tracking? That makes for better management of the patient. Is a health care provider doing something out of sequence? Location becomes a factor that helps to add context to all these things we could monitor.”

Obstacles to the Vision

Some location technologies will likely impact health care sooner than others. There are obstacles to the kind of future that Ahier and Scrimshire describe. Ahier, for example, says that GPS signals on phones vary too much in accuracy today. And the iPhone is too proprietary for many corporations to build on top of. “Almost all the doctors have iPhones, too,” he says. “Even if we give them BlackBerries, they go out and buy their own iPhones.”

“Ultimately, I think we’re going to need to be platform independent, even device independent,” Ahier argues. “We’re going to need to be able to use an Ubuntu netbook, an iPad, etc. Our EHR (electronic health records) are going to have to run on all those.”

Scrimshire believes that location technology providers in healthcare will go Google’s route and build HTML5 mobile web apps, which nearly every smartphone on the market will soon support.

Scrimshire believes that the bigger issues are cultural. “The whole industry is very conservative because of privacy,” he says.

“HIPAA [the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996] is used as an excuse not to share, but the P is for portability. The big trap door is that we as patients can demand our data, people may want to charge us for us, but our information is our currency. We can decide when and with whom we want to share it.

“Security is going to be the issue the industry is going to through up as an excuse to not do anything. It’s been a minefield to get quality data published about doctors and hospitals, it’s a minefield to go through. The healthcare industry is still one where there’s a lot of advantage to a lack of transparency. You don’t realize you could save $200 by going down the road for the same treatment because the information isn’t available.

“But some trends are coming together, in part because of the recession. Employers are putting more of the responsibility for paying for health care on the shoulders of employees, through high-deductible insurance plans, for example. When they start feeling the cost more, then they start asking questions and asking if there are other steps they can take. When the onus is put on the consumer, you’ll see them demand a change in the healthcare industry. The consumer can demand their information and be more on par with the physician and make decisions. Then you’ll start to see the innovators really coming into the picture.”

Will location data be a major disruption of the balance of power between the various stakeholders in the healthcare industry? Will it make shopping for health services, or staying healthy, an easier casual activity for more and more people with smartphones?

Will doctors and medical devices be instrumented, tracked, analyzed and more effectively managed to reduce cost and improve the quality of care?

These visions of location-based health care may be a ways off, but they could also be fast approaching. Just today the FCC and the FDA signed an agreement to jointly develop technical standards for wireless-enabled medical devices and services. Location technology and healthcare could come together sooner than we might expect.