Can you name an influential woman in computer science?

If you’re well-versed in your history, you might think of 19th-century mathematician and programmer Ada Lovelace. Or, more recently, computer scientist Grace Hopper, who coined the term “debugging.”

Two women across two centuries makes for a scant supply of role models. There are more—many more. And some women are working to make sure future generations of programmers will know their names.

Meet The Computers

Men and women together created the first all-electronic, programmable computer called ENIAC. Men developed the hardware, and six brilliant, long-forgotten women built the software.

Kathy Kleiman, founder of the ENIAC Programmers Project and creator of the short documentary The Computers, discovered these women as a young programmer herself in the mid-1980s.

While researching a college project, Kleiman found a photo of the ENIAC computer surrounded by women. The men in the photo were identified in a caption but the women were not. A representative of the Computer History Museum told Kleiman that the women were models.

They were not. They were women known as “computers,” and they’d been selected to program a machine that could do their wartime work of calculating ballistic trajectories.

“Historians covered computing as a story of hardware,” Kleiman told me in an interview. “We’re actually going back to uncover the names and the work, because programming was a pink-collar profession for about the first decade. There were some men, but it was actually hugely women.”

The ENIAC was created as a secret military project during World War II in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. At the time, no technology like it existed, and when it was unveiled to the public after the war in 1946, people called it an “electronic brain.”

The hardware itself was difficult to understand, and the software even more so. Instead of introducing the hardworking human computers who had given the machine its brains, the Army gave credit to the two men who built the hardware—John Mauchly and J. Presper Eckert. The women’s roles were forgotten—until Kleiman found their names.

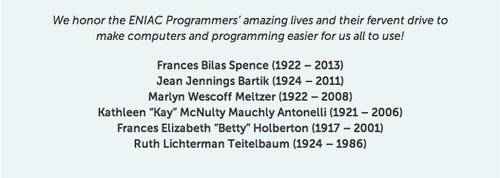

Frances Bilas Spence.

Jean Jennings Bartik.

Marlyn Wescoff Meltzer.

Kathleen McNulty Mauchly Auntonelli.

Frances Elizabeth Holberton.

Ruth Lichterman Teitelbaum.

Kleiman’s ENIAC Programmers Project aims to bring women into the spotlight who have remained invisible for so long—not just the six women who helped create the ENIAC, but female computer scientists throughout history.

Her motivation isn’t just correcting the record of the past. It’s building a future that looks different from a history that’s been airbrushed to look more male than it really was.

“If our initial pioneers are invisible, then our later role models are lost,” Kleiman said.

The Computers is the first in a three-part documentary series about women who have been forgotten in technology. The next two parts, The Coders and The Future-Maker, will focus on female programmers who helped create Java and Flash.

Megan Smith, the Google executive recently named as chief technology officer of the United States president at, wrote about the invisibility of women in technology in an essay on the Huffington Post:

In the Steve Jobs movie, we barely meet Joanna Hoffman and we don’t meet Susan Kare, both were a core part of the original Macintosh product development team. Their contributions literally changed the face of the Mac and our industry. In the Turing films, we don’t meet the many mathematical women who made up half of the code-breakers at Bletchley Park during WWII.

Hollywood could do more research when producing these movies—but the silver screen is often a distorted mirror. It reflects people’s assumptions and the media they’re exposed to. If women are scrubbed from history, they likely won’t find their way into film. That’s just one thing Kleiman is working to change.

Seeing The Present

While Kleiman works to correct our understanding of computing’s past, others are trying to expose people to female role models working in the field today.

Julie Flapan, executive director at the Alliance for California Computing Education for Students and Schools, is working on boosting computer-science education for primary and secondary students, especially young girls and students of color. She says one important way for young, diverse students to understand that computing can be a career for them is by meeting computer scientists who break the white-male stereotype, and learning from them.

“Not many girls and people of color see themselves represented as a computer scientist,” Flapan said in an interview. Without that, she said, students may question whether or not computer science is a field for them.

Telle Whitney, president and CEO of the Anita Borg Institute, says that having role models is important for career development, and is an inspiration for women who might consider a different university of career path.

“If you don’t see anyone who looks like you, it’s harder to imagine yourself in that role,” Whitney told me in an interview.

In an effort to provide those personal resources to women in technology, both those starting their career path at colleges and universities and professional women already in the workforce, the Anita Borg Institute produces the annual Grace Hopper Celebration, the world’s largest gathering of female technologists.

Some universities send their students to the event to connect with women who will one day be their peers or supervisors should they choose to continue their careers in computer science.

Harvey Mudd College, a liberal-arts school near Los Angeles, sends freshman students every year. This year, the college is sending 52 students and 5 faculty members to the event.

Colleen Lewis, assistant professor of computer science at Harvey Mudd College, is attending this year. She personally understands the impact that meeting people like themselves can have on students.

At Harvey Mudd, 40% of students enrolled in the computer science program are women, thanks in part to efforts by the college to make the program more welcoming. But for many students who aren’t exposed to female peers and faculty, events like the Grace Hopper Celebration that put women front and center can give students role models they wouldn’t find anywhere else.

“When I was an undergrad, I went to the Richard Tapia Conference,” Lewis said in an interview, referring to a biennial conference on diversity in computing held in Boston. “Coming from Berkeley, where there were between 11-13% women in my major, it was very impactful.”

Where the efforts of people like Kleiman and Whitney come together is teaching women pursuing degrees in computer science that they’re not alone. That they never were alone. That they’re not even among the first of their gender to forge a path in a male-dominated industry. And that if others did it in the 1940s, they can do it, too.

“My goal is to share the history, so that no girl ever thinks there weren’t women in computing,” Kleiman said. “Can you imagine a world where there were no stereotypes at all? Where everyone knows that women and men created computing together, and that everyone know she or he has the right to go into these fields? To me, that would be a great place for the world to be.”

Lead image courtesy of the University of Pennsylvania Digital Archives