The Project Wing delivery drone Google revealed to the world last August is no more. Instead of going head to head with Amazon’s drone initiative, the Google X team behind the UAV (unmanned aerial vehicle) decided to scrap its plans and pursue a different design.

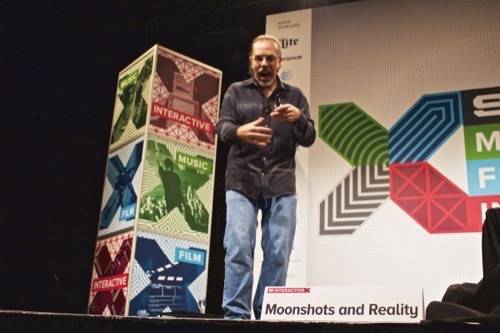

Google’s “Captain of Moonshots” Astro Teller, who leads its secretive X lab, revealed to a South By Southwest crowd Tuesday how the decision came about. It began with CEO Larry Page giving his team a tough mission: He wanted a prototype that could deliver goods to non-Google employees within 5 months. Teller and his crew only had one design that they could build that quickly, and even though they knew it wouldn’t be right, they went ahead with it anyway.

See also: Google Challenges Amazon’s Drone Delivery Program With Project Wing

It might sound odd to proceed with a project that was destined to fail, but Teller considers failure an integral part of the process at Google X. In fact, he says it’s a key ingredient for success.

Taking Wing

At Page’s behest, the team continued work on the doomed Project Wing delivery drone for 5 months. Once the term was up, the team had a clearer vantage point of the work at hand. They abandoned the version that debuted last year and began work on a totally new design that reflects everything learned from that previous experience. (Google X promises to say more about the new drone’s design later this year.)

Project Wing isn’t the only failure Teller wants the world to know about. Another recent, and much publicized, example is Google Glass, the smart eyewear Google sold to a group of “explorers.” The company later abandoned its original plans before the facegear could reach the general public. Though not quite dead, the device is no longer a Google X project. It will live out its second act under the umbrella of Nest co-founder and recent Google addition Tony Fadell.

“The thing that we did not do well, that was closer to a failure,” Teller said, “was that we allowed and sometimes even encouraged too much attention for the program.” In other words, instead of clearly classifying the product as an early prototype, the company practically hyped and marketed it as a finished product. That was at odds with the whole point of the Explorer program, which essentially placed the headsets with beta testers.

Keeping Failure—And Success—Afloat

While Glass got a lot of high-pressure, high-profile attention, many of Google X’s failures are small. In those cases, they can work like the essential baby steps that can refine a product while research and development are in motion.

See also: Google Glass Moves On From Google X, Lands In Tony Fadell’s Nest

For instance, Google managed to improve its Project Loon initiative, which aims to provide Internet to remote parts of the world, by increasing the life of the balloons. The company figured out how to keep them aloft longer, going from just a few days or even hours, to as long as six months—a feat previously thought of as impossible—by testing, testing and then doing more (you guessed it) testing.

At first, Google couldn’t figure out why its balloons were springing leaks at high altitudes. So it brought them to North Dakota during the polar vortex and saw what happened in the cold. It would make a small tweak to a balloon, fly it at the same time as another with the older design, and then measure the difference. The company even tested how thick its balloon technicians’ socks should be to prevent damage to the surface.

“It was worth it in order to teach the balloons how to sail,” said Teller. “There was no way, except feeling it out and getting that experience.”

Teller thinks any business can adopt the same strategy. He encourages workplaces to have many different minds working on many different problems, to benefit from the diversity, and to ensure every failure comes from a calculated risk that can teach something. He said he is always open to failure from his team, and that means not necessarily expecting success. Instead, he recommends failing early and often, which will cost companies less than failing in the end.

Project Loon photo courtesy of Google; all other photos by Owen Thomas for ReadWrite.