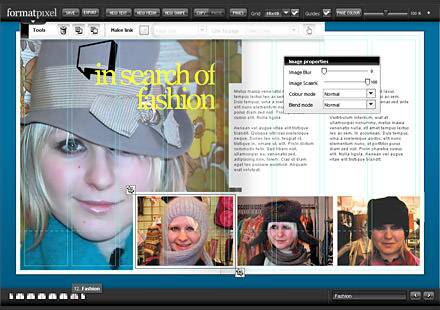

The world of webtop publishing (WTP) has come on in leaps and bounds in the last few years, with plenty of services feeling as good, if not better, than many standard desktop packages. This is particularly true in the case of Microsoft Word-alikes such as Google Docs (née Writely), ThinkFree and Zoho Writer, which were featured in Josh Catone’s excellent Self-Publishing Toolkit post earlier this week. In this post we’ll take a look at one stand-out service on the more visual end of the market – an online tool aimed at those who are familiar with the ‘print’ world’s standards such as Quark Express or Adobe InDesign. The service is FormatPixel, a Flash-based app that mimics the functionality of a desktop publishing app for the purpose of creating a visually stunning brochure web site without the need to break the bank.

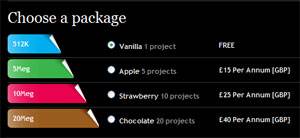

FormatPixel has a thankfully simple registration process to endure before you can start playing around with your first project. You’ll need to choose which payment scheme to use. We chose the ‘Vanilla’ – or entry-level – scheme. This is free, but limits your account to just one project, and doesn’t allow you to export your projects as Flash files. On the plus side, whereas the starter version of other popular “freemium” apps, such as Basecamp, limit functionality on the entry level plan,the Vanilla level of this service includes access to every feature apart from the aforementioned export. There are three other packages to choose from, with the priciest (‘Chocolate’) allowing the user to make 20 projects for $US80 a year.

We also opted to use the Beta version of the publishing application for this review, rather than the supposedly more stable version, because it included some extra animation features along with the standard feature set detailed below. We didn’t run into any issues with stability or flakiness in the Beta version, however, so we’d expect the standard, non-animating version to be just as slick.

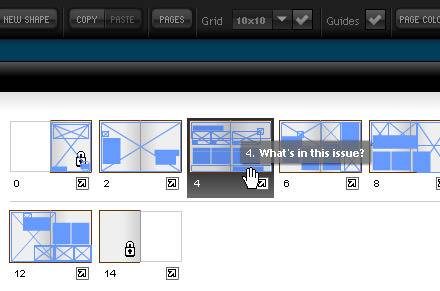

Because it’s not pretending to be a whistles-and-bells publishing tool, it’s easier to create content right away with FormatPixel than learning the intricacies of a traditional layout program like Quark. Each of your projects is organized with thumbnails of the pages below the main editor frame, so navigation from one page to the next is straightforward. Once you’ve started drawing shapes on your pages, outlines of those shapes appear in the thumbnails, to aid your memory of what’s where (see picture below). You can select the dimensions of your backdrop too, should you want your project to look more like a widget or a blog than a standard magazine spread. Tracking guides have been added to help you keep consistent layouts from page to page, but unfortunately, the shapes and other object don’t ‘snap’ to the guides as you would expect in a full-featured app.

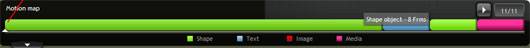

Creating new shapes and text blocks is a one-click affair; editing those elements requires a double-click. Once you’re in edit mode, you can adjust colors with a handy RGB slider, and set some text and shape preferences such as outline and blend options. If you’re using the Beta version, those shapes (and other media) can have basic animation behaviors assigned to them, such as fades and slides. The animation is ‘playable’ via a timeline at the foot of the canvas that shows the actions in frames, a la Flash’s own timeline. Don’t expect Photoshop-like finesse of shapes and images, but for the purpose of presenting a decent online scrapbook, it’s more than adequate. One serious drawback though is the inability of the text blocks to accept images or other media themselves (meaning text would flow around the media). Also, forget about applying two or more columns of text to a block; you’ll have to settle with appending one block next to another. That said, we were impressed with just how streamlined and intuitive the interface was; it’s just a shame that for a layout tool, more thought didn’t go in to some of the quirks surrounding text blocks.

Probably FormatPixel’s most useful service is the ability to add links from shapes to either external URLs or different pages in your project. This makes creating clickable wireframes a snap. Anyone thinking that this tool could be used for early-stage prototyping, you’re right. (For the purposes of this review, I played around with the tool with exactly this intention – rapid development of a simple site design – and found it easier and quicker at the task than my typical wireframing tool, Microsoft Visio.) Finally, there’s your personal library of photo or Flash video media. You can import, crop and tag your photos and vids, or paste in a YouTube URL for FormatPixel to add the video to your library. Then it’s simply a matter of dragging your media to the right place on the canvas.

Once you’re happy with your project, you can publish it (or keep it private) to the growing directory of current galleries, comment on other folks’ work, and find out how many people have viewed your projects. You’re assigned a profile page too which lists your work and stats. And, as we mentioned earlier, paid users can export their projects as Flash files that they could insert in any site or presentation as Flash objects.

Conclusion

None of FormatPixel’s features will take your breath away (for that, we’re waiting to see what birds of paradise emerge from the Aviary); but what FormatPixel does, it does well, and does simply. The community is young, and in need of some sharp projects to act as showcases, but we can already see this starting to bloom, especially if FormatPixel offers a few more carrots to the most creative users, as well as beefs up the app’s feature set a bit. Photographers or graphic artists looking to publish their wares online in a stylish and interactive format will need to search hard to find a better alternative to FormatPixel.

What are your thoughts about FormatPixel? Know of a WTP product that blows this one out the water? Let us know in the comments.