Barack Obama is on Instagram. He’s on Foursquare and Facebook, too. He’s even on Google+. On Election Day, he suggested that his pioneering Web presence wouldn’t end with the campaign, but would continue into governance. The new administration would foster innovative engagement, and Obama would become our first wired president. But does buying promoted tweets and having fewer “likes” than Vin Diesel and Adam Sandler inspire anything resembling citizenship 2.0? As Jon Stewart has observed, much of Obama’s Web presence today is merely asking for money.

Guest author Hamza Shaban writes on Web culture and technology at DrapersDen.wordpress.com. He graduated from the University of Virginia.

Consider the hysteria surrounding SOPA and PIPA. These bills were drafted to protect intellectual property

. If signed into law, the Department of Justice would be granted broad powers to block foreign websites that violate copyrights. American ISPs, search engines and advertisers would all be adversely affected. The backlash was frenzied.

On January 18, 75,000 websites took part in a coordinated strike to protest the bills. 162 million people viewed Wikipedia’s blackout page. 350,000 emails flooded Congress through SopaStrike.com and AmericanCensorship.org. Dozens of Representatives and Senators came out against the legislation – including, embarrassingly, three sponsors of the bills. Days later, SOPA was pulled. #EpicFail for @Congress.

It’s hard to dispute the startling efficacy of anti-SOPA outreach, and the outsize influence of individuals who have grown up on the Web. By having a clear, tangible objective (Killing SOPA) and a coordinated action plan (Blackout Wednesday), online protesters converted social unease (No more Reddit? WTF) into political engagement (bombarding elected officials).

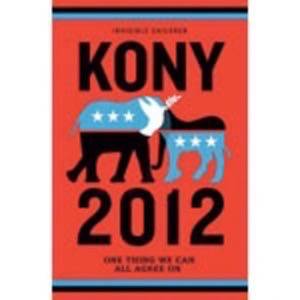

The creators of KONY 2012, the most viral video ever, are also following this model of digital-to-actual netroots activism. Unlike SOPA, which had Web juggernauts (Google, Wikipedia, Facebook) and the entire tech industry involved, KONY 2012 grabbed eyeballs with a gripping video. The campaign’s goal is to have Joseph Kony, international war criminal, abductor and murderer of children, brought to justice by December 2012. At the end of March, the original YouTube video had over 86 million views.

Engineered to spread – visceral and disturbing, passionate and provoking – KONY 2012 is the rare documentary that stirs more than it saddens. (After watching “No End in Sight,” or “Inside Job,” the overriding emotion is despair. Neither film offers solutions.)

Where most commercials for politicians are clueless self-parodies – depicting the world as either impossibly optimistic, when they are about themselves, or frighteningly apocalyptic, when they are about the out-of-touch opponent, KONY 2012 instead takes its viewers seriously.

Since the video was released, both the House and Senate introduced resolutions in support of disarming Kony’s militia, the LRA; and the African Union’s Security Council has deployed 5,000 soldiers to track Kony down.

KONY 2012’s next step, “Cover the Night,” encourages activists to plaster their cities with campaign posters today. (Imagine waking and finding your entire neighborhood covered by peculiar ads.) By raising awareness of Kony’s brutality, it is believed more American political leaders will be pressured to take action. “Cover the Night” will be a telling experience. Since it requires activists to do more than type and click, a strong turnout will prove the campaign to be more than a trending meme.

Building a digital campaign around a compelling narrative has also drawn critics to KONY 2012. Many argue that the campaign oversimplifies the issue, that its slick appeal exploits the plight of Africans. Take Angelo Izama’s essay, “Kony Is Not the Problem,” in The New York Times: “Campaigns like ‘Kony 2012’ aspire to frame the debate about these criminals and inspire action to stop them. Instead, they simply conscript our outrage to advance a specific political agenda – in this case, increased military action.”

Similar to the debate around SOPA, it seems that dramatizing a political issue, framing the conversation for the general public, also risks diluting its nuance. However, to interpret KONY 2012 as a misguided attempt to manipulate is too harsh.

Everywhere, in books and film, magazines and television, we are told of our country’s enduring problems: inequality of women and gays, the education gap, climate change, military overspending, etc. The issue isn’t a lack of intellectual discussion, but rather the sheer absence of political engagement. It’s not that we do not know; it’s that we do not care – or too few care enough to act.

If advocates abstain from popular storytelling, from employing emotion to persuade, how else do you rouse a population to participate? If sports teams, consumer products and movies inspire so much loyalty, why not borrow some of their marketing techniques for politics – where the stakes and payoffs are so much higher?

Stephen Colbert understands this. Originally titled “Hail to the Cheese Stephen Colbert’s Nacho Cheese Doritos 2008 Presidential Campaign,” the comedian-candidate illustrated the onerous requirements for grassroots politicians.

Later in 2010, he testified in front of Congress to draw attention to our jingoistic stance on migrant farm workers. In full character, Colbert captures the hypocrisy of our immigration laws ill-suited for a globalized economy: “America’s farms are presently far too dependent on immigrant labor to pick our fruits and vegetables… I don’t want a tomato picked by a Mexican. I want it picked by an American, then sliced by a Guatemalan and served by a Venezuelan in a spa where a Chilean gives me a Brazilian.”

When was the last time you watched a congressional hearing… about anything?

Colbert also brings much-needed criticism to the insidious and ubiquitous role of campaign fundraising. By promoting his own super PAC, “Americans for a Better Tomorrow, Tomorrow,” Colbert mocks as he teaches: PACs can accept unlimited amounts of money from individuals, are generally used to fund negative ads, and are usually connected with candidates (which is illegal but easy to evade). No cultural icon is engaging the public in this playfully creative way. Nor has any public figure bothered to provoke young Americans to tangle with the Federal Election Committee.

Nobody is arguing that digital petitions, viral videos and late-night TV will lead to American regime change. Twitter didn’t topple tyrants – protestors did. The Arab Spring wasn’t started by a tweet, but by a Tunisian – who set the desert on fire by using his flesh as kindling.

The social Web isn’t the revolution, but a tool for revolutionaries. As Occupy Wall Street demonstrates, tech-savvy anger without a unified, actionable agenda is just noise. (OWS could make a convincing case for specific electoral reform – dismantling the winner-take all Electoral College, creating publicly funded campaigns or standardizing fair ballot access for third parties).

While other areas of our culture are blazing with tech innovation, our modes of political activity remain stagnant. As Sean Parker, Napster founder and former President of Facebook, has noted, “Politics is one of the few remaining large-scale consumer-facing opportunities on the Internet … It’s a very interesting moment, where politics is a bit behind the rest of the economy in embracing these new technologies.”

Putting his money where his mouth is, Parker founded the startup company Causes and has also invested in Nation Builder – both social platforms that rally like-minded individuals through activism and philanthropy.

Another Parker-backed venture, Votizen enables activists to create coalitions based on public voting records. By combining the digital ties of social networks with actual political activity, Votizen hopes to lessen the influence of money and bolster voter-to-voter engagement.

Where political institutions have failed to harness our discontent, this kind of technology has daring promise. As the digital protests surrounding SOPA, KONY 2012 and Stephen Colbert suggest, our underlying concern needs only to be sparked.

Lead photo courtesy of Flickr/jackmcgo210.